Jul 8, 2015 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality, Email Newsletter Full Article

One of the great challenges of spiritual practice is not to confuse the form with the purpose. For example, when first learning to meditate, it is easy to assume that the practice is about noticing breath (or whatever the object of focus is) and that to be “successful” in meditation, you have to be able to sustain long, undistracted attention to the breath. But as we deepen the practice, it becomes clear that it is not actually about the breath at all. It is about many things: learning to live life with intentionality, noticing conditioning of all kinds, listening to the wisdom of the body, refining compassion and humility, cultivating dedication and concentration, just as a start. But it’s not really about the breath.

And yet, it actually is crucial to start with the breath. The breath is the form, the container through which these other benefits emerge. By using the structure of bringing attention to the breath, we can see more clearly what actually arises and experiment wisely with that. Occasionally we may be able to do this kind of work spontaneously without the form; sometimes the muse does strike us. But as spiritual practitioners (and good writers) know, more often than not, spontaneous wisdom and insight is a rare gift.

The same is true in prayer. Too often in the Jewish world we focus on mastering the form: the Hebrew, when to bow, sit or stand, all those words. In the world of Jewish prayer, it gets even more complicated, because, in fact, there isn’t just one form. We can work with the matbe’a (words of the prayer book), blessings, chanting, or hitbodedut (talking out loud to God)—each its own form to master. But in all cases, as we deepen our prayer practice, it becomes clear that it is actually not about the form. Just like in meditation, the form is the structure through which different kinds of experiences and experimentation can happen. Perhaps it is about opening the heart to God. Perhaps it is about opening the heart at all. Perhaps it is about cultivating gratitude and wonder or going deep into the unknown.

One way to differentiate between the form and purpose of spiritual practice is to practice with intention: Why am I doing this practice? What am I hoping or aiming for? Asking these question helps keep the form fresh. It infuses the form with possibility, with creativity, with aliveness. It is one of the things that can help make practice not rote, but transformational.

Mar 2, 2015 | Email Newsletter Full Article

By Rabbi Marc Margolius

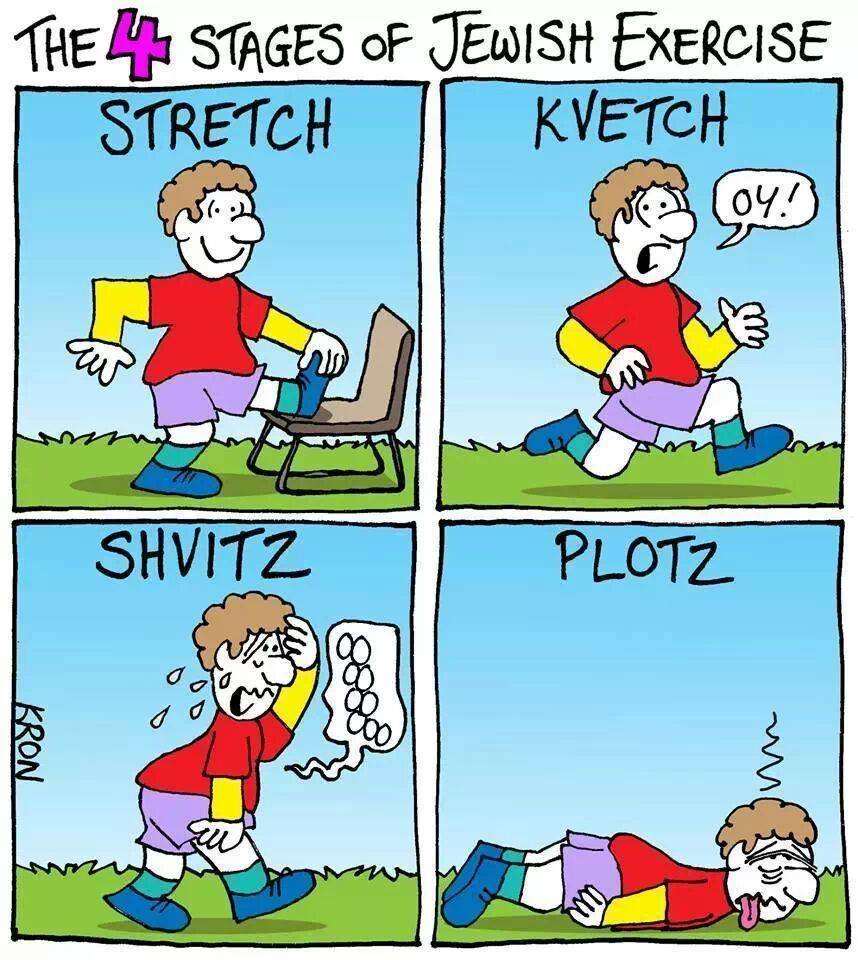

The Institute’s Tikkun Middot Project integrates mindfulness practice with attention to a series of middot (spiritual/ethical qualities). This month, we are focusing on another essential Jewish spiritual trait as our middah of the month. Below you will find wonderful resources for meditation, embodied practice, and text study of the middah of kvetchitude.

