Sep 12, 2016 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

Scene one: I went to the local farmer’s market and bought some berries. I brought them home and when I opened the box to finish my lunch with fresh fruit, I noticed that the whole package was laced with mold. I was annoyed; the berries weren’t cheap! I grabbed my purse and the box and marched back up to the market in the hot afternoon sun. I got in line at the stand, only to be told by the woman in front of me that the line actually wound down the street and I had to go and stand over there. Just as it was my turn to move up, another woman, who also didn’t understand how the line worked, edged in to step before me. I curtly informed her that the end of the line was over there. She blinked, stood a moment, then put her items back and walked away, telling me that she hoped I didn’t hurt other people the way I had hurt her. Confused and contrite, I apologized, but she tossed a rude gesture over her shoulder and didn’t look back.

Scene one: I went to the local farmer’s market and bought some berries. I brought them home and when I opened the box to finish my lunch with fresh fruit, I noticed that the whole package was laced with mold. I was annoyed; the berries weren’t cheap! I grabbed my purse and the box and marched back up to the market in the hot afternoon sun. I got in line at the stand, only to be told by the woman in front of me that the line actually wound down the street and I had to go and stand over there. Just as it was my turn to move up, another woman, who also didn’t understand how the line worked, edged in to step before me. I curtly informed her that the end of the line was over there. She blinked, stood a moment, then put her items back and walked away, telling me that she hoped I didn’t hurt other people the way I had hurt her. Confused and contrite, I apologized, but she tossed a rude gesture over her shoulder and didn’t look back.

Yuck.

Scene two: It was a rainy morning, which somehow always means the subway is more crowded. I managed to squeeze my way in so I could get to work on time, only to end up on an express train that stopped between stations and sat for long minutes. A man in the car was demonstrating a new game on his phone to his friend. Apparently, he didn’t know you can turn off the sound and everyone was forced to listen to the endless insipid loop of music punctuated with little “whee’s!” and “ka-ching’s!” Did I mention it was loud? I breathed. I said to myself, “This is unpleasant.” I felt my annoyance rise in my chest. Then the man in front of me started dancing a goofy dance to the music and I had to laugh.

Ahh.

As we come into Elul, I am considering the interconnected nature of our actions. Sometimes I think that the way to actually know the underlying Oneness of everything is through certain kinds of mystical experience, but then I begin noticing how just paying attention to what we do brings the same insight home. My grumpiness is infectious. It rises up and pours out in my words, my tone, my body language. It makes another person’s bad day even worse. The same is true for joy, as well. The same is true for love. We are so profoundly interconnected as individuals. How much the more so are we interconnected as communities and nations and species on this small planet!

My intention for Elul is to become as awake as I can to the intended and unintended consequences of my actions. And who knows? Perhaps that will help prepare me for a more mystical experience of interconnectedness as the High Holy Day season begins next month.

Aug 5, 2016 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

It’s getting to the point where I dread checking the news or signing onto Facebook. The spiking of violence in so many parts of the world, including on our own streets, the unbridled vitriol, the screaming without listening, the hot rage – perhaps I am getting old and myopic, but I don’t remember seeing this much venom before. I feel my heart close up, pressure in my throat. It is so profoundly unpleasant. I dislike the anger rising up in me and I want to turn away. But somehow I can’t.

I am also aware that we are currently in the three weeks of mourning leading up to Tisha B’Av, which will be observed on August 14th this year. Some years, I must confess, this day commemorating the destruction of the Temples in Jerusalem feels a little counter-intuitive to me. It’s summer! It’s a time of abundance! And what is this about the Temple? Perhaps I can grasp it as a symbol, but really, why focus on grief and mourning now?

Then I read an excerpt from Rabbi David Jaffe’s soon-to-be-published book, Changing the World from the Inside Out: A Jewish Path for Personal and Social Change. Rabbi Jaffe differentiates between “hot anger,” which is passionate and explosive, and “cold anger,” which is grounded in grief and loss. According to Jaffe, this cold anger can lead to creative solutions to intractable problems. And I thought, “Aha!”

The rituals of mourning that accompany Tisha B’Av can help me surface the grief and loss that is lurking under the despair and anger. There is so much to grieve: the lost lives, the disintegration of civil discourse, the loss inherent in not feeling safe, the fear that all of this evokes. When I sit with the grief that is under the other emotions, I can connect back to my heart. I can feel my own vulnerability and humanity. I might even feel the vulnerability and humanity of those I cannot stand because I sense their grief as well. After all, we are so profoundly interconnected.

Tisha B’Av moves us from mourning into Shabbat Nahamu, the first of a cycle of readings of comfort and consolation. As my meditation practice these days, I am focusing on a chant to the words “Ahavah verahamim, hesed veshalom” – love and mercy, kindness and peace. It helps me both allow the grief to surface and to cultivate the qualities I sense are missing in the world. It is a comfort for me and one which I hope brings strength and loving commitment to a better world.

Jun 21, 2016 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

Last week I had the opportunity to be in Los Angeles for Father’s Day. I was delighted to celebrate with my family by going up to a picnic area by a small creek – complete with a waterfall – in the San Gabriel Mountains. When I was a child, we would often escape the heat and smog of Southern California by going to this lovely canyon with its white granite walls, the cold honey-colored water, the smell of oaks and sage. It was the definition of summer time.

Summer brings us out into the world in ways that we often don’t have during the rest of the year. Sometimes it is a pleasant experience – warmth, greenery, the long days. And sometimes it is less pleasant, too hot or too humid.

But in any case, it gives us the opportunity to experiment with a teaching from one of the texts we often teach in our cohorts. It comes from a very early Hassidic source, Likkutim Yekarim: “A high rung: Always consider in your heart that you are close to the blessed Creator, that God surrounds you from every side. … Be so attached that the main thing you see is the blessed Creator, rather than looking first at the world and only secondarily at God. God should be the main thing you see.”

A high rung indeed! And a beautiful thought experiment as we move outdoors this summer. What would it be like to experience the world through the lens of “This is God”? God: the creek. God: the oak and sage. God: the rattlesnake. God: the humidity. God: the crush of people in the city. God: the open expansiveness of vacation.

If you wish, I’d love to hear how the experiment goes. And in the meantime, I wish you a summer of delight!

Jun 3, 2016 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

It seems to me that Shavuot, the holiday that celebrates the revelation of Torah at Mt Sinai, is an extraordinary opportunity for us to explore listening as part of building our capacity to hear God’s voice. For some, that might not be such an intuitive suggestion. Even if we “believe in” God, which not everyone does, the idea of hearing God’s voice seems archaic. But it invites intriguing questions or thought experiments: How would we know what God’s voice sounds like? What would it say if we could hear it? How would we know that is the voice of Divinity? What practices might help us cultivate more attuned ears?

I have always admired, and committed myself to develop, the ability to listen more deeply, to bring my full empathetic presence to the person speaking. I know that when others do that for me, it helps me to hear my own truth with greater honesty and insight and to explore more deeply than I might have otherwise. When I am listened to in this way, I feel seen and held. In this noisy world filled with bombast and interruptions, that attentive listening can feel like a gift of cool water on a hot day.

Recently, I’ve noticed the emergence of another experience of listening. This listening seems to emanate from a very calm, still point at the solar plexus that moves out and creates a kind of contained spaciousness. When I listen from this place, I notice my emotions are less engaged, not because I have become cold and callous but rather because I am more able to get out of the way for the sake of the person I am listening to. This kind of listening feels very clean and holy to me; it is one I want to continue to cultivate.

One additional suggestion for exploring how to listen in a new way is one I learned from Norman Fischer. He gave a meditation instruction that began with listening to the ambient sounds, whatever they may be: birdsong, traffic, voices, music. Then, he taught, shift your attention and start listening instead for the silence (or perhaps Silence) from which all sound arises and to which it returns. What might you hear?

Maybe this Shavuot we can practice listening more deeply, respectfully, lovingly to the people around us. Maybe we can practice listening to the sounds of the world. And maybe we might hear a Divine voice. May whatever we hear bring blessing.

May 2, 2016 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

In my experience, Passover is a holiday that often fails to reach its potential to help us wake up to the power of transformation. The form of the holiday is so overwhelming: the occasionally obsessive attention to food and cleaning; trying to find the right balance of keeping everyone engaged and interested at the seder; the joys and pressures of hosting and being hosted.

And yet, Passover offers an opportunity to explore transformation like no other holiday, not even the High Holidays. The High Holy Days invite us inward, towards repentance. Passover explicitly links our inner liberation with liberation in the greater world and does so in the context of love.

How so?

Passover first invites us into our actual experiences through the eating of the ritual foods, the karpas, matzah and maror. For many of us, these foods are the only foods we eat mindfully all year! The attention to sensation in the mouth (and sinuses, in the case of horseradish) brings us into this moment with full presence. It invites us to investigate what is happening in the body now.

In addition to noticing the truth of our experience, the haggadah reminds us that in every generation we have the opportunity to see ourselves as if we personally left Egypt. This can prompt us to pause and ask ourselves what transformation we are seeking in our personal lives. There may be times at the seder itself that we experience constriction. Perhaps it is around a strained relationship with someone at the table or connected to a religious or political struggle. What would it look like to experience greater liberation in regards to that constriction?

