Jul 26, 2024 | Blog, Rabbi Josh Feigelson, PhD, President & CEO, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

I will admit that I wasn’t prepared for the emotional response I experienced upon reading President Biden’s letter announcing his decision to turn down renomination this week. I was really moved. Upon reflection, what touched me most was the rarity of witnessing the most politically powerful person in the world acknowledge his limitations and, after some reluctance, ultimately volunteer an act of profound sacrifice for what he perceived to be the greater good. While I’m used to stories of sacrifice from soldiers, first responders, and even everyday people, this kind of story isn’t one most of us encounter frequently.

“Of all the rituals relevant to democracy, sacrifice is preeminent,” writes the contemporary political theorist Danielle Allen. “No democratic citizen, adult or child, escapes the necessity of losing out at some point in a public decision.” (Talking to Strangers: Anxieties of Citizenship since Brown v. Board of Education, 28) Allen notes that while it is essential that sacrifice be distributed equitably—that is, that one or a few groups not bear a disproportionate share of the burden of sacrifice—at bedrock, democratic life depends upon the willingness and capacity of every citizen, from the most humble to the most powerful, to be able to sacrifice their desires for the greater good. It happens every time the losing minority concedes a vote in a legislature or an election (something we have learned cannot be taken for granted). That, it seems to me, is one of the things Alexis de Tocqueville meant when he wrote about the habits of the heart necessary for democracy.

Such habits are fundamentally spiritual things. As the list of communal sacrifices in Parshat Pinchas reminds us (Numbers 28), sacrifice is central to the spiritual life described in the Torah. And while we do not bring animal sacrifices anymore, the gesture of sacrifice itself—the willingness to give up something we own, want, or even love for the sake of a greater good—remains central to our spiritual life today. It is what we practice through mindfully surrendering our workday lives over Shabbat, our wealth through tzedakah, our dietary desires through kashrut. The point of so many of the mitzvot is to condition us to the awareness that we are indeed part of something much larger than ourselves—and, by practicing them, to nurture within our hearts the ability to sacrifice for a greater good.

Just before the list of sacrifices, the Torah tells the story of the Jewish people’s first transition of power. “YHVH said to Moses, ‘Ascend these heights of Avarim and view the land the at I have given to the Israelite people. When you have seen it, you too shall be gathered to your kin, just as your brother Aaron.” Moses pleads with God to appoint a new leader, someone who “will go out before them and come in before them, who will take them out and bring them in.” God tells Moses to take Joshua and place his hands on him in front of all the people, and in doing so, to invest him with authority. And that’s what they do.

Commenting on Moses’s description of the leader as one who goes out before the people, Rashi, quoting the Midrash, elaborates: “Not as is the way of kings who sit at home and send their armies to battle, but as I, Moses, have done,” leading the people personally, with my own body on the line. At this profound moment of transition, Moses grounds the function and authority of leadership in the willingness of a leader to sacrifice through personal example—and, in so doing, to inspire meaningful, life-affirming sacrifice among their flock.

President Biden would probably be the first to say, “Don’t compare me to Moses.” I don’t mean to make him a saint (in any case, that’s the business of the Catholic Church). And I don’t mean to offer a political endorsement (in any case, he has taken himself out of the race). But in my lifetime, this is one of the more remarkable moments of leadership and sacrifice I have witnessed. No matter our political persuasions, I hope it can inspire in all of us an appreciation of the importance of the spiritual habits of the heart, and help renew within us the capacity and willingness to sacrifice for the greater good.

Jul 18, 2024 | Blog, Rabbi Josh Feigelson, PhD, President & CEO, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

A couple of friends sent me David Brooks’s column in the New York Times last Friday. While the headline made it seem that the column was about “Trump’s enduring appeal,” the column itself might more accurately be summarized as a reflection on, as Brooks put it, “the deeper roots of our current dysfunction.” As one of my friends said, they thought I might resonate with Brooks’s analysis, and especially his conclusion, that the “work of cultural repair will be done by religious progressives, by a new generation of leaders who will build a modern social gospel around love of neighbor and hospitality for the marginalized.”

They were right. I do like a lot about Brooks’s analysis, and I do resonate with his conclusion. I think that in many ways the work we do here at IJS is about laying the spiritual foundations, in both thought and practice, for “a Judaism we can believe in” (with apologies to Barack Obama), one that helps us to hold and navigate the tensions of self and other, neighbor and stranger, such that, as Parker Palmer puts it, our hearts break open rather than apart.

Last week I wrote about some of the anxieties I have been experiencing this summer in the current political climate, and about how I’ve been trying to both be aware of their roots within me and respond to them mindfully. The response to that reflection was unusually voluminous. It seemed to have struck a chord. And that was before the former president escaped assassination by a hair’s breadth. The anxiety has only increased.

What I find myself coming back to, what I think Brooks helpfully named, is that the challenge and the crisis is not something that will be solved quickly. It is generational. It is structural. Regardless of who the President is on January 20, the deeper challenges will remain. Brooks identifies two: 1) developing and agreeing on systems of government to provide meaningful representation in a postmodern era of technology and communication; and 2) filling the “void of meaning… a shared sense of right and wrong, a sense of purpose,” as he puts it. He leaves out some other biggies: Developing approaches to economic livelihood that do not depend on extracting and depleting natural resources; adapting to a less-hospitable climate; coming to some shared understanding about race and whether and how we want to continue to redress America’s original sin of slavery; continuing big questions about gender and sexuality; there are more.

These are not short-term projects, of course, and Brooks, it should go without saying, is not the first to talk about them. In the short-term, it seems a good bet that we will experience more collective turbulence, more emphasis on identity politics on both right and left, and more verbal and physical violence–especially at those who are perceived by a large group as “other” and therefore seem to impede calls for “unity.” (Jews know from this.) These tensions will continue to animate American political life, and American Jewish life too.

One of the reasons I believe our Torah at IJS is so potentially helpful for this moment is that it draws much of its inspiration from Hasidism. As I like to point out–and it still blows my own mind–Hasidism is an Enlightenment-era project. The Ba’al Shem Tov (1698-1760) and Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) were contemporaries. Yes, Hasidism happened in Eastern Europe, and thus wasn’t directly in the conversation about democracy happening in the West. But Hasidism responds to some similar questions as Enlightenment thinkers. The Enlightenment asked: How do we understand and organize our political lives when sovereignty is not exclusively concentrated in a king or emperor, but is instead shared among all citizens? Hasidism asked: How do we understand and organize our religious and spiritual lives when divinity is not exclusively concentrated in a Maimonidean unknowable unmoved mover, but is instead shared among all images of God and all of Creation?

Those questions led the Hasidic masters to articulate a theology that emphasizes the inherent dignity, uniqueness, and interconnection between all created beings. And they led Hasidism to develop both ecstatic and contemplative forms of spiritual practice, so that these ideas weren’t only intellectual assertions but actual ways of being in the world. (Unlike some Protestant traditions, however, they did not lead to democratic forms of deliberation and decision-making.) Our founders here at IJS were, thankfully, wise enough to recognize how much good such an approach can do in the world today.