Meditation of the Month: “Eh. Things could be better.” (The Veyizmir Rebbe)

Guided meditation: Close your eyes. Visualize any number of ways in which life could be better.

Embodied Practice of the Month:

Scrunch up your face tightly. Shrug your shoulders. Release. Sigh deeply. Moan. Whine. Repeat.

Text study:

And Adam kvetchethed to Eve: “For sure, we can eat anything. The weather is great. And the fruit is always in season. But would it spoileth some divine plan if we ate an apple, for God’s sake?”

(Bereishit Rabbah, midrash on Genesis 1.)

The people took to kvetching bitterly, saying “Oy” and “Vey iz mir.”

“Behold,” said Moshe to the Holy One, “they truly annoyeth me.”

(The Book of Numbers, ad nauseum. Also, see pretty much the whole Torah.)

“Hath we arrived there yet?”

“You calleth this a meal?”

“What? No Evian? Alright, alright. I guess tap water will do.”

“So, whence cometh the brisket?”

“One would thinketh the towels could be thicker, no?”

(Selections from Bamidbar Rabbah, midrash on Book of Numbers.)

Ben Zoma said: Who is wise? One who learns from everyone.

Who is mighty? One who subdues one’s passions.

Who is rich? One who rejoices in one’s portion.

Who is honored? One who honors one’s fellow human beings.

Who is miserable? One who wins the lottery and kvetches that last week’s pot was bigger.

Others say, one who complains loudest that the bagels were gone by the time he (some say she) reaches the buffet. (Others versions: the lox, not the bagels.)

Some say, who is miserable?

One who just moved one’s car and forgot that alternate side parking hath been suspended (this view is observed only in New York City and walled cities).

(Mishnah Avot – Ethics of the Patriarchy 1:4, version discovered stuck in a menu at the 2nd Avenue Deli.)

Note: this post is a joke, in the spirit of Purim!

For more information on the Institute’s Tikkun Middot Project, click here.

Oct 15, 2014 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality, Email Newsletter Full Article

For the third time in a row, I got to spend Yom Kippur and the first part of Sukkot in Israel. For Yom Kippur, I went to one of my favorite synagogues in Jerusalem where the liturgy is traditional and the singing is joyful and powerful. For me Yom Kippur is such a day of supplication. It felt particularly fitting this year to spend it praying and singing and weeping in Jerusalem.

This year I noticed a feature of the liturgy that I hadn’t paid much attention to before. Towards the end of the Kol Nidre service, the traditional prayer book goes through a recitation of the Thirteen Attributes of God four times. These thirteen attributes remind us that God is merciful and gracious, patient, compassionate and forgiving. And then at the end of the day, in the middle of Neilah, after all the prayers and poems and recitation of sins, we return to the Thirteen Attributes, not four times, but a whopping seven times.

Now, it makes sense to me that we would begin the process of Yom Kippur with an emphasis on Divine compassion and mercy. This makes it safe for us to enter into this difficult day of truth telling, remorse and pleading. We trust that our words will be heard with love. But why do we conclude the day the same way?

It occurred to me that although we spend (or at least can spend) much of the day looking into the spiritual mirror, Yom Kippur itself is not always a day of actual inner change. In fact, I would say that it rarely is such a day. When darkness falls and we get up to resume our regular lives, we may have gained greater insight into our habits of heart and mind, but without ongoing practice, it is difficult to translate that insight into real sustainable change.

Perhaps that is why one tradition is that we are not truly, truly sealed into the Book of Life until Hoshanah Rabbah, the seventh day of Sukkot. We may conclude Yom Kippur feeling exhilarated, cleansed, redeemed, but there is more work to do. So we need those extra reminders of God’s merciful attributes. In fact, we need a full cycle of seven repetitions of them to encourage us to make the difficult on-going commitment to the spiritual practices that will help integrate our new intentions into our lived lives.

As we come to the conclusion of our yearly cycle and begin the new one, may we feel upheld by compassion, patience and grace so that we can take up the transformational work of a new year. Chag sameach!

