May 2, 2018 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

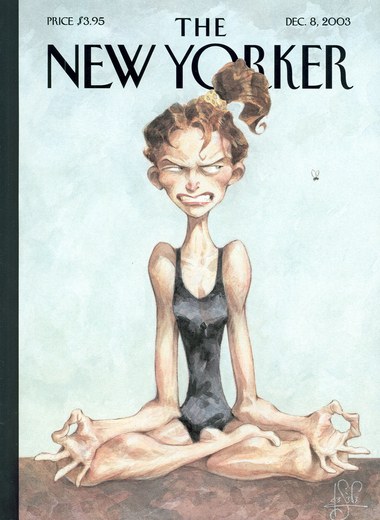

Several years ago, the New Yorker featured a cover that showed a woman sitting in the lotus position, ostensibly meditating. You can tell she is so wound up that she is about to jump out of her skin. If you look carefully in the direction of her baleful glare, there is a little fly, innocently tooling around.

Several years ago, the New Yorker featured a cover that showed a woman sitting in the lotus position, ostensibly meditating. You can tell she is so wound up that she is about to jump out of her skin. If you look carefully in the direction of her baleful glare, there is a little fly, innocently tooling around.

One of the reasons I find this image so funny is that I have been there myself so many times. I sit down to meditate or to pray with great zeal and focus – and then, something interrupts my plan. The drive I feel to engage in practice ends up eclipsing the practice itself; my focus shifts to how my plan was derailed and that I couldn’t meditate or pray as I (or my ego) wanted.

There is a seeming paradox between zeal and contemplation. Zeal is about acting now with a great sense of passion and confidence. Zeal is impatient, directed, quick. Contemplation, on the other hand, usually evokes “sitting with the issue” for a while. It is slow, receptive, internally oriented. How, then, can zerizut (zeal, alacrity) be a contemplative practice?

One answer might be one of my favorite teachings from Sholom Noach Berezovsky, also known by the title of his book, Netivot Shalom. “First comes effort,” he taught in multiple places. “Then comes a gift.”

When it comes to spiritual practice, it is important to draw upon our zeal. Zeal enhances our motivation, helps us overcome our inertia, commit to the effort. Spiritual practice is similar to going to the gym. It’s not enough to know about the benefits; you have to actually go to the gym before any transformation can take place. Zeal helps us make the effort and return to it again and again.

And then comes a gift. It’s not “the” gift; it’s “a” gift. We don’t actually know what will happen when we engage in practice. Sometimes we get distracted and annoyed. Sometimes it seems like nothing happens at all. And occasionally something very sweet and still and connecting opens within us. But whatever happens, whatever the experience is, is a gift.

So first the effort, and then a gift. When we stay focused on the effort, we can get so stressed by a small “failure” that we can forget why we are engaging in practice. But if we can lighten our grasp on the expectation created by our zeal and look up and see what is true in this moment, we can find our experience – whatever it is – to be rich and filled with grace. Or as the Irish poet, Galway Kinnell wrote:

Whatever happens. Whatever

what is is is what

I want. Only that. But that.

May 1, 2013 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

Recently, I had the opportunity to test out a pet theory of mine and to see if it held any water. I was excited and nervous: what if this whole idea just sounded nice in my head but didn’t have any traction on the ground?

For the past three years or so, I have been interested in the juxtaposition of justice work and contemplative practices. I had been leading a variety of service-learning trips, mostly with college students in the Global South, and also doing local volunteer work, helping a family of refugees from Burma start to make a new life for themselves in the US. I had also been teaching meditation. I wondered: could there be a connection between these two worlds?

Perhaps combining social justice with contemplative practice could help make sure that meditation and prayer and learning don’t turn into self-indulgent, self-satisfied activities that are only about personal fulfillment. And perhaps bringing contemplative practices to justice work could help ensure that activism is more creative, more sustainable and more grounded in the values it endeavors to hold.

At our Jewish Meditation Teacher Training retreat in November, I had the first opportunity to share some of my ideas and I was pleased with the positive reception. But in some ways, I felt like I was preaching to the proverbial choir. Many of the participants in the program are already involved in various forms of social change and all of them have a strong meditation practice. All I had to do was connect the dots.

But this winter I had the opportunity to be the scholar in residence for Repair the World’s Fellow program. This training was for twelve outstanding professionals who are leading service learning programs across the country. They came to the training without any a priori interest in contemplative practices. They were looking for tools to be more effective teachers, activists and organizers.

To my great delight, they got it right away. They understood that, in the words of Paul Auster, “the inner and the outer could not be separated except by doing great damage to the truth.” Paying attention to our inner lives – to what is difficult, to our own inner shadow, to the process of reflection – is the same thing as paying attention to the areas that need fixing out in the world, just on a different level. And bringing a loving, gentle awareness to the areas of brokenness, both inner and outer, can open possibilities of healing and transformation in beautiful and surprising ways.

This is just the beginning. Stay tuned for more…

Several years ago, the New Yorker featured a cover that showed a woman sitting in the lotus position, ostensibly meditating. You can tell she is so wound up that she is about to jump out of her skin. If you look carefully in the direction of her baleful glare, there is a little fly, innocently tooling around.

Several years ago, the New Yorker featured a cover that showed a woman sitting in the lotus position, ostensibly meditating. You can tell she is so wound up that she is about to jump out of her skin. If you look carefully in the direction of her baleful glare, there is a little fly, innocently tooling around.