This coming Tuesday on the Jewish calendar marks the Seventeenth of Tammuz, the beginning of the three week period leading to Tisha b’Av, known as bein hameitzarim, or the time of constriction. Over that span we become increasingly pulled into the orbit of despair that characterizes the saddest day of the year, the day when the Temple was destroyed and the Divine went into exile along with the Jewish people. Yet Jewish history is nothing if not the story, told again and again, of resilience and renewal in the face of hardship. As we enter into that orbit this year, I find myself breathing deeply–not only in an effort to stay calm and open, but also to tap into the deep spiritual roots of our people and our tradition. It is the sorcerer Balaam who, in this week’s Torah portion, reminds us that we have everything we need: “How good are your tents, O Jacob, your divine dwelling places, O Israel.” (Num. 24:5)

It is a long journey. It always has been. And we are still on it together.

Jul 11, 2024 | Blog, Rabbi Josh Feigelson, PhD, President & CEO, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

This isn’t a political space and I don’t intend to make it one here. But I also feel a need to talk about politics this week. Wish me luck.

For the last couple of weeks I’ve been experiencing a deep feeling of unease. I have found it hard to focus. I’m more easily distracted than usual. My sleep hasn’t been as good. And it’s not about anything in my personal life–everyone is more or less okay, thank God–or even, at this point, having to do with the situation in the Middle East, which we’ve been living with for too many months.

No, the source of my anxiety is pretty clearly the combined effect of some enormously significant Supreme Court rulings at the end of June and the national conversation that has erupted in the last two weeks around President Biden’s aging and his fitness as both a candidate and holder of his office.

When I sit with it, I find that my anxiety seems to be primarily rooted in both the instability of this moment itself, the prospect of instability in the future, and the powerlessness I experience of living with that instability. It feels like the earth is quaking beneath my feet and there is precious little I can do about it.

The thing is, of course, that that’s not really news–certainly not for many people in the world. While I happen to have been born into a set of conditions that has allowed me to presume a lot of stability (privileges both earned and, probably more often, unearned), so many other people have had a different, more precarious, experience. But this is happening to me now. So here I am, living with my experience.

Again, when I sit with it, I find that what I first really seem to want is just that basic stability. It was so much easier when I felt like I could rely on the idea that some things were settled, that there were big rocks to stand on. In the absence of those big rocks, I sense an impulse–a perfectly natural impulse–to find some other terra firma on which to rest. My mind starts spinning stories about what will happen. Even if they’re unhappy, negative stories, at least they’re rocks.

Chukat is a Torah portion about death and transition. In this Torah portion we read of the deaths of Miriam and Aaron and the transition of the High Priesthood to Aaron’s son, Elazar. Moses, likewise, learns that he will not enter the Promised Land, even as the Israelites make their way to its borders. The times, they are a-changin’: big rocks crumble, uncertainty abounds.

A counterpoint to that uncertainty is the opening section of Chukat, the law of the red heifer, which responds to the destabilizing reality of death through purification. “This is the ritual law that YHVH has commanded,” the Torah says: “Instruct the Israelite people to bring you a red cow without blemish, in which there is no defect and on which no yoke has been laid.”

Why a counterpoint to instability? On one level, because of its simple assertion: As the midrash notes, this is a “chok,” a law without reason (unlike, for instance, the commandment not to steal). Performing it is thus an expression of faith, an affirmation that we do some things because of our commitment.

But I think it’s deeper than that. Rashi, based on the Midrash, suggests that the entire ritual is tikkun, a repair, for the sin of the Golden Calf: “Since they became impure by a calf, let its mother (a cow) come and atone for the calf.” And the impulse to erect the Golden Calf was itself rooted in the dis-ease of living with the unknown: “Come, make us a god who shall go before us,” the people said, “for that fellow Moses—the man who brought us from the land of Egypt—we do not know what has happened to him” (Exodus 32:1). The people’s discomfort at not knowing, their fear of living with uncertainty, prompts them to yearn for something solid: an idol.

We do not perform the ritual of the Red Heifer today, we only read about it. Yet I find that it speaks to me at moments of profound uncertainty, like this one. For me, it’s a reminder to be mindful of how I respond to the very human impulse for stability, to be careful in where I invest that yearning, to be wary of seductive solutions. Because in truth, instability is ever-present. The sands are always shifting beneath our feet–sometimes quicker and more visibly, sometimes slower and less obviously. The Red Heifer is an invitation to live with awareness of that instability, and to respond to it with wisdom, expansiveness, and compassion.

Jun 27, 2024 | Blog, Rabbi Josh Feigelson, PhD, President & CEO, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

In the weeks before he left for camp, my youngest son, Toby, and I started watching the sitcom “Modern Family” together. It has been a delight to rediscover this show that I remember being stupendously funny the first time around and to share it with my kid now. (It’s also really interesting to see which parts of the show hold up 15 years later and which ones could use a rewrite.)

Like any good family-oriented sitcom, one of the things that makes “Modern Family” work is the way it reflects the real-life dynamics of so many families. And indeed that’s kind of the main point of the show: Parent-child relationships–of both little kids and grown children–seem to have some predictable characteristics across families no matter how they’re configured. So many people from so many different backgrounds could watch “Modern Family” and find themselves laughing because they could see themselves reflected in what they saw on the screen.

There’s a particular episode from one of the early seasons in which one of the sets of parents, Phil and Claire, find a burn mark on the couch just before Christmas. Because it’s about the width of a cigarette, they immediately conclude that one of their children must have been smoking. They sit the kids down and Phil rushes into an ultimatum: Confess, or we’re not having Christmas this year. None the kids owns up, and Phil, in a way that skirts the bounds between firmness and violence, starts dismantling the Christmas tree.

The episode continues from there, with the parents ratcheting up the pressure and the kids trying to figure out whether to confess to a crime that it increasingly becomes clear they didn’t commit. For me as a parent, what was so painfully recognizable was the conversation between Phil and Claire in which they acknowledge they (well, really Phil) moved too quickly to DEFCON 1–but then wonder about whether to back down. Their basic calculus is this: “If we back down now, the kids will never believe any threat of consequences again in the future.” So they stick to their guns despite their better judgment. (If you want the spoiler to the mystery: It turns out, of course, that it wasn’t a cigarette burn at all but rather a burn caused by the sun refracted through the star on top of the Christmas tree.)

I hear echoes of this all-too-familiar dynamic in Moses’s dialogue with God after the incident of the spies. In this case, of course, the kids really did mess up: after the spies return their worrisome report about the Promised Land, the people’s deflation turns to rebelliousness, despite the encouragement of Joshua and Caleb. God’s instinct is to start over: “I will strike them with pestilence and disown them, and I will make of you a nation far more numerous than they!” (Num. 14:12) But Moses, as he did previously after the sin of the Golden Calf, reminds God that there’s a political dimension to this conversation: The Egyptians will hear that, despite all of God’s great power, God still couldn’t manage to get the Israelites safely to Canaan. So wiping them out would be a bad move.

But Moses, acting here, as it were, as God’s rabbi, also recognizes the bind that God is in–and points God to an off-ramp. He reminds God of God’s own words: God’s attributes of mercy, patience, and forgiveness that the Holy One originally proclaimed during the Golden Calf episode. And he invites the Holy One to live up to that greatness: “And now, let your power be great… pardon the iniquity of this people, according to the greatness of your loving kindness, just as you have been bearing it for this people from Egypt until now.” (Num. 14:17-19)

God, of course, relents and comes up with a different solution–perhaps the solution that needed to be invoked all along: more time. This generation simply wasn’t ready to manage the transition from Egypt to Canaan. God’s expectations were simply too high. So, change plans: the people will need to wander in the desert for 40 years until a new generation can arise, one that is in better condition to enter the Promised Land.