Sep 23, 2014 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality, Email Newsletter Full Article

In some ways, it is a pity that Rosh Hashanah doesn’t fall on Shabbat this year. We are going to have to listen to the shofar.

Of course, listening to the shofar blasts is one of those visceral experiences that tell us, yes, the High Holy Days have arrived. It is like hearing Avinu Malkeinu with that familiar melody or tasting apples in honey: those quintessential Rosh Hashanah experiences in the body that simultaneously ground us in this moment and bind us to other Jews in other places and times.

Traditionally, observant Jews don’t sound the shofar (or recite Avinu Malkeinu) on Shabbat. This year, Rosh Hashanah falls on Thursday and Friday. But in some ways, this is the year for the shofar to fall still so that we can listen more deeply, with greater focus.

For many of us, this was a difficult summer. Menachem Nachum of Chernobyl, the Me’or Eynayim, noted that suffering often has the result of narrowing our awareness, so that we become more focused on our suffering. It can become quite a nasty cycle.

Listening, really listening, is one of the things that can help take us out of that cycle. Listening takes us out of ourselves and into connection with others. But sometimes it can be confusing. We may listen for what is new or unknown. Or we may “listen” for a particular agenda, to the stories that reinforce what we think we already know. Unfortunately, that often leads us back to the cycle of suffering.

The shofar will be sounded this year in all the places Jews gather; listening to it has the potential to take us out of ourselves and into connection with others. But often we think we know what we will hear. What if instead, we listened as if we had never heard the shofar before? What if we listened for the echo of the shofar in our own hearts? What if we followed a recent teaching by Norman Fischer and listened to the silence from which the blasts emerge and to which they return? How might that inspire us, comfort us, sustain us in this upcoming year?

May the practice of listening – to the shofar, to the suffering of others, to our own hearts – help us bring an abundance of blessings to our world in the New Year! Shanah tovah!

PS: Speaking of abundance, check out our Shmita blog! And if you are interested in learning more about the Me’or Eynayim, sign up for our text study!

Jul 15, 2014 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality, Email Newsletter Full Article

The other day I had coffee with a friend after work. We both were in a state of anguish about the violence in Israel and Palestine. She confessed that she was feeling despair; how could things ever get better? What could possibly be the catalyst for real change?