Furthermore, the seder is filled with explicit and hidden references to redemption in the greater world, thereby linking personal liberation and liberation more generally. For example, the story of the five rabbis discussing the exodus from Egypt all night until their students came to remind them to recite the morning prayers is actually a coded story. According to some sources, the rabbis were so inspired by their reenacting of the Passover story that they planned a revolt against the oppressive Roman Empire, instructing their students to warn them with a cryptic phrase about the Shema if a Roman soldier happened to pass by. Our individual liberation is deeply linked to working for liberation in the world, towards welcoming in the spirit of Elijah and an era of greater justice and peace.

And perhaps most important of all, this whole story is framed in the springtime and the Song of Songs, the Bible’s sweet love poetry. The imagery of blossoming and fragrance, beauty and intoxication, the playful hide and seek (and find!) of lovers in a spring time garden reminds us that even when the work of liberation is exhausting and discouraging, love is still available. In fact, love is the foundation that allows the transformation to take place.

So in the midst of the cooking, cleaning, engaging, hosting and being hosted, may we all find a few moments to touch down into love, into mindfulness, and into the connection between personal and communal liberation so that we all may experience greater freedom and possibly even redemption.

Dec 30, 2015 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

Is it just me or does the world seem particularly dark these days?

I remember periods when everything seemed flush with potential and vibrant with possibility, but these times seem heavy with a kind of dread. We continually see cruelty and bloodshed splashed across screens of all sizes; in so many of our personal circles we have experienced loss and displacement as well. And this is not to mention the fact that the cherry trees were blooming in New York City on Christmas Eve–a wondrous and terrifying disruption.

How am I supposed to respond?

The unique contribution of the Institute for Jewish Spirituality is that we are working to infuse the lived life of Jews with meaning and wisdom through spiritual practices that open the heart and nourish the soul. These capacities are crucial to helping us respond to the darkness.

When my heart sinks in despair at the entrenched systems of suffering, my meditation practice reminds me that things do change and sometimes in surprising ways. When I feel rage rise in me at all those idiots out there, my weekly learning with my study partner helps me notice anew all the nekudot tovot, the points of goodness, in others and in my own life. When I want to turn away in self-protection, my prayer practice urges me to keep my heart open and to listen more carefully.

And my practice also reminds me to notice the blessings of love and health and fulfillment in my own days and to give thanks for them. As the poet Jane Kenyon wrote, “It might have been otherwise.”

Over and over again I find that these practices are a lifeline for me in living a Jewishly meaningful, responsible, compassionate life, even when the world feels dark.

Dec 7, 2015 | Uncategorized

From Chamber to Chamber

Rabbi Jordan Bendat-Appell

דע שיש חדרי תורה, ומי שזוכה להם כשמתחיל לחדש בתורה, הוא נכנס בחדרים, ונכנס מחדר לחדר ומחדר לחדר, כי בכל חדר וחדר יש כמה וכמה פתחים לחדרים אחרים…אבל הכלל שאסור לטעות בעצמו, לסבור שכבר בא אל ההשגה הראוי, כי אם יסבור כן ישאר שם חס ושלום

“Know that there are chambers of Torah, and one merits them when one begins to renew Torah; one enters into the chambers, and goes from chamber to chamber and chamber to chamber, for in each and every chamber there are several openings to other chambers… The most important thing is not to fool yourself, thinking that you have already arrived at an adequate understanding. For one who thinks this will remain there, God forbid.”

— Rebbe Nachman of Bratslav, Likutei Moharan, 245

It is so easy to walk around the world and relate to it as if it was a known, fixed entity. The phone rings and we assume we know exactly what the caller wants and how it will make us feel. Our coworker or partner approaches us and we may default to an assumption that we know what it is he wants to say (for the millionth time!). We get in our car and we assume that the experience of our commute must make us feel bored and despondent.

In this passage, Rebbe Nachman urges us to relate to Torah as a new chamber, unknown and fresh—not as the same texts we read last year. This lesson can be applied to everything in life—we can relate to each moment as a new chamber of life, ever unfolding in surprising ways. This orientation of renewal—the bedrock of hitlamdut—is about having an ongoing sense that “I don’t know.” Hitlamdut creates an opening for renewal, a possibility of experiencing continuous growth in our relationships and experiences.

Nov 23, 2015 | Uncategorized

“Meditation? Me?

Why would I want to spend time sitting and focusing on my breath? I’m not the type…”

When I remember that version of myself, five years ago—someone who was not the “type” to meditate—I smile and am filled with gratitude. Gratitude toward my former self, for staying curious, which enabled me to follow a deeper yearning for connection. And, gratitude to the Institute for providing a safe space for inner work, and teachers who inspired me to explore Jewish contemplative practices.

The change in my life is palpable: more joy, less worry, more appreciation for all the blessings around me—blessings which I now am able to notice in their fullness and beauty. One very vivid example is my experience of aging. Yes, I worry about growing older and losing my physical vitality or mental acuity. But while I have never felt more vulnerable, I have learned to embrace it; I ask God for strength and in the stillness and spaciousness of my breath, I am at ease.

— Terry Rosenberg, West Newton, MA (Incoming Board Chair, Kivvun)

how do you remain open to learning?

who are your teachers?

Have you learned anything unexpected from an every day experience?

a challenging experience?

A text study on Hitlamdut by Rabbi Jordan Bendat-Appell,

featuring the teachings of Rebbe Nachman of Bratslav.

“In this passage, Rebbe Nachman urges us to relate to Torah as a new chamber, unknown and fresh—not as the same texts we read last year. This lesson can be applied to everything in life…”

Click here for the full text study.

Learning about and practicing anavah (humility) could not have come at a better time; it saved me by helping me to reevaluate my life and escape the pressures of needing to prove myself. I was so used to defining my value solely by my successes, as opposed to by my passions or relationships. Tikkun middot practice helped me realize that what I accomplish—and don’t accomplish—does not define my worth.

— Madeline Dolgin, NYU student (Tikkun Middot Project)

What awakens

your curiosity?

Tell us in the comments below!

Sep 21, 2015 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

It seems to me that this year more people are going public with their discomfort with Avinu Malkeinu, the prayer of supplication that is one of the hallmarks of the High Holy Day liturgy. I suspect that much of the discomfort is due to the difficult metaphors that form the refrain of the prayer, addressing God as our Father and our King. Many of us avoid using male language in reference to God so we try to “fix” the prayer by gender-neutralizing it to “our Parent, our Sovereign” (which feels vague and unsatisfying to me). The real problem is actually deeper: We are stuck with these images of God that either infantilize us or just are so out of our lived experience that they leave us cold. And the explanation that “Avinu” is supposed to be about forgiveness and “Malkeinu” is supposed to be about judgment doesn’t help very much.

But—perhaps appropriately for Yom Kippur—I have a confession. The truth is that I absolutely love Avinu Malkeinu. I always feel disappointed when the holidays fall on Shabbat and we don’t get to recite it. My eyes often fill with tears just opening the machzor, the High Holy Day prayerbook, to that page.

Here is why: A teacher of mine once explained the metaphor like this: “Avinu” (our Father) is about much more than forgiveness. It is shorthand for the perfect parent, the one we all wish we had or could be. Avinu absolutely believes in us, loves us unconditionally, knows what we need and can always provide loving guidance. Avinu is endlessly patient, encouraging, and overflowing with compassion for our attempts to live the best we can in an often confusing and difficult world.

“Malkeinu” (our King), on the other hand, can be less about judgment and more about total surrender of control to a power against which there is no recourse. In the old days, the king could demand pretty much anything: your crops for his store houses, your sons for his army, your own body for his service. If you didn’t like it, that was too bad. There was no appeal. While most kings don’t have that power any more, the truth is there are plenty of important things we still cannot control. Malkeinu is everything that profoundly affects our lives over which we have no power, all the circumstances that we must comply with, whether or not we like it.

And then this extraordinary combination of boundless compassion and absolute power becomes the recipient of our deepest yearnings: Please, let this be a good year. Let our needs be taken care of. Let there be less suffering. Let these things happen in realms over which we have no control. And let them happen even if (even though) we have done so little to deserve them.

Sometimes it takes that evocation of a listener to remember and then utter our most vulnerable longings. And sometimes the fervent expression of those longings is its own answer.

May we all be sealed for blessings of compassion and abundance, joy and connection, in this New Year.

Jul 8, 2015 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality, Email Newsletter Full Article

One of the great challenges of spiritual practice is not to confuse the form with the purpose. For example, when first learning to meditate, it is easy to assume that the practice is about noticing breath (or whatever the object of focus is) and that to be “successful” in meditation, you have to be able to sustain long, undistracted attention to the breath. But as we deepen the practice, it becomes clear that it is not actually about the breath at all. It is about many things: learning to live life with intentionality, noticing conditioning of all kinds, listening to the wisdom of the body, refining compassion and humility, cultivating dedication and concentration, just as a start. But it’s not really about the breath.