There are, of course, potential lessons to be inferred about wars and politics from this episode. (Several years ago I published an article, drawn from my dissertation research, about Rabbi Yitz Greenberg’s testimony to the Senate Foreign Relations committee regarding the war in Vietnam. The lessons he draws are evocative of this story.)

But we encounter the truth of this story on a day to day and even moment to moment level: certainly for those of us who are parents, but truly for all of us who are in any kind of relationship that experiences hope and expectation, the subversion of those hopes or expectations, and the choice we confront of what to do about it. One of the things the Torah seems to be saying here is that all of us, even the Holy Blessed One, experience frustration, anger, resentment. And all of us can make rash decisions and proclamations on the basis of those strong emotions. Those decisions are rarely the best ones, but we can wind up in what feels like a cul-de-sac looking for a way out.

The good news, the Torah teaches us, is that, like the Divine, we images of the divine also have the power of hesed within us. We, too, can activate that power. Likely that activation will be aided by the help of a friend, a coach, a clergyperson. But we have the power within us to act in ways that are more loving, generous, and forgiving. From prayer to Torah study to Shabbat to Yom Kippur–which re-enacts the forgiveness after the Golden Calf and this forgiveness after the spies–our spiritual practices are regular opportunities to develop and strengthen these muscles of hesed.

Jun 20, 2024 | Blog, Rabbi Josh Feigelson, PhD, President & CEO, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

A memory came up on Facebook the other day: a picture of a note from our youngest child three years ago after he arrived on the bus for his first experience as a camper at Camp Ramah in Wisconsin. It was brief, but it made my heart melt: “I’m having so much fun! Toby.”

Summer camp is a multigenerational through line in my family history. My grandfather went to Camp Tonkawa with the Boy Scouts in Minnesota a century ago. My parents met while working on staff at Camp Tamarack in southeastern Michigan. I went to Camp Ramah in Canada, Interlochen Arts Camp, and Wright’s Lake Scout Camp as a kid. And beginning when our first-born was old enough to attend as a camper, Natalie and/or I have sung for our supper by working on the staff at Camp Ramah in Wisconsin–and our older kids have gone on to be counselors there too. Camp is a basic fact of life for us.

So this week marked something of our annual celebration, as the kids went off to camp again.

The report from our middle child, serving his first full summer on staff, is that the initial couple of days were hard–storming, norming, forming, as the old saying goes–but that his cabin is coming together. Because, of course, there is so much that goes into creating this community every year. Every camper and every staff member arrives at camp with a world of expectations, hopes, fears, joys, and anxieties, and they ultimately have to find a way to live together.

And what we witness year after year is that eventually, most of the time, they do. With patience, openness, honesty, care, love–and with shared projects to work on, shared songs to sing, shared dances to dance together, shared natural beauty to bask in–a disparate group of hundreds of young people becomes a community. For so many people, camp is a place where, as much as anywhere on earth, they experience not just community, but an awareness of the shechina, the divine presence.

There’s a short passage in Parashat Behaalotcha that has always fascinated me, Numbers 9:15-23. In poetic and, for the Torah, repetitious language, it describes how the attunement between the Israelites and the divine presence. It could be summarized simply by verse 18: “At YHVH’s command the Israelites broke camp, and at YHVH’s command they made camp: they remained encamped as long as the cloud dwelled over the mishkan.”

Among the many meaningful elements of this short passage is the repeated use of the words yachanu, “they camped,” and yishkon, “God dwelled.” By my count, camping is referenced six times (and mirrored by linsoa, journeying–the opposite of camping) while dwelling is mentioned ten times, including the mentions of the mishkan itself, the place of divine indwelling. Given that the Torah is normally quite economical in its prose, an efflorescence like this is an invitation to interpret.

Perhaps an interpretation can be found in another phrase that recurs in this passage over and over: “al pi YHVH,” by the word of the Ineffable One. During their time in the wilderness, the Israelites would break camp and make camp repeatedly. And according to this passage, each time they made camp, the divine presence would come to rest in their midst–until the divine gestured to them that it was time to move again. What the passage describes is a profound attunement–between the collective, its constituent individuals, and the divine presence.

It is, perhaps, an ideal (notably, the first time the root SH-K-N is used in the Torah comes in Genesis 3:24: “the Divine stationed [vayashken] two cherubs east of Eden” after human beings were sent out from the Garden of Eden). And it may feel particularly far away these days, this vision of sacred attunement on not only a personal, but a collective level.

Yet I think there’s a reason why so many Jews keep coming back to camp year after year. It isn’t only because, as my young son wrote, camp is so much fun. As anyone who has been to camp knows, camp isn’t always fun. But the process of making a community, of living in greater harmony with the rhythms of nature and the rhythms of Jewish life, of singing and praying and studying and dancing together, of negotiating relationships and learning how to live peacefully in community with one another–in all of that messy and beautiful work of making camp, we make a space to recognize the divine presence. For many people, camp is a place where we experience the attunement that is always possible–but that is uniquely available under the trees, by the lake, and around the campfire.

Jun 11, 2024 | Blog, by Rabbi Miriam Margles, Senior Core Faculty, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

Each time we take the Torah out of the ark in synagogue, chanting its verses in community, we are reenacting revelation at Mount Sinai. Though not nearly as dramatic as the Torah’s description of fire and smoke, thunder and lightning, a quaking mountain and a shofar blast growing louder and louder, our rituals of standing up on our feet as the ark is opened, witnessing as the scrolls are revealed, and bringing the Torah from the “mountain” of the raised bimah into the midst of all those gathered, enable us to evoke Sinai in the present moment.

On Shavuot (the festival celebrating the giving of the Torah, which begins this year in the evening of June 11th), we seek to inhabit the experience of Sinai even more fully as the very scene of revelation is read from the Torah, surrounding us with the images of flashing fire and the voice of God rumbling through the chanted Ten Commandments. On Shavuot, we seek to be present not only as witnesses to the powerful experience of the giving of the Torah, but to join our ancient Israelite kin in actively receiving Torah and opening ourselves to receive Divine Presence.

But in the biblical description of Matan Torah (the giving of the Torah) there is a disruption in the Israelites’ receptivity. Although they collectively call out “All that YHVH has spoken we shall do!”, actively taking hold of the commitment to live their lives in alignment with Divine will and sacred practice, at the very moment of direct Divine encounter, the Israelites sever connection. They become so gripped by fear, afraid that they will die if they remain present to the unfolding revelation, that they ‘stand at a distance.’ They plead with Moses to interrupt this intimate intensity and ask him to be their flesh and blood, familiar, human-scale intermediary.

I feel the loss that this reaction created. In the face of such potent, available closeness, the Israelites created distance. With Shavuot’s invitation to embody revelation, an approach of mindful spiritual practice invites us to both inhabit the deepest wisdom of our ancestors’ experience, as well as learning from and bringing tikkun/repair to our ancestors’ limitations. We can turn our attention to explore the question for ourselves – when does fear cause you to distance yourself from that which is intimate, sacred, powerful and true?