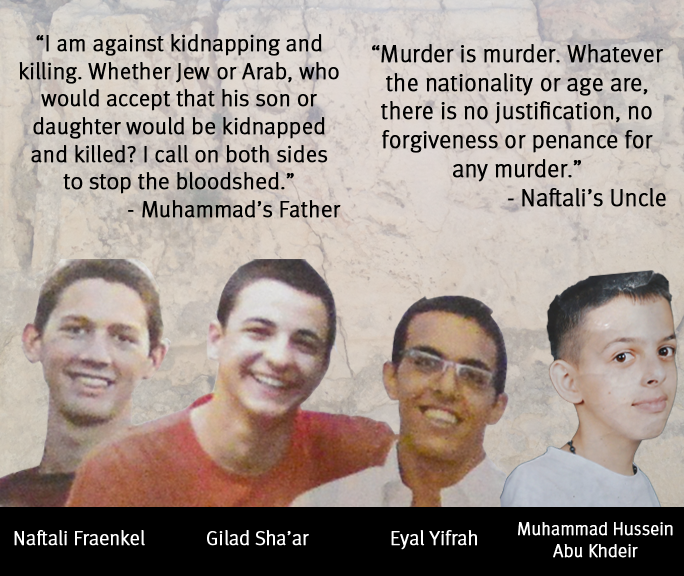

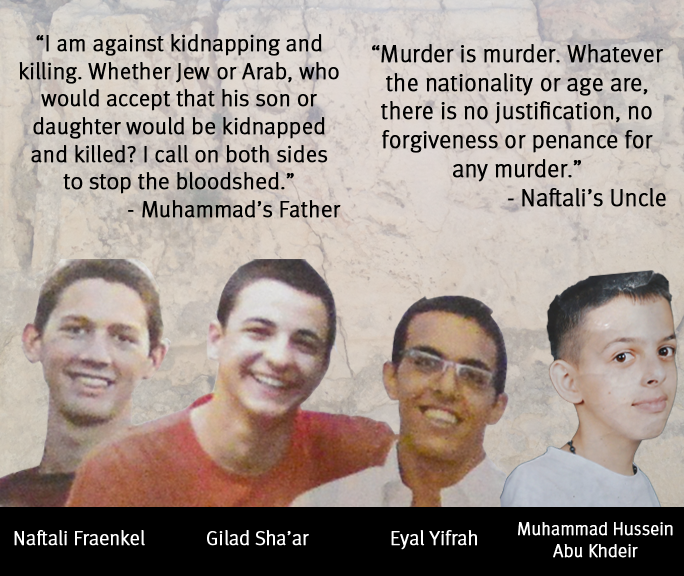

I thought about all the postings I see on social media. Ever since we learned of the murder of Naftali, Gilad and Eyal, and then the murder of Muhammed, and then the rockets and bombings, so much of the rhetoric has been justifying one side or the other or expressions of hopelessness. I feel the impact it has on my heart: I feel defended, closed, self-righteous. I experience how anger leads to more anger, despair to more despair. I feel my heart hardening into accepting the status quo cycles of violence and hatred as inevitable.

But it could be different.

How? I am so far away and so small. I am not naïve enough to think I can have any impact on Hamas or Netanyahu or anyone else who has power and weapons. And I am also not naïve enough to think that I am completely powerless.

If I want more hope, I have to add hope back into the system. If I want more openness to peace, I have to work on examples of openness to peace. If I want a vision of what could be possible in the turbulent land that I love with a full heart, then I have to speak out and encourage others to do the same.

A small example: Zena Schulman, our Communications and Development Associate, created an image last week of the four murdered boys along with quotes from their family members denouncing murder of any kind. Zena posted it on our Facebook page, where it was quickly picked up by a Jewish newspaper. A few days later I saw the image pop up on a friend’s timeline. She had seen it on the site of a reporter from Al Jazeera who had seen it from a retweeted source. Thousands and thousands of people from very different political perspectives shared that image. Zena’s picture had struck a chord of shared humanity.

Again, I don’t believe that these small tokens will stop the violence on the other side of the world. The only place I have (even a little) control is over my own heart and my own mind. But things are fundamentally interconnected. I see that beginning with my own body. When one part of my body is injured, other parts shift to compensate for it. Small things in one place create reactions in other places. And we can’t always predict how things will unfold.

We can indeed sit with anger, hatred and despair. And we can take political action in ways that make sense to us. But there is also something subversive about contributing to the discourse in a way that fosters the kind of openness that each side deplores the other side for lacking. Things do not have to be this way. I believe this with perfect faith.

If you agree, please add your voice. Let others know of your hope, your openness, your vision. Share examples of people you know who are living in Israel and Palestine and who inspire you in thinking things can be different, better. And God willing, may it soon be so.

Jul 15, 2014 | Email Newsletter Full Article

by Rabbi Arthur Green

Zalman, like Heschel and a few others (I am so incredibly blessed to have had them both as teachers!), understood that Judaism is all about the devotional life. יידישקייט איז א דרך אין עבודת השם, he would say in clearly understood Yiddish, “Judaism is a pathway for the service of God.” We are here to serve, and a teaching takes on real meaning only if it inspires you to that service in both its inward and outward forms.

So my line for talking about Zalman here is a line from tefillah (prayer), rather than a verse from Torah. It is a line we know well from the Ne’ilah service:

פתח לנו שער בעת נעילת שער כי פנה יום

As I talk about it, or say some things about Reb Zalman through it, I also ask you to daven (pray) it, hopefully taking my words as a kavvanah (intention), as he always wanted his words to be taken.

פתח לנו שער Zalman was a gate opener. He gave special care to people at the beginning of their Jewish journeys. He always taught and wrote accessibly, warmly welcoming people into the tradition. Of course he didn’t care who you were: Jewish, non-Jewish, committed Sufi, Christian monk or nun, Buddhist practitioner – you were all welcome. He recognized how difficult a path mystical Judaism could be for beginners and he tried to change that. In a completely transformed world, one following the paradigm shift of which he spoke so often, he was following the example of the head of his spiritual lineage, R. Shne’ur Zalman of Liadi, in writing the Tanya. What are the things you really need to know, RaSHaZ asked himself, and how can I say them in a devotionally stirring manner? That was R. Zalman as well.

The gate. That of teshuvah (repentance), of course. But also the gate to the great palace, the hekhala de-hekhlin (supernal palace) of religious experience, of being in the presence. Zalman wanted to open the gate for you in an experiential way, to give you – even at the beginning of your journey – a glimpse of the great light that he saw shining within. Zalman was, to those of us who knew him well and not only reverentially, something of a religious experience junkie. He wanted to take you along within him in that. Yes, of course he had read the Ba’al Shem Tov’s parable about the king who builds a grand palace of optical illusion – he knew the palace was an illusory one – and here comes a great belly laugh from Zalman, saying “Yes, OF COURSE I’ve seen through it all” – but in knowing that the palace is illusion, the light that shines through is even brighter… ”Only you and the King are there alone.”