And yet, it actually is crucial to start with the breath. The breath is the form, the container through which these other benefits emerge. By using the structure of bringing attention to the breath, we can see more clearly what actually arises and experiment wisely with that. Occasionally we may be able to do this kind of work spontaneously without the form; sometimes the muse does strike us. But as spiritual practitioners (and good writers) know, more often than not, spontaneous wisdom and insight is a rare gift.

The same is true in prayer. Too often in the Jewish world we focus on mastering the form: the Hebrew, when to bow, sit or stand, all those words. In the world of Jewish prayer, it gets even more complicated, because, in fact, there isn’t just one form. We can work with the matbe’a (words of the prayer book), blessings, chanting, or hitbodedut (talking out loud to God)—each its own form to master. But in all cases, as we deepen our prayer practice, it becomes clear that it is actually not about the form. Just like in meditation, the form is the structure through which different kinds of experiences and experimentation can happen. Perhaps it is about opening the heart to God. Perhaps it is about opening the heart at all. Perhaps it is about cultivating gratitude and wonder or going deep into the unknown.

One way to differentiate between the form and purpose of spiritual practice is to practice with intention: Why am I doing this practice? What am I hoping or aiming for? Asking these question helps keep the form fresh. It infuses the form with possibility, with creativity, with aliveness. It is one of the things that can help make practice not rote, but transformational.

Jun 2, 2015 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

As a child, I was always the kid who loved hanging out with the older kids. I was the oldest child in my family but usually among the youngest in my grade and I liked the company of kids who were capable of so much more. In rabbinical school, I was the one right out of college who preferred my second career classmates. They had so much more life experience and were so much more interesting than my own age peers!

So it may come as no surprise that, although I was born just after the “Boomer” generation, I have been very interested in their experience of approaching old(er) age. And I am delighted that the Institute is adding an important voice to this conversation: a brand new book by Rabbi Rachel Cowan and Dr. Linda Thal, called Wise Aging: Living with Joy Resilience and Spirit.

This book is truly a delight. Edited by Rabbi Beth Lieberman and published by Behrman House, it is a warm, wise and often humorous exploration of the gifts and challenges of growing older. The challenges might be more obvious than the gifts: the changing body, living with loss, confronting mortality. And yet, the gifts that can emerge are marvelous. Consider the possibility of renewing and repairing essential relationships or of developing the capacity to be more joyful, patient and generous. Consider the possibility of really thinking through what kind of legacy we wish to leave and the opportunity to finally bring our lives into greater alignment with how we have always wanted to live.

Aging, if we approach it wisely, gives us the opportunity to integrate all the learning we have done, especially the spiritual learning, regardless of whether we began early or late, so that we can live with greater meaning, less fear, more love.

Rachel and Linda designed the book to be used in Wise Aging Groups, small facilitated groups where these questions can be explored in safe, sacred community. Through our Wise Aging Training Program, we have trained more than 180 facilitators across the country, most of whom are offering Wise Aging groups on a local basis. But even if you don’t live in a community where a group has been formed, pick up the book. It draws you in and helps open the heart.

Mar 2, 2015 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

It is true that I recently got engaged, but it is also true that I had been contemplating love for some time before I met my beloved. In fact, one of the great benefits of having been single for such a long time was the experience of many kinds of love from all kinds of expected and unexpected sources: from family and friends, students and teachers. And also from sunshine and boulders and from characters in books. From relatives long dead. From God.

At a recent retreat, we had the privilege of learning with Dr. Melila Hellner-Eshed, who introduced us to the Idra Rabba, highly esoteric passages from the Zohar. According to these mystical teachings, the most ancient, primordial manifestation of God continuously trickles forth love as light or milk, without any will or effort. There are other manifestations of God that are more concerned with justice and morality, but the most fundamental nature of existence is this image of love. (Of course, the Zohar circles back to say that even though it may seem that there is a “most” fundamental aspect, everything is really a unified whole – but that’s another topic.)

Somehow it makes sense to me that if you strip everything else away, what is left is love. It is often what I experience when I reach a deep place in my practice, whether it be in meditation or in prayer. Sometimes I can sense that loving connection that is independent of will or effort. It simply is.

And this calls to mind another distinction which has been part of my musings about love: the difference between yearning and desire. Yearning is a spiritual stance, an orientation of longing to connect with that fundamental love. It is not about obtaining anything or getting any answer. In fact, yearning is its own answer.

Desire, on the other hand, is focused on an object, human or otherwise, which we may or may not acquire. It is easy to confuse with yearning, but in desire, we seek to be satisfied. And alas, as the Buddhists and others point out, desire is usually satisfied only temporarily, if at all. We often get bored with what we possess – and we experience great suffering when we do not get what we desire.

Desire arises and we can be skillful or unskillful in how we respond to it, but yearning can be cultivated as a devotional practice to help remind us of all the expected and unexpected places we might experience love. Not the love that demands conditions and reactions, but just the sweet generous love that flows in everything and which we can offer back as a gift in service of the Divine.

Mar 2, 2015 | Email Newsletter Full Article

By Rabbi Marc Margolius

The Institute’s Tikkun Middot Project integrates mindfulness practice with attention to a series of middot (spiritual/ethical qualities). This month, we are focusing on another essential Jewish spiritual trait as our middah of the month. Below you will find wonderful resources for meditation, embodied practice, and text study of the middah of kvetchitude.

Meditation of the Month: “Eh. Things could be better.” (The Veyizmir Rebbe)

Guided meditation: Close your eyes. Visualize any number of ways in which life could be better.

Embodied Practice of the Month:

Scrunch up your face tightly. Shrug your shoulders. Release. Sigh deeply. Moan. Whine. Repeat.

Text study:

And Adam kvetchethed to Eve: “For sure, we can eat anything. The weather is great. And the fruit is always in season. But would it spoileth some divine plan if we ate an apple, for God’s sake?”

(Bereishit Rabbah, midrash on Genesis 1.)

The people took to kvetching bitterly, saying “Oy” and “Vey iz mir.”

“Behold,” said Moshe to the Holy One, “they truly annoyeth me.”

(The Book of Numbers, ad nauseum. Also, see pretty much the whole Torah.)

“Hath we arrived there yet?”

“You calleth this a meal?”

“What? No Evian? Alright, alright. I guess tap water will do.”

“So, whence cometh the brisket?”

“One would thinketh the towels could be thicker, no?”

(Selections from Bamidbar Rabbah, midrash on Book of Numbers.)

Ben Zoma said: Who is wise? One who learns from everyone.

Who is mighty? One who subdues one’s passions.

Who is rich? One who rejoices in one’s portion.

Who is honored? One who honors one’s fellow human beings.

Who is miserable? One who wins the lottery and kvetches that last week’s pot was bigger.

Others say, one who complains loudest that the bagels were gone by the time he (some say she) reaches the buffet. (Others versions: the lox, not the bagels.)

Some say, who is miserable?

One who just moved one’s car and forgot that alternate side parking hath been suspended (this view is observed only in New York City and walled cities).

(Mishnah Avot – Ethics of the Patriarchy 1:4, version discovered stuck in a menu at the 2nd Avenue Deli.)

Note: this post is a joke, in the spirit of Purim!

For more information on the Institute’s Tikkun Middot Project, click here.

Oct 15, 2014 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality, Email Newsletter Full Article

For the third time in a row, I got to spend Yom Kippur and the first part of Sukkot in Israel. For Yom Kippur, I went to one of my favorite synagogues in Jerusalem where the liturgy is traditional and the singing is joyful and powerful. For me Yom Kippur is such a day of supplication. It felt particularly fitting this year to spend it praying and singing and weeping in Jerusalem.

This year I noticed a feature of the liturgy that I hadn’t paid much attention to before. Towards the end of the Kol Nidre service, the traditional prayer book goes through a recitation of the Thirteen Attributes of God four times. These thirteen attributes remind us that God is merciful and gracious, patient, compassionate and forgiving. And then at the end of the day, in the middle of Neilah, after all the prayers and poems and recitation of sins, we return to the Thirteen Attributes, not four times, but a whopping seven times.

Now, it makes sense to me that we would begin the process of Yom Kippur with an emphasis on Divine compassion and mercy. This makes it safe for us to enter into this difficult day of truth telling, remorse and pleading. We trust that our words will be heard with love. But why do we conclude the day the same way?

It occurred to me that although we spend (or at least can spend) much of the day looking into the spiritual mirror, Yom Kippur itself is not always a day of actual inner change. In fact, I would say that it rarely is such a day. When darkness falls and we get up to resume our regular lives, we may have gained greater insight into our habits of heart and mind, but without ongoing practice, it is difficult to translate that insight into real sustainable change.

Perhaps that is why one tradition is that we are not truly, truly sealed into the Book of Life until Hoshanah Rabbah, the seventh day of Sukkot. We may conclude Yom Kippur feeling exhilarated, cleansed, redeemed, but there is more work to do. So we need those extra reminders of God’s merciful attributes. In fact, we need a full cycle of seven repetitions of them to encourage us to make the difficult on-going commitment to the spiritual practices that will help integrate our new intentions into our lived lives.

As we come to the conclusion of our yearly cycle and begin the new one, may we feel upheld by compassion, patience and grace so that we can take up the transformational work of a new year. Chag sameach!