Revelation in its varied forms can be unsettling and stir fear. As Rabbi Gordon Tucker writes the embodiment of revelation “should cause us to tremble.” It “should penetrate one’s entire person, one’s entire body.” Whether in the close, revealing presence of another person, in a breathless, awe-opening moment in nature, in an unmasking and emptying experience of solitude or in prayerful surrender, the ego-gripped self can’t help but loosen. In such experiences, we get a glimpse of Divine reality – more vast and far more intimate in its awareness than the small self that we know, tethered to the comfort, stability and safety of its self-enclosure. It can be frightening to release the protective grasp on our sense of self. It can be frightening to feel all that this demands of us – holding us in the commitment to show up again and again – enlivened, open and connected – not retreating back into a contracted way of being, not going back to sleep.

In the liturgy of the Torah service, there is guidance to practice meeting the fears that revelation’s intimacy stirs. And while these words are part of every Torah service, I want to engage with them as a practice particularly for Shavuot:

Just before Torah reading begins, as the first person is called up to the Torah for an aliyah, the gabbai recites, “May Divine Presence help, protect and save all who trust in You…” And the community responds – “Ve’atem ha’dvekim b’YHVH Eloheykhem chayyim kulkhem hayom/You who cling to YHVH your God, are all alive today.”

First we are invited to consciously root ourselves in the qualities of Divine protection and support, present in our bodies, souls and breath, present in community, present in the ancestral strength and love that reverberate through us and through prayer, ritual and Torah. When we take these few words as instructions, we practice leaning into trust and the power that saves us and holds us. Then the community responds together by consciously, deliberately, drawing close. In our voices and our presence with one another, we mirror to each other that which is true – “You who are dvekim” – you who keep moving closer, who attach yourselves to Limitless Presence, who cling to intimate connection even when you are afraid – you are alive today! As we stand together at the foot of Sinai, ready to receive living, breathing, ever-unfolding revelation, we have the opportunity to repair the distance that fear can engender. We practice becoming dvekim, those who choose to consciously, lovingly, bravely draw close.

Chag same’ach!

Jun 11, 2024 | Blog, by Rabbi Sam Feinsmith, Senior Core Faculty, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

According to the Torah (Exodus 19), the Jewish people perceive the Divine Voice amidst a loud cacophony of thunder, lighting, and quaking ground. But I Kings (chapter 19) offers a different model of receiving revelation: the prophet Elijah experiences the Voice not in the tumult of wind, fire, or earthquake, but rather in a kol demamah dakah, the “still, small voice” – a practice each of us can emulate as we move towards the holiday of Shavuot, the holiday commemorating the revelation of the Ten Commandments at Sinai

Join IJS Senior Core Faculty member Rabbi Sam Feinsmith for a short meditation on listening for the kol demamah dakah, the “still, small voice” of the Divine, which we can perceive when we are able to cultivate a state of external and internal stillness.

Click Here to Practice with Rabbi Sam Feinsmith

This short meditation is excerpted from a longer teaching Rabbi Feinsmith offered in the days leading up to Shavuot in 2021 – one of a series of five consecutive sessions he led on “Standing (or Sitting!) at Sinai, Here and Now” on the IJS Daily Sit. Click here for the source sheet Rabbi Feinsmith created for the session.

For the complete teaching and practice, click here; for the full YouTube playlist for this five session series, click here.

Jun 6, 2024 | Blog, Rabbi Josh Feigelson, PhD, President & CEO, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

Peter Salovey, who is stepping down this month as president of my alma mater, Yale University, was my freshman psychology teacher thirty years ago. The course was popular. Hundreds of students took it.

Salovey was always quick with a joke. Before the final, I remember him telling us the story of a huge lecture hall full of students writing their exams, much like the one we were about to take. As time is winding down, a handful of students are finishing up. “Ten minutes left,” the professor calls out. A few finish and hand in their exam books. “Five minutes.” More finish. “One minute.” At this point, a single student is the last one writing–and he’s still going at a feverish pace.

“Time’s up, pencils down,” the professor calls. The student is still writing.

The professor shrugs, picks up the pile of exam books, and starts heading to the door. As she passes the student she says, “Last chance.” Still writing. The professor walks to the door of the lecture hall and the student races up to her. “Sorry,” she says, “you missed your chance.”

“Do you know who I am?” the student asks.

“What do you mean, do you know who I am?” the professor responds. “You went beyond time.”

“Do you know who I am?” the student asks again, more stridently.

“Look kid, I don’t care who your parents are or how important you think you are–the same rules apply to everyone.”

“Do you know who I am?” the student asks one more time.

“No,” she says.

At that, the student lifts up the pile of exam books in the professor’s arms, stuffs his in the middle of it, and races out of the room before she can figure out which exam book was his.

Professor Salovey told this story to ease some tension in the room before our final exam, but of course it reflects a deeper truth: We can often find ourselves in big, bureaucratic systems that render us nameless and faceless. And while those systems can sometimes provide advantages, they can also come at a cost. The advantages can include economies of scale, providing many more people access to valuable knowledge and experiences at an affordable rate. The disadvantages can include a lack of intimacy, a thinning of communal bonds, and ultimately both the capacity for and willingness to engage in abuse of the system.

The Book of Numbers, which we begin reading this week, marks an inflection point in the Torah. It is a book of generational transition, as the generation of the exodus dies out and the next generations come of age. And, with its multiple countings of the Israelites, the feeling tone of the more intimate stories of Genesis and at least early Exodus finally and fully gives way to a much larger, more corporate sense of a nation ready to assume the responsibilities of self-governance in the promised land.

Instructing Moses to take a census, the Holy One uses a fascinating phrase: Moses is not to count the people simply according to their number, but instead b’mispar shemot, the “number of their names” (Num. 1:2). The 16th century Italian commentator Rabbi Ovadiah Sforno observes that this unusual formulation suggests “the names of the individuals reflected their specific individuality, in recognition of their individual virtues.” This census simultaneously took cognizance of both the numerical scope of the people and each person’s uniqueness–an unusual kind of counting.

There would seem to be a connection between this kind of counting and the counting we do in mindfulness practice: Not simply logging minutes of practice, but aiming to be aware and attentive in each moment as it arises, present to the uniqueness of this particular time, place, and experience. That kind of practice can help us see our lives and those of other beings more fully. It can help us to humanize other people, avoid instrumentalizing them or relating to them as numbers without names–but instead to live with the awareness that every person has a name and a story. As so many forces in our world push us toward namelessness, facelessness, and dehumanization, this is a teaching we need to learn and practice again and again.

May 30, 2024 | Blog, Rabbi Josh Feigelson, PhD, President & CEO, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

On my podcast this week, I shared a bit about my recent struggle to walk our dog, Phoebe, in the midst of all the cicadas that now line the sidewalks of our neighborhood. (Folks, the cicada invasion is real, and it’s here, at least in Illinois.) While it’s okay for her to eat a number of them, too many could cause her to have stomach issues.

We’ve tried a muzzle (she hated it and got it off). We’ve tried the cone of shame (she outsmarted it). So where we’re at now is that I just have to hold the leash pretty tight when we’re walking, and I kind of yank her every time we approach a cicada. It seems to be working alright, but it makes for an unpleasant walk for her and a tired arm for me. But so far, so good: No major digestive issues to speak of, just a dog who is very eager to go in the backyard as much as possible (where there are many more cicadas).

I’m finding that, in its own way, the whole episode reflects a lot about the relationship my family and I have with Torah and Jewish mindfulness. First and foremost, we take the health of this creature of ours seriously. “V’chai bahem–v’lo yamutu,” as the Talmud comments on Leviticus 18:5: The Torah is meant to be lived by and not died by. (The interpretation is offered as a proof that we violate almost every prohibition in the Torah to save a human life.) So we approach the question of what to do about Phoebe and the cicadas with the value that her life matters. (The cicadas’ lives matter too, but… priorities. And common sense.)