The gate is also that of Kafka’s famous parable “Before the Law,” which Zalman knew well. “This gate was made for you alone,” says the gatekeeper as he swings it shut at the end of our lives. For Kafka, that was the gate we never entered, too shy, uncomfortable, insecure, ambivalent, to step through it. Zalman wanted to be sure he was right there at your gate – the unique way in that would work only for your שורש נשמה, the root of your soul. “Welcome,” he would say, “don’t just stand there saying, ‘פתחו לי שערי צדק, someone open the gate for me!’ זה השער לה’ צדיקים יבואו בו, learn to do like the tsaddikim (righteous), who just walk right through. Welcome to being, speaking, and feeling like an insider to the tradition.” Zalman taught us to speak unselfconsciously of Avrohom Ovinu (Our father Abraham) and the Riboino shel Oilem (Master of the World), instead of “Abraham” and “God.” He made us understand that the tradition was ours, ours to inherit, to love, and to make better – especially more inclusive – as we pass it on. The Hasidic phrase, הרחבת גבול הקדושה, broadening the boundaries of the holy – also much loved by Rav Kook – was key to Zalman, and he gave it to us with a sense of authenticity that allowed us to go in his path. That was a great gift, one that we need to use with great love and great responsibility.

בעת נעילת שער, open the gate for us – at a time when the gate is closing. Zalman felt the terrible loss caused to the Jewish spiritual tradition as well as to the Jewish people by the Holocaust. In the early years – I had the privilege of knowing and hearing him first in the late 1950’s – he would speak often of the lost masters and teachings that had gone up in smoke, the shittot (approaches) in vodat ha-shem (worshipping/serving God) that we would need to recover or re-create, because they’d been obliterated. Lineage was terribly important to him; it remained so when he saw it being called upon by various Indian and Eastern teachers who claimed unbroken chains of tradition. His heart ached for the closing of gateways that had been brought upon us by this terrible history and that of our long history of victimhood. He wanted to recover pathways from the past that had been lost along the way, even long prior to the Shoah. The Jewish/Sufi path of R. Avraham ben ha-RaMBaM, for example, or the meditations on oneness of R. Aharon of Starroselye, the great disciple of RaSHaZ. “Don’t let any of those gates close!” Zalman would say. “There are souls out here who can enter only through them!” Yes, that would also include musical gateways, so-called “secular” gateways through the path of Yiddish literature, which he appreciated and loved, and lots more.

But he also saw the נעילת שער ”locking of the gates” that an overly insular and sometimes xenophobic community of the pious had brought about. “Unless you are willing to be completely frum in the traditional sense, there is no entry for you.” Zalman fought against this his whole life. (I recall his “sliding scale” of kashrut observance, back in the ‘60’s, as an early example.) He tried in those hard years of transition to make for a broadened and open-minded HaBaD Hasidism. Eventually he saw that he had to make the break, doing so with wrenching pain that was never entirely healed – on either side. He saw the locking down of those gates as a tragedy for the tradition as well as for those souls – Jewish and non-Jewish – who would be left outside. We who stand within the tradition NEED them! “Why are they such seekers?” He would ask. “Why are the ranks of every guru’s followers in the world overloaded with Jews? Because of ibbur neshamah (reincarnation).” Those millions of souls slaughtered in the Shoah, especially the children who had not yet found their spiritual paths in life, wander about the world and impregnate the souls of Jews and others in the next generation with a longing for Torah. “How DARE we keep them out?” he would say.

כי פנה יום, for the day is passing away. Zalman was fully aware of the times in which we live and of the urgency of great teshuvah (atonement), not only for us Jews, but for the human community as a whole. This was where Zalman and his special disciple Arthur Waskow became brothers. Beyond the “paradigm shift” was “the great urgency of Now.” Learning to translate the Tanya’s שער היחוד והאמונה into the language of Gaya, with its sense that the divinity within the earth, that which is dressed in the garb of nature, so much needs us to change the way we live, to recognize the sacred within all things and to respect it, to turn toward a greater simplicity of living in the world in order that we all survive and thrive – this became an essential part of Zalman’s message. It is indeed very late. We stand before the closing of gates greater than any we can imagine. This vision of a renewed sacred path of living – a spiritually reinvigorated, but open and embracing Judaism, alongside the same version of every other great spiritual tradition in the world, is all we have to save us. It is indeed very late in this day of at-one-ment (Zalman’s quip, of course), a day that needs to be every day.