Sep 23, 2014 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality, Email Newsletter Full Article

In some ways, it is a pity that Rosh Hashanah doesn’t fall on Shabbat this year. We are going to have to listen to the shofar.

Of course, listening to the shofar blasts is one of those visceral experiences that tell us, yes, the High Holy Days have arrived. It is like hearing Avinu Malkeinu with that familiar melody or tasting apples in honey: those quintessential Rosh Hashanah experiences in the body that simultaneously ground us in this moment and bind us to other Jews in other places and times.

Traditionally, observant Jews don’t sound the shofar (or recite Avinu Malkeinu) on Shabbat. This year, Rosh Hashanah falls on Thursday and Friday. But in some ways, this is the year for the shofar to fall still so that we can listen more deeply, with greater focus.

For many of us, this was a difficult summer. Menachem Nachum of Chernobyl, the Me’or Eynayim, noted that suffering often has the result of narrowing our awareness, so that we become more focused on our suffering. It can become quite a nasty cycle.

Listening, really listening, is one of the things that can help take us out of that cycle. Listening takes us out of ourselves and into connection with others. But sometimes it can be confusing. We may listen for what is new or unknown. Or we may “listen” for a particular agenda, to the stories that reinforce what we think we already know. Unfortunately, that often leads us back to the cycle of suffering.

The shofar will be sounded this year in all the places Jews gather; listening to it has the potential to take us out of ourselves and into connection with others. But often we think we know what we will hear. What if instead, we listened as if we had never heard the shofar before? What if we listened for the echo of the shofar in our own hearts? What if we followed a recent teaching by Norman Fischer and listened to the silence from which the blasts emerge and to which they return? How might that inspire us, comfort us, sustain us in this upcoming year?

May the practice of listening – to the shofar, to the suffering of others, to our own hearts – help us bring an abundance of blessings to our world in the New Year! Shanah tovah!

PS: Speaking of abundance, check out our Shmita blog! And if you are interested in learning more about the Me’or Eynayim, sign up for our text study!

Jul 15, 2014 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality, Email Newsletter Full Article

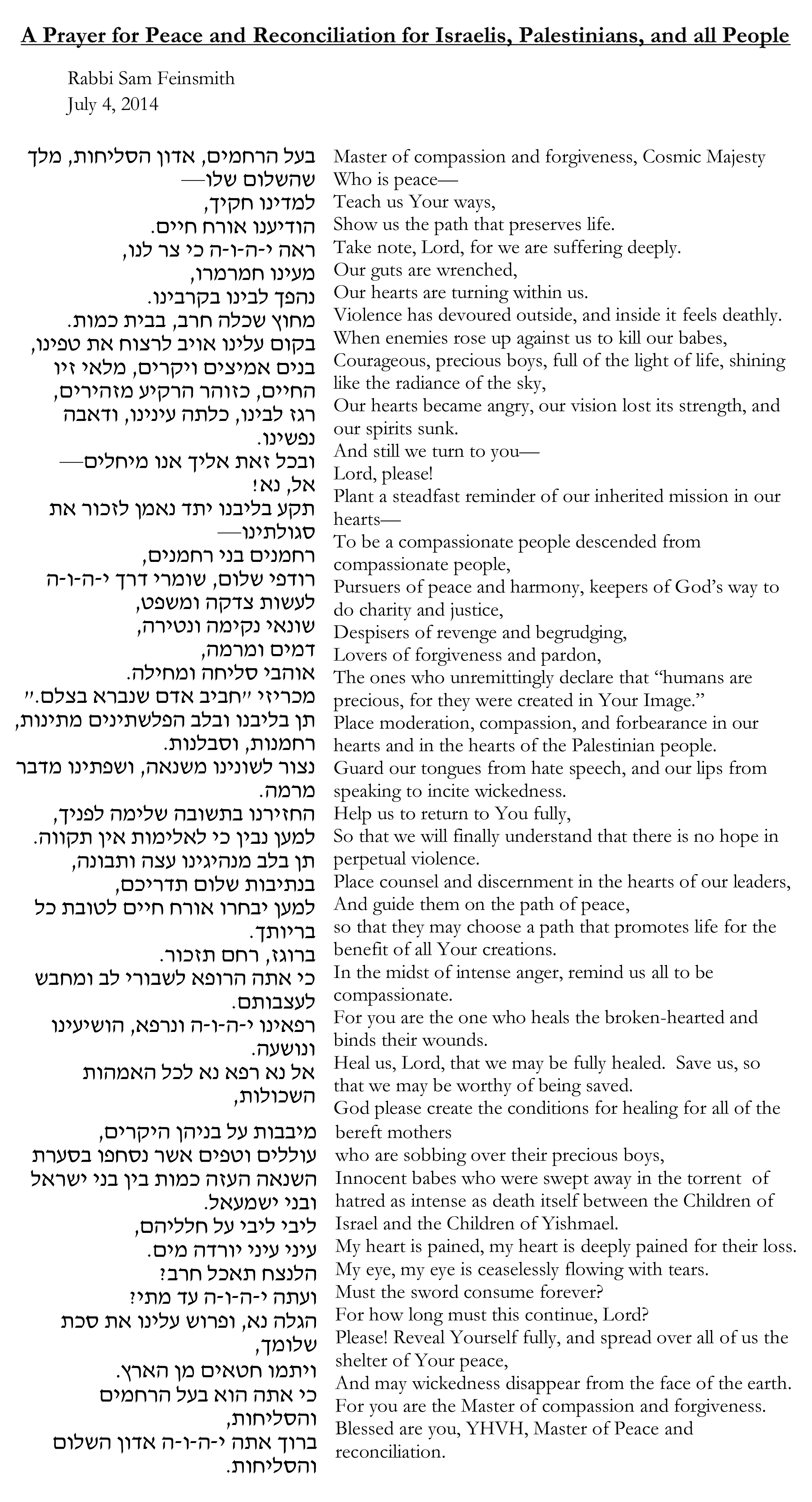

The other day I had coffee with a friend after work. We both were in a state of anguish about the violence in Israel and Palestine. She confessed that she was feeling despair; how could things ever get better? What could possibly be the catalyst for real change?

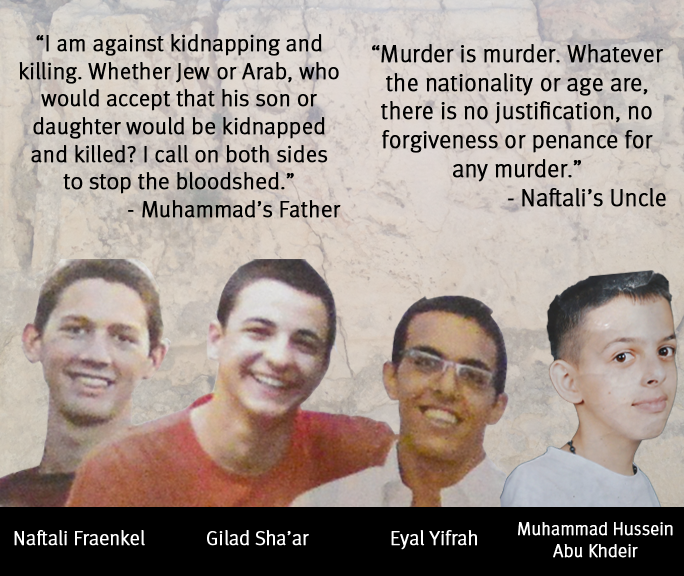

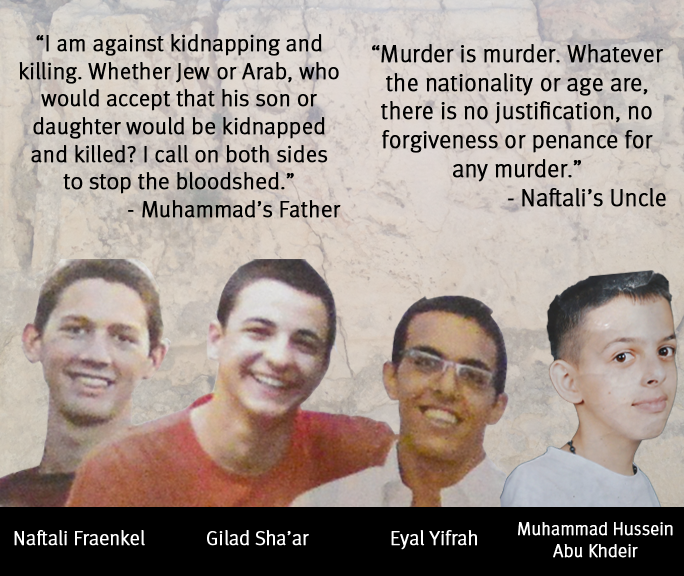

I thought about all the postings I see on social media. Ever since we learned of the murder of Naftali, Gilad and Eyal, and then the murder of Muhammed, and then the rockets and bombings, so much of the rhetoric has been justifying one side or the other or expressions of hopelessness. I feel the impact it has on my heart: I feel defended, closed, self-righteous. I experience how anger leads to more anger, despair to more despair. I feel my heart hardening into accepting the status quo cycles of violence and hatred as inevitable.