Further, we’ve approached this question in a way that also asks about what is doable and practical. Can we completely shield Phoebe from the cicadas, just leaving her inside? No, that would harm other parts of her health and wellbeing–and ours! Could we create or buy some kind of robotic device that would walk ahead of us and vacuum up the sidewalk in advance? (Note to the Roomba people: This idea has potential. You heard it here first.) Again: impractical, cost prohibitive. As my teacher Rabbi Yitz Greenberg observes, God’s covenants with the world and the Jewish people are intended to operate on a human scale and pace–in ways that are achievable. So we’re looking for solutions that have some chance of implementation.

The basic motivating impulse here is to find a solution, to literally walk our talk. We espouse and hold dear some extraordinary values–honoring and sanctifying life, enabling the divine presence to be made manifest in the world in every action, every step. So, like our tradition, we take the ethical and practical questions seriously. That, in a nutshell, is halakha–often translated as “Jewish law,” but perhaps more fully and even literally rendered as “the way Jews walk in the world” (halakha which comes from the same root as the verb lalekhet, to walk).

A couple weeks ago I read a poem in The New Yorker by Ocean Vuong called “Theology.” It contained this line:

I thought gravity was a law, which meant it could be broken.

But it’s more like a language. Once you’re in it

you never get out.

Vuong’s words have been ringing in my ears since because I think they capture this challenge of understanding halakha so well: While at one point in my life I related to it as law–imposed by some external force, operating under the threat of punishment–as I’ve gotten older it has become much more like a language, operating in a more fluid zone of culture, explicitly and implicitly negotiated meanings, intertextualities and connections. It still has to make sense–languages have to make sense–but as language, halakha has a great deal more expressiveness and suppleness than when it’s understood only as law.

Concluding the halakha-rich book of Leviticus, Parashat Bechukotai begins with the words “If you walk in my ways.” Commenting a little later on the verse, “I will walk in your midst: I will be your God, and you shall be My people” (Lev. 26:12), Rashi picks up on the linguistic connection to the primordial image of the Divine walking in the Garden of Eden (Genesis 3:8) and interprets: “I will, as it were, walk with you in the Garden of Eden as though I were one of you, and you will not be frightened of Me.”

That’s the goal and the promise of our halakha: If we can act in the world in ways that are mindful, aligned with the covenantal values of the Torah, compassionate, present, loving, and attentive, then we reveal the Divine presence that is here walking with us. We discover that this world can indeed–even now–be a redeemed Eden. That’s what it’s really all about, even and perhaps especially when the obstacles to sensing that possibility are greatest.

Every Friday morning, IJS President & CEO Rabbi Josh Feigelson shares a short reflection on the week in preparation for Shabbat. Josh weaves together personal experience, mindfulness practice, and teachings from the weekly Torah portion in a uniquely accessible and powerful way. Sign up to receive Josh’s weekly reflections here.

May 24, 2024 | Blog, Rabbi Josh Feigelson, PhD, President & CEO, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

The last couple of weeks have been one of those moments when I pinch myself and ask, “Really, I get paid to do this?!” Because over the last two weeks, I have spent a total of eight days on IJS retreats–first for our Sustainers Circle and, this week, for our staff, both of which are extraordinary groups of people. My days have been filled with reflection, thoughtful conversation, study, and a lot of laughter–all things that I dreamed 25 years ago would describe the work I would do as a rabbi. It’s an extraordinary blessing and privilege.

We held both of these retreats at Trinity Retreat Center, a beautiful place on the Housatonic River in northwest Connecticut. IJS has a long history with Trinity–it’s among the retreat centers we regularly go to. The staff is extraordinarily welcoming. They eagerly accommodate our requests about kashrut and Shabbat. On a retreat last October for our Kol Dodi program, the Episcopal priest at the center, Rev. Dr. Mark Bozzuti-Jones, welcomed our group and spoke movingly about how important it was for him to welcome us because of the pain he knew our people were in after the massacre of October 7. There were tears.

During our staff retreat this week, my colleague Rabbi Myriam Klotz led a session on sacred listening, an area we’re really developing at IJS. The essence of sacred listening is practicing a form of mindfulness that’s relational: sitting with another person with presence and intention, giving them your full attention, being aware of what arises within you as you listen and making the mindful choice to continue listening non-judgmentally. In the session Myriam led, we each sat with a partner for three minutes and listened to them speak. At the end of those three minutes, we summarized–without editorializing–what they said. For the listener, it’s hard work to listen in that way without forming judgments or thinking about what to say. For the speaker, it’s usually a gift to feel heard and acknowledged. (Important side note: I’ll actually be teaching an online course on sacred listening with Myriam and Rebecca Schisler beginning June 23. You can register here.)

The speaking prompt in this exercise was Ayeka, Where are you?, in a spiritual sense. When it was my turn, what I found arising for me were questions about at-homeness. I noticed the feeling I experienced of being at Trinity: an exceptionally welcome guest–but also not at home in quite the same way I do on retreats at Jewish retreat centers. I perceived sensations having to do with translating our language and practices–acts which I find both exciting and also, in some cases, a little tiring. I observed how subtle these sensations could be: not categorical statements, but little movements in my mind, heart, and body. And I found those sensations pinging deeper registers of at-homeness and guestness in my life, most significantly in relation to Israel and America, the tonic and dominant chords of this key in my life.

“When you enter the land,” God tells the Israelites at the beginning of parashat Behar, “the land shall observe a Shabbat to YHVH.” From there the Torah elaborates the practice of the Sabbatical year, the paradigmatic case of a mitzvah that is observed only in the land of Israel. While the agricultural and economic practices associated with the Sabbatical year have deep spiritual meaning, and have even been adopted voluntarily by some Diaspora Jewish farmers in recent years, in halakhic or Jewish legal terms, they do not apply outside the Holy Land.

It’s one of the phenomenal features of Jewish life: We have significant practices that, for the centuries and millennia of our Diaspora experience, a majority of Jews experienced only in their imaginations, not their bodies. And it’s one of the amazing features of the Jewish people’s mass return to the land of Israel in recent centuries: the widespread reclamation and renewal of these ancient practices, not only in our imaginations, but in our bodies and on the earth.

Teaching in the eastern Europe of the 18th century, the Ba’al Shem Tov interpreted this opening line of Behar as referring not (only) to the Land of Israel, but to the body: “‘The land shall keep a Sabbath to YHVH:’ This means to bring rest and relaxation to the land, which is the body, and to rejoice over physical pleasures. Through this, the soul can rejoice spiritually. This is ‘a Sabbath to YHVH,’ for you need both these aspects on the Shabbat.” (Toldot Yaakov Yosef Behar) As happens frequently in Hasidut, the Besh”t here excavates the spiritual dimensions of the mitzvah alongside its physical ones. The Shabbat of the land becomes not only a legal or physical requirement for the land, but an invitation to a spiritual consciousness we can cultivate all the time.

Which brings us back to the question of at-homeness and guestness. Our spirituality is our capacity to experience being deeply, profoundly at home in the world. That is tied up with large, tectonic questions of place and culture: the ability not to have to translate; the sense that we are really in our place and with our people. But/and, that at-homeness takes place on a very intimate level at the same time, in the space of our minds, hearts, and bodies. Shabbat and the Sabbatical Year–our built-in Jewish retreats–are our regular invitations to sense that we and the Holy One are not guests in the world, but are, together, deeply and profoundly at home with one another.

Every Friday morning, IJS President & CEO Rabbi Josh Feigelson shares a short reflection on the week in preparation for Shabbat. Josh weaves together personal experience, mindfulness practice, and teachings from the weekly Torah portion in a uniquely accessible and powerful way. Sign up to receive Josh’s weekly reflections here.

May 16, 2024 | Blog

We are grateful to Rabbi Sharon Brous for speaking with IJS President & CEO, Rabbi Josh Feigelson! Please enjoy the conversation recording below.

Rabbi Sharon Brous is the senior and founding rabbi of IKAR, a Jewish community that launched in 2004 to reinvigorate Jewish practice and inspire people of faith to reclaim a soulful, justice-driven voice. Her 2016 TED talk, “Reclaiming Religion,” has been viewed by more than 1.5 million people. In 2013, Brous blessed President Obama and Vice President Biden at the Inaugural National Prayer Service, and in 2021 returned to bless President Biden and Vice President Harris, and then led the White House Passover Seder with Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff. She was named #1 on the Newsweek/The Daily Beast list of most influential Rabbis in America, and has been recognized by The Forward and Jerusalem Post as one of the fifty most influential Jews. Brous is in the inaugural cohort of Auburn Seminary‘s Senior Fellows program, sits on the faculty of REBOOT, and serves on the International Council of the New Israel Fund and national steering committee for the Poor People’s Campaign.

Her new book, The Amen Effect: Ancient Wisdom to Heal Our Hearts and Mend Our Broken World, is out now from Penguin Random House. A graduate of Columbia University, she was ordained by the Jewish Theological Seminary and lives in Los Angeles with her husband and three children.

May 16, 2024 | Blog, Rabbi Josh Feigelson, PhD, President & CEO, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

I want to tell you about my amazing Shabbat last week.

It came on the third day of a five-day retreat we held for about 25 members of our IJS Sustainers Circle, a group composed of former board members, alumni of our Kivvun program, and major donors. The retreat was full of meditation sessions, rich and musical prayer tefilah (prayer), mindful movement, mindful eating, and a lot of love.

But Shabbos took it to a whole different level.

And there was one moment that stood out in particular. It came as we were starting Shabbat dinner on Friday night. My dear friend and colleague, Rabbi Miriam Margles, reminded us all that this time is traditionally one of bracha, blessing. In my own home, as in many others, it’s a moment when parents offer blessings to their children. So Miriam invited us into this opportunity for blessing, but–this was an IJS retreat, so, of course–to do it perhaps a little differently than we usually do. We were to turn to a neighbor and look into their face. Each of us would share, honestly and from the heart, the blessing we needed just then. Our partner would listen attentively and then offer that blessing to us.

My partner was another member of the retreat faculty, the wonderful Rabbi Jonathan Kligler. And in this moment, I was able to look at Jonathan, be held by the embrace of his face, and share with him very openly the bracha I felt like I needed in that moment. Jonathan took my hand and offered exactly that blessing. And then I did the same for him. I know we weren’t the only pair in which tears were shed. It was a deeply moving experience.

It is always a profound thing to be seen and heard deeply like this. Being fully present with someone else, offering and receiving blessing–it felt as if, for that moment, we were like the two keruvim, the two cherubs that faced one another atop the holy ark. The Divine presence was revealed within us and between us. And that was happening all around the room.

But what also enabled that moment to be so meaningful was its ritual element: It took place at Shabbos dinner. It drew power from our mutual submission to and upholding of the rhythms of Jewish time. While in theory this showing up for one another, this “presencing,” could have taken place anywhere and anytime, in practice our ritual made it both more accessible and richer than it would have been otherwise.

Parashat Emor (Leviticus 21-24) details the holiday calendar: “These are My fixed times, the fixed times of YHVH, that you shall proclaim as sacred occasions” (Lev. 23:2). Beginning with Shabbat, the parasha goes on to enumerate the pilgrimage festivals of Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot, the counting of the Omer, and the holidays of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

Opening his commentary on this passage, the 13th century Spanish commentator Ramban (Nachmanides) observes that, while much of Leviticus is directed specifically to the priests, this passage is meant to be shared with the entire people. Why? “The priests have no greater duties with regard to the festivals than the Israelites, therefore the Holy One did not admonish Aaron and his sons in this section, but the children of Israel, a term which includes all of them together.” All of us, Ramban suggests, regardless of background or station, have a share in these times; all of us can access them; all of us uphold them. These are not special rites of professional ritualists; they are the inheritance and responsibility of the entire Jewish people.

There’s no rocket science in that, of course, just a rearticulation of a basic truth. The challenge–for me, anyway, and perhaps for you too–is that they can become ritualized and, in the process, lose some of what the ritual is supposed to help us do. Our moadim, our sacred times, are invitations to deeper awareness, a richer encounter with the Divine within ourselves and one another. Every week on Shabbat, and then throughout the other special moments of our holiday calendar, we can step into an opportunity for blessing, pause and rest through which we recognize the presence of the Shechina within, between, and among us. What an incredible gift, what an astonishing inheritance.

Every Friday morning, IJS President & CEO Rabbi Josh Feigelson shares a short reflection on the week in preparation for Shabbat. Josh weaves together personal experience, mindfulness practice, and teachings from the weekly Torah portion in a uniquely accessible and powerful way. Sign up to receive Josh’s weekly reflections here.

May 13, 2024 | Blog, by Rebecca Schisler, Core Faculty, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

How can we maintain our faith, emunah, in the face of struggle and strife? In this video, Rebecca Schisler shares a teaching from Exodus that can help us understand what it takes to keep faith alive even when facing profound doubt.

May 13, 2024 | Blog, by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

Written by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, from the IJS Awareness in Action Program

When we look for an example of emunah (the soul trait of trustworthiness or steadfastness) in Jewish tradition, we return to Moses, the trustworthy leader of the Israelites, during their 40 years of wandering in the wilderness.

In fact, God comments on Moses’ trustworthiness, comparing Moses to other prophets. God communicates with other prophets through dreams or visions. But according to Numbers 12, verse 7, “Not so with My servant Moses; he is trusted (ne’eman) throughout my household.”

The 11th-century French Rabbi, Shlomo ben Meir (Rashbam, the grandson of Rashi), looked at this verse and provided us with a beautiful image we might hold in mind about what it might look like for us to practice emunah, to be trustworthy, and what the results may be for the confidence we engender in our relationships. He said, “Trusted, ne’eman, in the verse, means steadfast and rooted every moment of the day. As the prophet Isaiah says (Isaiah 22:23), ‘I will affix him as a peg in a secure place – b’makom ne’eman.’ The peg stuck in strong ground will not easily fall.”

Our practice of emunah, meeting our commitments, showing up for others even when it is hard, unpleasant, or inconvenient, really being there for the people who need us, helps us be like a tent peg planted in firm ground, rooted, solid, unflagging, steadfast.

This image of a tent peg is instructive, for the peg moves with the soil even as it keeps the tent from toppling over. Far from conveying stubborn inflexibility, emunah entails being responsive to the terrain of our lives and relationships, in a way that holds us and others up. We may not be able to show up in this way every moment of the day, as Moses did. Day after day, providing the people with water and food, a new structure for their society through the Torah, a sense of safety, and an ongoing sense of God’s presence.