But it could be different.

How? I am so far away and so small. I am not naïve enough to think I can have any impact on Hamas or Netanyahu or anyone else who has power and weapons. And I am also not naïve enough to think that I am completely powerless.

If I want more hope, I have to add hope back into the system. If I want more openness to peace, I have to work on examples of openness to peace. If I want a vision of what could be possible in the turbulent land that I love with a full heart, then I have to speak out and encourage others to do the same.

A small example: Zena Schulman, our Communications and Development Associate, created an image last week of the four murdered boys along with quotes from their family members denouncing murder of any kind. Zena posted it on our Facebook page, where it was quickly picked up by a Jewish newspaper. A few days later I saw the image pop up on a friend’s timeline. She had seen it on the site of a reporter from Al Jazeera who had seen it from a retweeted source. Thousands and thousands of people from very different political perspectives shared that image. Zena’s picture had struck a chord of shared humanity.

Again, I don’t believe that these small tokens will stop the violence on the other side of the world. The only place I have (even a little) control is over my own heart and my own mind. But things are fundamentally interconnected. I see that beginning with my own body. When one part of my body is injured, other parts shift to compensate for it. Small things in one place create reactions in other places. And we can’t always predict how things will unfold.

We can indeed sit with anger, hatred and despair. And we can take political action in ways that make sense to us. But there is also something subversive about contributing to the discourse in a way that fosters the kind of openness that each side deplores the other side for lacking. Things do not have to be this way. I believe this with perfect faith.

If you agree, please add your voice. Let others know of your hope, your openness, your vision. Share examples of people you know who are living in Israel and Palestine and who inspire you in thinking things can be different, better. And God willing, may it soon be so.

Jul 15, 2014 | Email Newsletter Full Article

by Rabbi Arthur Green

Zalman, like Heschel and a few others (I am so incredibly blessed to have had them both as teachers!), understood that Judaism is all about the devotional life. יידישקייט איז א דרך אין עבודת השם, he would say in clearly understood Yiddish, “Judaism is a pathway for the service of God.” We are here to serve, and a teaching takes on real meaning only if it inspires you to that service in both its inward and outward forms.

So my line for talking about Zalman here is a line from tefillah (prayer), rather than a verse from Torah. It is a line we know well from the Ne’ilah service:

פתח לנו שער בעת נעילת שער כי פנה יום

As I talk about it, or say some things about Reb Zalman through it, I also ask you to daven (pray) it, hopefully taking my words as a kavvanah (intention), as he always wanted his words to be taken.

פתח לנו שער Zalman was a gate opener. He gave special care to people at the beginning of their Jewish journeys. He always taught and wrote accessibly, warmly welcoming people into the tradition. Of course he didn’t care who you were: Jewish, non-Jewish, committed Sufi, Christian monk or nun, Buddhist practitioner – you were all welcome. He recognized how difficult a path mystical Judaism could be for beginners and he tried to change that. In a completely transformed world, one following the paradigm shift of which he spoke so often, he was following the example of the head of his spiritual lineage, R. Shne’ur Zalman of Liadi, in writing the Tanya. What are the things you really need to know, RaSHaZ asked himself, and how can I say them in a devotionally stirring manner? That was R. Zalman as well.

The gate. That of teshuvah (repentance), of course. But also the gate to the great palace, the hekhala de-hekhlin (supernal palace) of religious experience, of being in the presence. Zalman wanted to open the gate for you in an experiential way, to give you – even at the beginning of your journey – a glimpse of the great light that he saw shining within. Zalman was, to those of us who knew him well and not only reverentially, something of a religious experience junkie. He wanted to take you along within him in that. Yes, of course he had read the Ba’al Shem Tov’s parable about the king who builds a grand palace of optical illusion – he knew the palace was an illusory one – and here comes a great belly laugh from Zalman, saying “Yes, OF COURSE I’ve seen through it all” – but in knowing that the palace is illusion, the light that shines through is even brighter… ”Only you and the King are there alone.”

The gate is also that of Kafka’s famous parable “Before the Law,” which Zalman knew well. “This gate was made for you alone,” says the gatekeeper as he swings it shut at the end of our lives. For Kafka, that was the gate we never entered, too shy, uncomfortable, insecure, ambivalent, to step through it. Zalman wanted to be sure he was right there at your gate – the unique way in that would work only for your שורש נשמה, the root of your soul. “Welcome,” he would say, “don’t just stand there saying, ‘פתחו לי שערי צדק, someone open the gate for me!’ זה השער לה’ צדיקים יבואו בו, learn to do like the tsaddikim (righteous), who just walk right through. Welcome to being, speaking, and feeling like an insider to the tradition.” Zalman taught us to speak unselfconsciously of Avrohom Ovinu (Our father Abraham) and the Riboino shel Oilem (Master of the World), instead of “Abraham” and “God.” He made us understand that the tradition was ours, ours to inherit, to love, and to make better – especially more inclusive – as we pass it on. The Hasidic phrase, הרחבת גבול הקדושה, broadening the boundaries of the holy – also much loved by Rav Kook – was key to Zalman, and he gave it to us with a sense of authenticity that allowed us to go in his path. That was a great gift, one that we need to use with great love and great responsibility.

בעת נעילת שער, open the gate for us – at a time when the gate is closing. Zalman felt the terrible loss caused to the Jewish spiritual tradition as well as to the Jewish people by the Holocaust. In the early years – I had the privilege of knowing and hearing him first in the late 1950’s – he would speak often of the lost masters and teachings that had gone up in smoke, the shittot (approaches) in vodat ha-shem (worshipping/serving God) that we would need to recover or re-create, because they’d been obliterated. Lineage was terribly important to him; it remained so when he saw it being called upon by various Indian and Eastern teachers who claimed unbroken chains of tradition. His heart ached for the closing of gateways that had been brought upon us by this terrible history and that of our long history of victimhood. He wanted to recover pathways from the past that had been lost along the way, even long prior to the Shoah. The Jewish/Sufi path of R. Avraham ben ha-RaMBaM, for example, or the meditations on oneness of R. Aharon of Starroselye, the great disciple of RaSHaZ. “Don’t let any of those gates close!” Zalman would say. “There are souls out here who can enter only through them!” Yes, that would also include musical gateways, so-called “secular” gateways through the path of Yiddish literature, which he appreciated and loved, and lots more.

But he also saw the נעילת שער ”locking of the gates” that an overly insular and sometimes xenophobic community of the pious had brought about. “Unless you are willing to be completely frum in the traditional sense, there is no entry for you.” Zalman fought against this his whole life. (I recall his “sliding scale” of kashrut observance, back in the ‘60’s, as an early example.) He tried in those hard years of transition to make for a broadened and open-minded HaBaD Hasidism. Eventually he saw that he had to make the break, doing so with wrenching pain that was never entirely healed – on either side. He saw the locking down of those gates as a tragedy for the tradition as well as for those souls – Jewish and non-Jewish – who would be left outside. We who stand within the tradition NEED them! “Why are they such seekers?” He would ask. “Why are the ranks of every guru’s followers in the world overloaded with Jews? Because of ibbur neshamah (reincarnation).” Those millions of souls slaughtered in the Shoah, especially the children who had not yet found their spiritual paths in life, wander about the world and impregnate the souls of Jews and others in the next generation with a longing for Torah. “How DARE we keep them out?” he would say.

כי פנה יום, for the day is passing away. Zalman was fully aware of the times in which we live and of the urgency of great teshuvah (atonement), not only for us Jews, but for the human community as a whole. This was where Zalman and his special disciple Arthur Waskow became brothers. Beyond the “paradigm shift” was “the great urgency of Now.” Learning to translate the Tanya’s שער היחוד והאמונה into the language of Gaya, with its sense that the divinity within the earth, that which is dressed in the garb of nature, so much needs us to change the way we live, to recognize the sacred within all things and to respect it, to turn toward a greater simplicity of living in the world in order that we all survive and thrive – this became an essential part of Zalman’s message. It is indeed very late. We stand before the closing of gates greater than any we can imagine. This vision of a renewed sacred path of living – a spiritually reinvigorated, but open and embracing Judaism, alongside the same version of every other great spiritual tradition in the world, is all we have to save us. It is indeed very late in this day of at-one-ment (Zalman’s quip, of course), a day that needs to be every day.

Jul 11, 2014 | Email Newsletter Full Article

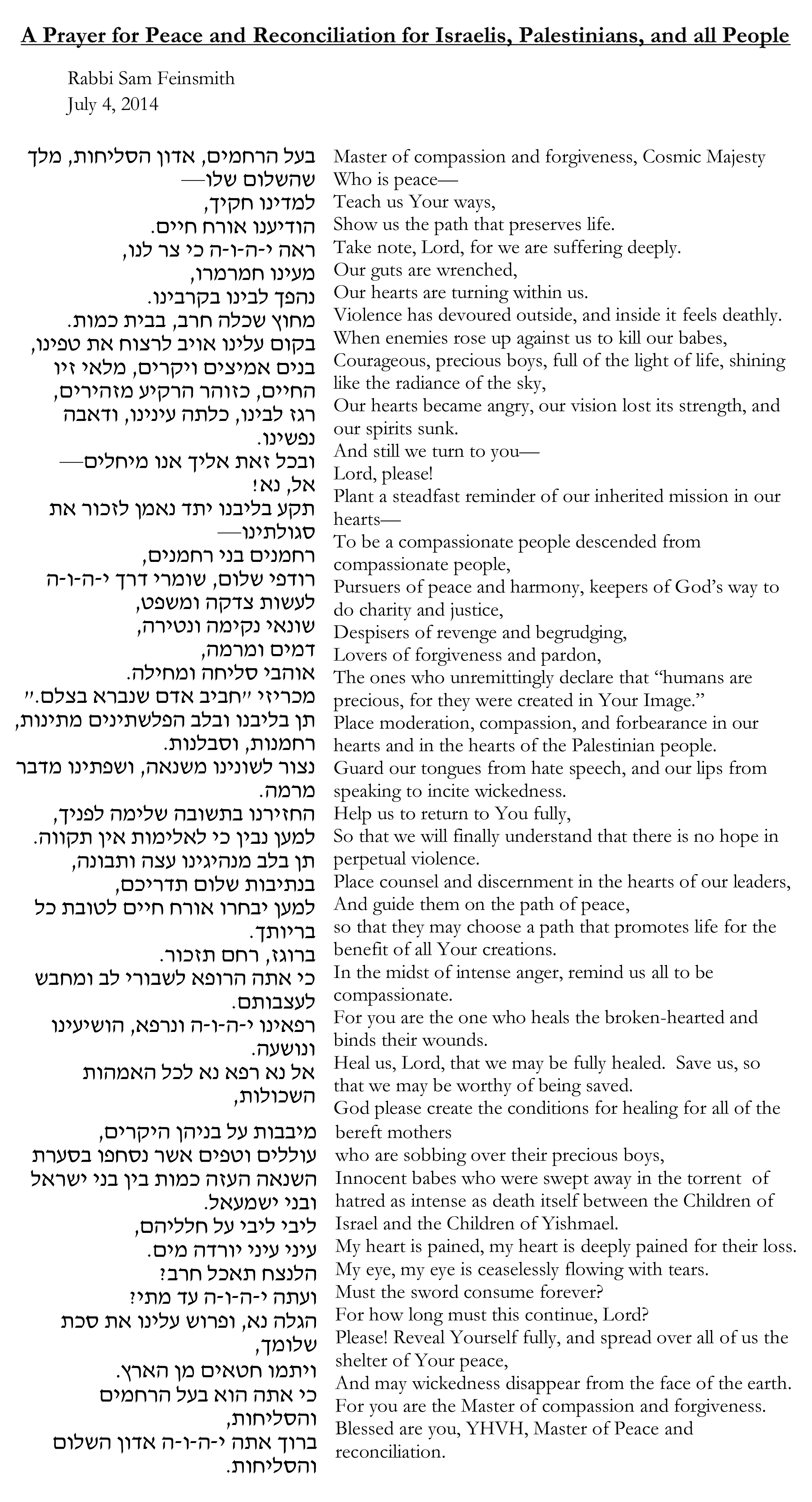

Jul 3, 2014 | Email Newsletter Full Article

By Rabbi Nancy Flam

“It’s hard to be a person.” That’s what my best friend from college says sometimes to console me when I’m having a tough time. I can’t hear those words without my heart softening. It is hard to be a person. And if the truth of that isn’t piercingly clear for you or me personally in this very moment, odds are it will be.

Today my friend Amy and I studied a couple of small pieces of Torah in the Hasidic collection, Itturei Torah (Volume 3, page 268) on the verse describing how God passed before Moses and declared God’s essential attributes (known as the Thirteen Attributes – Shelosh Esray Middot; Ex. 34: 6 – 7). About this verse Rabbi Yochanan is quoted in the Talmud as saying: “God said to Moses, ‘Every time that Israel sins, they will perform (literally: do) before me this seder (literally: order), and I will forgive them.’” The recitation of this seder – this liturgy- of the Thirteen Attributes assumed a central place in the yearly Jewish ritual enactment of forgiveness that takes place over the Days of Awe, beginning on the Saturday night before the New Year at the Selichot (“Forgiveness”) service. We Jews do indeed come before God with these very words, this seder tefillah, this liturgy of the Thirteen Attributes, and we plaintively recite them. We are comforted in knowing that, according to the rabbis, God cannot hear these words without compassion arising, without showing forgiveness. It’s as if God hears these words and softens, remembering with kindness: It’s hard to be a person.

The first small piece of Torah we studied by Alschich (1521 – 1593, Tzefat) pointed out that if one reads the Talmud text carefully one will notice that Rabbi Yochanan said that God instructed Israel to do (ya’asu) this seder before God, not say (yomru) it. Evidently, it’s not enough that we say these words to effect forgiveness. We have to enact these qualities that are attributed to God in our own lives (imitatio dei). We have to do them – to manifest them, to become them – and not just say them. That’s the work that is truly transformative. Perhaps Rabbi Yochanan’s teaching was directed to Jews in his own time who were relying too much on the ritual recitation of words alone, thinking that they would be sufficient to effect transformation, and weren’t working on themselves, cultivating day by day and challenging moment by challenging moment these essential qualities of compassion, kindness, patience and forbearance. They turned away from the hard work of being a person.

And then the second (unnamed) teacher in the anthology of comments on Rabbi Yochanan’s instruction regarding the Thirteen Attributes notes that we are told to do them “k’seder hazeh” which literally means “in this order”. Our teacher explains that this means “one should start with the first attribute: compassionate and gracious. [And as the rabbis have taught elsewhere,] just as God is compassionate and gracious, so should you be compassionate and gracious.” So, we are to “do” or make these attributes, not just say them. We are to become them in imitation of God. And furthermore, in this order: “Start with compassion. Don’t start at the end of the list: not remitting punishment, but visiting the iniquity of parents upon children and children’s children…”

I don’t know who gasped first. After a very long silence in which our minds each turned to the possibility of escalating violence, of acts of vengeance, of actions that could create harm for generations, one of us said something like, “Oh my God.” In this heartbreaking time in Israel and Palestine, Torah spoke with unmistakable clarity: Don’t start at the end of the list. Start with compassion. (The end might just then disappear.)

Jul 1, 2014 | Uncategorized

An interview with Rabbi Nancy Flam on the power of meaningful prayer is the featured story of the Fall 2014 issue of Reform Judaism magazine, and can be found at www.reformjudaism.org/revitalizing-prayer.

A new movement is emerging to transform prayer into a more powerful and compelling practice, building upon our ancestors’ recognition that we truly can effect change through prayer.

You have said, “We risk losing a core of Jewish religious life if we do not discover better ways to pray.” Why is discovering better ways to pray so important?

I believe that prayer is a fundamental, defining human need. When our hearts are full or empty, when we feel deep longing, gratitude, humility, awe, love, or devotion, many of us—even those who don’t relate to liturgical prayer in a formal service—instinctively turn toward prayer, just as a flower turns toward the sun.

One woman told me how she took a certain route each week when driving to an appointment in order to pass a beautiful field bathed in late afternoon sunlight—the sight always uplifted her. “I noticed the beauty and was grateful for it,” she told me. “Then I was grateful for eyes that could see, a heart that could understand, the happenstance of this incarnation….I’ve come to realize that my noticing is a prayer.”

Click here to read the interview in its entirety, and join in the conversation below!

Jun 2, 2014 | Email Newsletter Full Article

Rabbi Aryeh Ben David

Founder and Director of Ayeka: Center for Soulful Education

I felt like a shattered piece of glass. Intact, but splintered into thousands of pieces.

It was the moment of emerging from my first mikveh experience. Over 30 years ago, and still etched into my memory.

Broken and intact. Reconfiguring, changed. Putting myself back together into a new permutation. Renewed.

Immersion is easy to do in a mikveh. Full connection is the key to purification. I was naked vulnerability. I was open to allowing my life to fracture and be rearranged. I was full of dreams of a new and more pure version of myself.

How can we bring this model of immersion, purification, and renewal into a learning environment? How can we fully ‘dip’ into the waters of Torah? How can we bring nakedness and vulnerability into an ostensibly mind-centered activity?

I would like to propose a simple 4-step process that can offer us an immersion in our learning and teaching:

1. Listening

2. Talking

3. Talking

4. Listening

Step 1: I listen.

I listen for a line or section in the source that deeply resonates within me. I am open and exposed in front of the text. I allow the words to flow over me. What line was written just for me, for right now? I may have to read the text again and again. There are many who have a custom of dipping in the mikveh 7 times. Sometimes we need to immerse ourselves again and again until we are purified; sometimes we need to immerse in the texts again and again until they penetrate through our skin. I don’t proceed until something in the learning has touched my inner self.

Step 2: God talks.

I imagine God talking to me through the chosen text. What is God saying to me through these words? The text is an invitation to listen to God’s voice. It is not the water that purifies – water is the messenger from the heavens to connect me to something beyond. So too these holy words – they are messengers from heaven to connect me to God. What is God conveying to me, right now? What message do I need to hear?

Step 3: I talk.