In our mindfulness practice, we can apply hitlamdut, non-judgmental curiosity, and grow more aware of the habits of heart and mind that hinder our ability to show up for others and for ourselves. We can notice our bechirah, our capacity and opportunity to choose a wise response informed by our innate emunah, trustworthiness. And we can allow the godly faithfulness to flow more easily through us, so that we show up more consistently, day by day.

May 9, 2024 | Blog, Rabbi Josh Feigelson, PhD, President & CEO, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

My sons never knew their maternal grandfather. I never knew him either. He died of a brain tumor while my wife Natalie was in college, which was before we met.

By all accounts Peter was a wonderful person. He loved chess and theater and active life outdoors. He loved his daughters and, no doubt, would have doted on his grandchildren. He was beloved by his extended family.

While all of that is good in and of itself, what makes it more remarkable is that my father-in-law was born in the Ukrainian forest in 1942 while his parents fought the Nazis in a brigade of Partisans. At one point, as an infant, he was hidden, found by the Germans, and left to die—only to survive miraculously when the soldiers either had compassion or didn’t want to waste a bullet on him. His father took the baby to a non-Jewish farmer and, at gunpoint, made him pledge to care for the child until after the war, which he did.

The family eventually made its way to Canada, where Peter grew up and made a life and met Natalie’s mother, whose parents found refuge in Israel following their own stories of imprisonment by the Russians during the war before eventually moving to Canada as well. Today Natalie, among other things, helps run a graduate degree program in Israel education. (Not to be outdone, her younger sister is currently the Canadian ambassador to Croatia, which during World War II was a puppet state of Nazi Germany and a collaborator in the Holocaust. Take that, Hitler.)

My own ancestors immigrated to the United States before the Shoah, and thus it was not the presence in my life growing up that it was for Natalie (and for many Canadian Jews of her generation). Israel, however, was and has remained a major part of my family’s story: my parents lived for a year in Israel with my older brothers before I was born; my eldest brother made aliyah after college and has been blessed with five children and two grandchildren; and I lived there for two years as a student, the latter of which was with Natalie when our eldest son was an infant.

This week, which began with Yom HaShoah (Holocaust Remembrance Day) and concludes with Yom HaZikaron (Israeli Memorial Day) and Yom HaAtzmaut (Israel Independence Day), is thus an important and meaningful one in my own life and that of my family, if for no other reason than that our own personal stories are so wrapped up in their larger narratives. A hair’s breadth, a single bullet, separates the existence of my wife and my three children from non-existence. For us, that miracle is on a level of the action of Pharaoh’s daughter to save the baby Moses from the Nile. One who saves one life saves, creates, sustains an entire world, entire worlds: a miracle.

I thus frequently wonder about that moment, when the Nazi soldiers stood over my father-in-law’s infant body: What was going through their minds? Was there an argument? Did some tiny modicum of compassion swim its way from their hearts to their heads to their hands? Did a still, small voice of the Divine speak into their ears and lead them to lower their weapons? I want to believe that some element of rachamim, some kind of mercy, was present in that instant—rachamim which is rechem, the womb in which life in all its manifold possibilities gestates and grows, even in a speck of an instant in the Ukrainian forest.

I do not have a political point with this message. If this story needs a point (does it?), perhaps it’s no more and no less than a call to compassion. As my wonderful French-Israeli colleague Rabba Mira Weil shared on our Daily Sit on Yom HaShoah this week (see especially her comments after the sit), compassion has been hard for many to feel in the wake of October 7 and the painful, devastating months that have followed. And it feels like so many hearts are only getting harder, the polarities growing stronger, the shouting getting louder, the space for rachamim—between Jews and other Jews, between Jews and Palestinians, between Jews and the rest of the world—shrinking and shrinking.

Parashat Kedoshim (Leviticus 19:1-20:27) that we read this week is the Torah’s clarion call to holiness, and so much of it is centered on awareness of and compassion for those who lack power and agency: not putting a stumbling block before the blind; not oppressing the stranger; leaving the gleanings of the harvest on the ground for the poor to take. These are all, in their way, expressions of rachamim, gestures of compassion that are the wellspring of holiness. In the words of a contemporary commentary on the Torah portion’s most famous line: “Love your neighbor as yourself—even when your neighbor isn’t like yourself” (which of course invites the question: who is really like or unlike any of us, and how do we make that judgment?).

This is the essence of a life of holiness, a life of Torah, and I would suggest it applies even when it’s hard—even, that is, when we need to have compassion on ourselves for not mustering as much compassion as we feel like we should. That’s where the Torah asks us to dig deeper, to try a little more, to yes treat ourselves with compassion—but also to not let ourselves off the hook from seeking to be compassionate. As Moses’s story illustrates, as my own family’s story illustrates, the entire world depends on it.

Every Friday morning, IJS President & CEO Rabbi Josh Feigelson shares a short reflection on the week in preparation for Shabbat. Josh weaves together personal experience, mindfulness practice, and teachings from the weekly Torah portion in a uniquely accessible and powerful way. Sign up to receive Josh’s weekly reflections here.

May 2, 2024 | Blog, Rabbi Josh Feigelson, PhD, President & CEO, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

In recent days I feel like I’ve been living in a world suffused with the word camp. The encampments on college campuses, which are themselves reflective of ideological and political camps, have occupied our collective attention. As the parent of one student in college and another about to graduate high school, I have been following events with concern. As a scholar of the history of Jews and universities, I have been following them with keen interest. As an American Jew, I have been following them with a not inconsiderable dose of anxiety and worry.

Yet, in what I’m choosing to believe is a not coincidental twist, the drama on so many campuses played out while my family and I were at a different kind of camp, namely the annual Passover experience at Camp Ramah in Ojai, California. For ten days, from the day before the holiday to the morning after it concluded, we ate and talked, prayed and sang, celebrated and studied with a wonderful group of nearly 200 Jews young and old in the sunny, warm, and breathtakingly beautiful setting of the mountains north of Ventura. In the spirit of Passover, I felt like I was liberating myself from email, social media, and news feeds as I reconnected with family, friends, the Jewish people, the natural world, and the Creator. It was an incredible blessing. (Picture is of my two younger sons overlooking Lake Casitas.)

Still, many of the sessions that I and other faculty members taught inevitably focused on the questions of the day: In Israel and Gaza, of course, but also the college campuses which have become so central to American Jewish life, and the more familiar terrain of our communities and our own minds and hearts. In particular, a question that seemed to pervade the whole week was some version of, How can we stay sane in this world that is enduring so much suffering? And how can we be mindful in the face of this constant firehose of information–some of which is true, much of which is false, and the totality of which is overwhelming?

Those questions offered me an opportunity to talk about the Jewish mindfulness practices I use in my own life to try to help, which include meditation, intentional consumption of media, Tikkun Middot practice when it comes to social media posting, setting app limits, and meeting sensations of judgment with curiosity rather than conviction (“Be curious, not furious,” as one participant put it). Our practices are designed for moments like these. They can help us sustain the habits of the heart we need to live and participate wisely and mindfully as members of a diverse democracy.

Because this year is a leap year on the Jewish calendar, we encounter the somewhat unusual situation in which the Torah portion for this week that immediately follows Passover is Acharei Mot, which is about Yom Kippur. We have barely put away the matzah and our attention is turned toward the opposite end of the year and our people’s other most important holiday.