God has opened the conversation. Now I respond. I open my mouth and talk openly about where I am and what I need to move closer to God, to live more in the Image of God. I don’t think it or reflect on it – I need to talk it aloud.

I see my fractured life and accept it. I verbalize what I am struggling with and how these verses address my situation. I articulate how these verses can heal and purify me. I bless and thank God for the opportunity to grow.

Step 4: God listens.

After talking, I sit with myself for a few moments. The early masters would sit for a few moments after praying, being with the moment. The ‘being’ allows for the broken pieces to reconfigure and reunite. It is a healing moment of being. I am emerging from the mikveh of my learning and am now becoming a new version of myself. Only God can rearrange the pieces. Only God can purify. The mikveh is a birthing process. I am pure because I am no longer stuck in my former self. I have transformed into a new self. This is the mikveh of learning – of being with my new self, of affirming that I can perpetually transform myself to become closer to God.

Open, naked, vulnerable, and seeking a personal connection with the Beyond. These are the prerequisites for full immersion – in a mikveh or in a learning setting.

Jun 2, 2014 | Email Newsletter Full Article

Rabbi Jonathan Slater

It is a delight and an honor to be able to bring these translations of some of R. Levi Yitzhak’s teachings out into the world, and to connect them to our own lived lives. I have tried to be concrete in suggesting how these teachings can be practiced daily, how they can be brought into our day-to-day experience. Here is an example for Shavuot:

We are taught in the Talmud (Pesachim 68b): R. Eliezer said: “On a Festival we have no other option than either to eat and drink or to sit and study”. R. Yehoshua said: “Divide it: half of it to eating and drinking, and half of it to study. In response R. Yohanan said: “Both come to their teaching from the same verses. One verse says, ‘[After eating unleavened bread six days, on the seventh day] you shall hold a solemn gathering (atzeret) for YHVH your God: [you shall do no work]’ (Deut. 16:8), while another verse says, ‘On the eighth day you shall hold a solemn gathering (atzeret); [you shall not work at your occupations]’ (Num. 29:35). R. Eliezer reasons that the atzeret is either entirely for God or entirely for you, while R. Yehoshua reasons that we divide it, half for God and half for yourselves.” … R. Eleazar said: “All agree in respect to Shavuot (called atzeret by the Sages) must be ‘for you’ too. What is the reason? It is the day on which the Torah was given.”

On Pesach we rejoice; we rejoice in our bodies that we have come out from slavery. This is a physical boon. On Shavuot the joy is because God gave us the Torah. But, receiving the Torah is only a spiritual joy, and it is difficult for the body to rejoice.

That is why the Sages taught that Atzeret must be also “for yourselves,” so that the body, too, will rejoice. In this way we will truly believe that Torah offers us two lives (chayyei olam): the life of the world to come and the life of this world. Scripture proves this: regarding the former it says, “In her right hand is length of days, [in her left, riches and honor]” (Prov. 3:16); regarding the latter, “It will be a cure for your body, [a tonic for your bones]” (ibid. 8). Therefore, the body will rejoice as well, exulting from bringing this awareness to heart.

Other Festivals are endowed with specific rituals to mark their observance. But, this is not the case with Shavuot. Therefore, the sages emphasize that it, too, is meant as a day in which we take delight, and is not only one of spiritual devotion. This is an invitation to Levi Yitzhak to emphasize the Hasidic attention to the body as a potential source of spiritual awareness. We come to perceive the presence of the divine not by withdrawing from the world, but by bringing even more focused and precise attention to it. It is there that we will come to know that all of creation is filled with God’s glory.

Levi Yitzhak is aware of this as well. He notes that when we experience delight in the body, it helps us to connect to our spiritual selves. Those activities that we find liberating – those that we choose, those that enliven the body, those that delight the body – free the heart and mind and soul to reach out to God in celebration and thanks. Those activities that we experience as limiting or burdensome, dull the spirit and bring darkness.

Perhaps, then, we might want to ask what is missing in our engagement in synagogue services. How might they be like “Shavuot” in this lesson: activities that are cerebral, where the meaning is an idea and experience ephemeral? If this analogy is to be helpful, then something like “food and drink” to engage and delight the body may be needed to enliven the experience, and turn it into a delight.

Here are a few suggestions for investigation:

- How might singing be utilized as a way to wake up the body? How does singing bring delight into the body in a manner that supports us in connecting to that which is not concrete?

- Much of the physical activity during services is simply standing and sitting (and a lot of the latter). How might other sorts of physical activity (shukling, swaying; dancing; movement of arms and legs) help to connect the awareness of the body, and its delight in movement, to the cerebral?

- What might clergy and congregants do to offer each other relief and support in their shared roles in congregational worship? Each have different responsibilities, surely, but might better understanding of those responsibilities, interest in the experience of the other and involvement in seeking the wellbeing of the other during services release energy in the body to make the experience a delight?

- Food is often the “reward” for participation in services. How might that relationship between physical delight and spiritual awareness be shifted?

Fatigue and boredom are the products of dissociation and alienation. Connecting again to our own inner experience – both of the spirit and of the body – can help to bring delight into our communal religious lives.

May 12, 2014 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality, Email Newsletter Full Article

When I was a little girl, my mother taught my brothers and me to make chains of colored construction paper, one loop for each day before a longed-for event. Each evening before going to bed, we would ceremonially tear one loop off the chain and know how many days were left. In the spring we counted down to summer vacation; in the fall I counted down to my birthday.

As a people, we are similarly counting down at this time of year. During sefirat ha’omer (the counting of the Omer), each evening for the 49 days following Passover, we ceremonially mark off one more day as we proceed towards the longed-for holiday of Shavuot, the celebration of receiving Torah at Mt Sinai.

When I was a child, the purpose of the counting was to hurry along time as much as possible. It was an answer to the impatient question, “How many days NOW?” But spiritual practice helps us see this process in a very different light. Rabbi Nachman of Breslov taught that we must continually strive to see hasechel sheyesh bechol davar, the intelligence, or even signs of Divinity, that can be found in every single thing. His devoted disciple, Natan Sternharz, also known as Reb Noson, connected this teaching to counting the Omer.

Reb Noson noted that signs of Divinity can be found not just in every item, but in time as well—every day, hour and minute in its own unique way. To an ordinary person dealing with transactions and traffic and responsibilities, it’s a tall order to achieve the constancy of awareness that would permit us to see those unique signs of Divinity every day, let alone every minute! So we have this time of counting to help us practice being more finely attuned to the unique holiness of each particular day. For those of you interested in Mussar, it is very similar to the Mussar world’s offering of kabbalot, small tasks or opportunities to practice a particular middah or characteristic. The counting of the Omer is a bounded, but intensive training period for awareness.

So the counting is not to hurry along time. The counting is there to slow us down, to notice. Today is the 28th day of the Omer. What is unique about it? Where will the holiness be? Where might I find signs of Divinity if I only knew?

Wishing everyone a counting filled with wonder and blessings and joy!

May 12, 2014 | Email Newsletter Full Article

By Rabbi Joshua Levine Grater

My kids are getting older, and with their aging, they are starting to ask questions about time, length of life and death. They understand the concept of being born, as they have cousins who have been born recently, and they understand that life ends, both from their obsession with Harry Potter, which has main characters dying, and from the fact that their dad is often out at night at a shiva minyan. We have had some amazing discussions over this Pesach time, as they now like to sit and “talk like grown-ups,” as they put it—about time, life, memory, and understanding the differences between 100 years ago, like when their great-grandfather was born, 1000 years ago, and 3000 years ago, like when Moses lived. They are still only 9 years old, so of course I reassure them that they have a long and beautiful life ahead of them. And I try not to burden them with my own neuroses about time, my own struggles with understanding and living within the construct that yesterday will never happen again, that each day forward is a day closer to an end that is always fast approaching, but—please God—is hopefully far off in the future.

It is so wonderful to be a child, innocent and free of these mental burdens that can both invigorate and infuriate adults, as we all deal in our own ways with the concept of time and the counting of our days. I remember lying in bed, as my kids say they now do, wondering what it is like to die, how it will be that the world will go on and on, for billions of years, without me? This can either paralyze us into a life of fear, or it can inspire us to a life of meaning. Most of us live somewhere in between. As Dr. Sherwin Nuland writes so beautifully in his landmark book, How We Die, “Against the relentless forces and cycles of nature there can be no lasting victory.” But, with faith, hope, values and meaning, we can achieve a life that will live on beyond us.

We mark occasions of time, both celebratory and painful ones, which serve as guideposts in the sea of a lifetime. 128th birthday of Pasadena, 69th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, bar/bat mitzvah, 13 year anniversary of 9/11 approaching, 66 years of the State of Israel—all important milestones in the life of individuals and nations. Yet, how many of us ever pay attention to the passing of each day, I mean really count and mark each day of our lives as important, meaningful, reason for celebration? As we are in the period known as sefirat ha’omer, the counting of the Omer, which counts the days from Pesach to Shavuot, I am thinking about counting our days, and focusing on the meaning of a day in our lives, which is the most concrete block of time that we all share in common.

Biblically, the counting involved the time from the second day of Pesach until Shavuot, 49 days, culminating in the barley harvest and the offerings of the first grains at the Temple. Not being a farmer myself, I don’t know that much about barley, but I do know that it is a very sensitive grain, one that needs to be harvested at a precise moment; if that moment passes, the barley dies and the crop is lost. Hence, the counting of each day with great care and attention. Today, however, we are not harvesting any wheat or barley, and we don’t have the Temple, so why count? Where do we find meaning in this ritual? I want to suggest a few options.

Our lives are like the barley, sensitive and in need of great attention. Inside the tough, outer shell of the human body, our souls and spirits require love and devotion, a constant dedication of commitment to maintain a healthy life. We tend to focus on the body, exercising and eating right, getting enough sleep, taking vitamins and seeing the doctor. Yet, how many of us pay the same amount of attention, give the same amount of time and energy to our souls? Sefirat ha’omer offers us the chance to spend 49 days in direct contact with our souls on a daily basis, for each day that we count, we focus on a different aspect of our inner being.

Coming out of Mitzrayim (Egypt), we left the place of limitations and boundaries, a place that represents all forms of conformity and definition that restrain, inhibit or hamper our free movement and expression. Therefore, leaving Egypt is about embracing freedom from constraints. (Rabbi Simon Jacobson) The Omer invites us to count each day as a single unit of time, a unique period in our life that happens only once. What did today mean for you? Were you compassionate, disciplined, productive? Did you study, spend time doing something solely for yourself? Did you love someone today? Did you love yourself?

Each day has infinite value, infinite worth, infinite potential. We often overlook that idea in favor of greater periods of time: how was my week, my month, my year? Yet, hayom (today) is the most precious gift, for as the old adage goes, “today is a gift, which is why it’s called the present.” When we count each day, we don’t wait for greatness to come tomorrow or next week; when we count each day, we might find out how wonderful or painful, how rich or poor, how glorious or frustrating our lives truly are. If it is the positive, we can celebrate that. If it is the negative, we can recognize it and, hopefully, do something about it before it snowballs into something more major, more harmful.

This period of counting the Omer, these next several weeks, I invite you to tap into the power of life-affirmation through acknowledging time passing; mark the end of each day, before you go to sleep, by reviewing your day, seeing where you succeeded, achieved, produced, laughed, shared, gave, received. And, see where you could have done better, been nicer, kinder, who you may have hurt and who hurt you; ask for forgiveness and offer forgiveness. And then, with the spirit of our people, count the day.

As I have taught my kids, life is precious, each moment matters, the less we take for granted the better. As Shakespeare has Julius Caesar remind us, “Of all the wonders that I yet have heard, it seems most strange to me that men should fear; seeing that death, a necessary end, will come when it will come.” May we all live long, healthy and rich lives, and when that day arrives, when life in this world transitions to the next, may we have counted each of those days of life with as much fullness and fortitude as humanly possible.

Apr 14, 2014 | Email Newsletter Full Article, Meditation

By Rabbi Toba Spitzer

Passover is ultimately about freedom and new beginnings. The exodus from Egypt is a birth story – the birth of the Israelite people, and of a new kind of society, covenanted in love and justice. Passover is also a spring holiday, celebrating the first harvest and the new birth of the flocks. So part of the practice of clearing out hametz is linked to this sense of beginning, of new possibilities – clearing out the old, to make room for the new.

In many Hasidic interpretations, hametz is understood as internal obstacles and negativity, and we take this week of Passover to clear out as much of this as we can. So another possible focus is some kind of intentional “clearing out” of those internal tendencies – selfishness; greed; excessive pride; negativity towards self or others – that are getting in the way of our own liberation.

Rabbi Shefa Gold teaches:

“I’ve been experiencing “Matzah” as the essence that we must return to, must re-discover in order to grow in purity and awareness toward our liberation. The “hametz” is the sourness, often unconscious, the residue from suffering, disappointment. When hametz is left to its own, it causes inflation which is the process whereby layers of false-self build up to protect the essential core. The trouble is that through this process we also lose access to that essence. Before Pesach the challenge it seems to me is to release those layers of false self and then to discern the sourness that gave rise to that layering, then to re-experience the essence which is the unique spark at your core…”

For our sit, we’ll do an internal “bedikat hametz,” checking for internal hametz. When this is done traditionally, it’s playful – done with a candle and a feather. A gentle process, knowing full well that we’re going to find something – and appreciating it when we do find it, just like it’s fun to find the hametz that’s been stashed around the house for the evening inspection.

BEGIN SIT – settle in to seat, into physical sensation, breath.

Begin to notice the small the bits of “hametz” in our experience – that which keeps us from being present in this moment. It might be desire – wanting something to be happening outside of this actual moment of experience.

Or it might be aversion – pushing away some part of our experience that is unpleasant, that we wish wasn’t happening.

There might be judgment that arises – judgment of self, judgment of others.

There might be distraction – the mind seeking something more interesting than paying attention to what is.

Whatever arises, whatever obstacle you find to just being present – imagine you have a feather, and you gently, playfully, whisk it away. And then come back to the present moment of experience.

A desire arises – whisk!

Aversion arises – whisk!

Judgment arises – whisk!

And we do this with compassion, with an openness of heart. With each flick of the feather, a space opens up; there is a small movement towards freedom.

SIT

CLOSING: Noting the types of hametz that tend to arise, and setting a kavvanah, an intention, for this Pesach, to let go and release it. Not forcing, just setting an intention. The prohibition during Pesach is on owning any hametz – so let go of ownership. Understand that these inner obstacles are not you, do not belong to you, and you don’t belong to them.

Mar 27, 2014 | Email Newsletter Full Article

By Lisa Zbar

Up until recently, my runs haven’t been mindful, although they have been full of my mind.

They’ve taken one of two forms. Either I have been filled with innumerable, maybe even hundreds, of thoughts and feelings, in a full-body experience, without any observation or even curiosity—one might call it a running commentary. Or, I’ve gone into a vortex of near obsession about a situation or person.

Pleasant, don’t you think?

Here’s a glimpse of the stream of thoughts and observations from the first form:

I feel like lead

I want to turn around

I feel so loose!

That driver is a jerk

The sun on my face is a blessing

I’m underdressed

Now I’m overdressed

I wish I could run like she does

Bike riders scare me

I feel alive

The other form has asserted itself when I’ve felt wronged or seriously misunderstood. In these situations I’m like a child’s top. The thoughts are the string, controlling how I spin, whether I have control, and how fast I turn.

A recent, dramatic event led to a clear view of these two workings of mind.

I was hit by a Suburban last summer and couldn’t run as various body parts needed to heal. I didn’t plan it this way, but I started to focus on my meditation practice. I’m grateful to be able to report that it has deepened and expanded, something I do every morning for 20 minutes, preceded by a few minutes of reading. I read Buddhist sources, commentaries on the psalms, basic texts on mindfulness and meditation practice, and Jewish texts in spirituality. (I struggle to avoid “skimming” the New York Times.)

Just in the past month or two I’ve started to run again and my relationship to my mind is different. I am more mindful, it seems.

A couple of weeks ago I was in the park and got to thinking about a person whose words and behavior had hurt my feelings. I was really going at it, developing a miserable, laser-like focus on this situation.

After a half mile of this, I asked myself, “What is going on here?” Just that moment of stepping back showed me that I was sad, and scared that the situation wouldn’t change. I entered the fear and sadness, started to cry, and found some compassion for both of us.

As for the version of mind that is a running commentary, I now feel less that I am that litany of I hate this-I’m too hot-I’m too cold. I have distance, even a little humor, and can say to myself, “Look at all these reactions.” Mindfulness practice provides space between my thoughts and me, so that I am not what I think, even the glorious thoughts and sensations, that I wish would go on and on.

Mar 27, 2014 | Email Newsletter Full Article

By Rabbi Nathan Martin

Over the last few years I have turned my attention to growing summer vegetables. This project often starts in April with my attempts to cultivate early sprouts in the seed trays in our dining room (with dirt spills and all), and continues until the cool November frosts lay to bed the last of my tomato plants.

I take great pleasure in announcing, with fanfare, the elements of the summer’s dinner provided that day from one of my three garden plots. It is a great feeling to be feeding those I love with food that I have grown, harvested, and prepared. The process allows me to better understand the phrase from Psalm 90, “establish for us the work of our hands”

But there is an additional dimension of gardening that is deeply connected to my mindfulness practice. In my weekly sit on the cushion (I’m still working towards a daily practice) it doesn’t take long after settling in for me to become aware of the symphony of activity in my mind. I see myself working out numerous variations of conversations I plan to have later that day. I hear threads of music replaying themselves in a loop. And each time, I try as lovingly as I can to direct my attention back to the simple in and out of my breath. But gardening is different.

Sometimes, when my hands are working their way through the dirt, the stories and the music stop. I can spend long chunks of time simply digging, sifting, clearing with my mind relaxed and focused. It’s those moments when I realize that gardening can simply be another form of practice “off the mat.” It can be a chance for me to notice my breath, the warmth of the sun on my back, the feel of the dirt, the color and texture of the weeds, and ultimately the presence of that moment. After a particularly joyful weeding session I’ll even remember to thank the plants (out loud) for their generosity.