The Torah describes Yom Kippur as a “Shabbat Shabbaton,” a day of complete rest (Lev. 16:31). Commenting on this verse, Rabbi Mordechai Yosef Leiner observes that the aim of the restrictions of Yom Kippur is to help us cultivate a profound sense of yishuv hada’at, a settled and clear mind, which is the essence of Shabbat. When we can do so, he writes, the flow (shefa) of the Holy One can fill us completely, without any limitation. We can be fully present–and can be vessels for the Divine Presence.

Of course, Yom Kippur represents this dynamic at its peak–a day on which we can be particularly and especially suffused with the presence of the Holy One. Yet the kind of presence and awareness–the yishuv hada’at, the settled and clear mind at its core–is available to us every week on Shabbat, and in every moment in the form of “Shabbat Mind.” It is reflected and embodied in speech and action that is full and mindful, not empty and reactive.

These qualities, of mindful presence and expansiveness, are also related to the central theme of Passover, the exodus from Egypt–the place of narrowness and constriction. Which suggests that, though these holidays are on opposite ends of our calendar, they are profoundly connected. Political freedom is not complete without spiritual freedom, and spiritual freedom is not whole without political freedom. As we continue to witness and engage in discussion, debate, and activism centered on political camps and encampments, my humble observation is that such work, wherever we stand in relation to it, will only benefit from greater yishuv hada’at–the spiritual practices of mind and heart that weave together our larger camp that exists within, between, and among us.

Every Friday morning, IJS President & CEO Rabbi Josh Feigelson shares a short reflection on the week in preparation for Shabbat. Josh weaves together personal experience, mindfulness practice, and teachings from the weekly Torah portion in a uniquely accessible and powerful way. Sign up to receive Josh’s weekly reflections here.

Apr 18, 2024 | Blog, Rabbi Josh Feigelson, PhD, President & CEO, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

“All revolutionaries are patricides, one way or another.” That’s a line from Yuri Slezkine’s classic of modern Jewish history, The Jewish Century. The book was published in 2006. A few years later, when I was working on my doctoral dissertation, that line became a powerful lens as I reflected on the intergenerational conflict in American Jewish life in the late 1960s and early 70s.

My thesis was that a significant strain in American Judaism in those days involved conflict between generations of parents, grandparents, and children as they shaped their identities and relationships with Jewish life. Some of this was bound up with general patterns of rupture and reconstruction that have repeated in many immigrant communities–not just Jews–in the United States. “Old world” customs give way to new forms of life (‘patricide’ means killing one’s father), often accompanied by pain and strain. A younger generation looks upon its elders and breaks from their “outmoded” ways; the older generation looks upon its progeny and laments what they have become.

Obviously that’s a very rough heuristic. It works well for the movies (think of The Jazz Singer–both the Al Jolson and Neil Diamond versions) and it does reflect some truths in real life. But individual families and larger histories are, of course, more complex than that. As my doctoral adviser, Robert Orsi, put it in a memorable note on a draft of one chapter: “No one speaks for a generation, not even Dylan.” In the case of American Jewish life in the 60s and 70s, that was reflected in the move to recover and re-embrace attachment to and expression of Judaism: in the Havura movement, the ba’al teshuva phenomenon, the rise of Chabad, an embrace of Zionism in the wake of the Six Day War in 1967, and a general reclamation of Jewish history and thicker Jewish identity among a younger generation that gained strength in those years.

This is already much more academic than most of my Friday reflections, and I don’t intend to rehash my doctoral work here. (If you’re really that motivated, you’re welcome to buy a copy. Here’s the link.) Usually I start these reflections with a personal story, not with a quote from an historian. So why all this today?

As I shared in my podcast this week, like many folks I’m freaking out a bit about the Seder this year. I’m worried about what feels like a moment of profound strain, even rupture–not exclusively a generational one (remember that line about Dylan), but along multiple lines that ultimately trace their way through our views on and relationships with Israel. I’m worried about how that’s going to be reflected at our Seder tables this year. There is so much pain, so much anger, so many profoundly conflicting views of morality, of what Torah asks and demands of us right now. I’m worried about our ability to stay together as a family, both in the immediate sense and, more collectively, as a Jewish people.

I have long been drawn to the last lines of the haftarah for Shabbat HaGadol, this Shabbat that comes immediately before Passover: “Lo, I will send the prophet Elijah to you before the coming of the awesome, fearful day of YHVH. He shall reconcile parents with children and children with their parents, so that, when I come, I do not strike the whole land with utter destruction” (Malachi 3:23-24). The image of parents and children turning towards each other–the word in Hebrew is heishiv, from the same root as teshuva, the returning we do during the High Holidays–has always struck a deep chord for me, as Passover is, more than anything, a time that my own heart turns towards my parents and my children.

I write about this line virtually every year. Yet quite honestly I usually dodge the challenge presented by that very last clause, the one about striking the whole land with utter destruction. Too hard, not relevant, I tell myself. In this year, however, that simply isn’t and cannot be the case. There is literal destruction in the land and, with it, enormous destruction that has occurred in our language, our relationships, our people, our families, our hearts. And it’s the fear of seeing that destruction reflected at the Seder table that is freaking me out.

And so (say it with me): This is why we practice. To acknowledge those very deep and potent fears, to let them have their space–and then to make mindful, wise, compassionate, and loving choices. That is the very freedom from Egypt–Mitzrayim, the place of constriction–that the Seder is about, the spiritual journey we undertake every day and in every moment. As the prophet says, we can and must turn toward one another. It is in that turning, that opening of our hearts that enables us to live together peacefully, that we manifest our freedom as images of the Divine. May it be so for us this year.

Every Friday morning, IJS President & CEO Rabbi Josh Feigelson shares a short reflection on the week in preparation for Shabbat. Josh weaves together personal experience, mindfulness practice, and teachings from the weekly Torah portion in a uniquely accessible and powerful way. Sign up to receive Josh’s weekly reflections here.

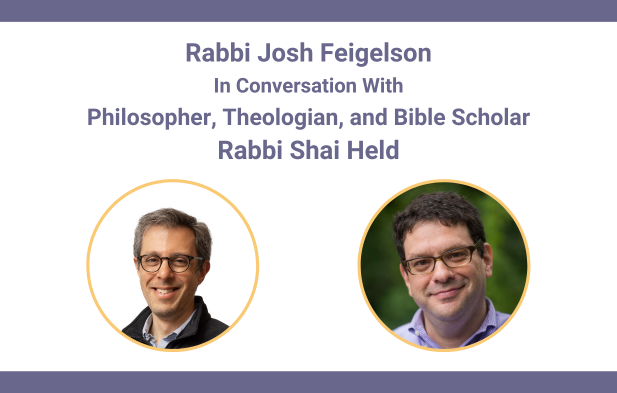

Apr 16, 2024 | Blog

We are grateful to Rabbi Shai Held for speaking with IJS President & CEO, Rabbi Josh Feigelson! Please enjoy the conversation recording below.

Rabbi Shai Held—philosopher, theologian, and Bible scholar—is President, Dean, and Chair in Jewish Thought at the Hadar Institute. He received the prestigious Covenant Award for Excellence in Jewish Education, and has been named multiple times by Newsweek as one of the fifty most influential rabbis in America and by the Jewish Daily Forward as one of the fifty most prominent Jews in the world. Rabbi Held is the author of Abraham Joshua Heschel: The Call of Transcendence (2013) and The Heart of Torah (2017). His newest book is Judaism is About Love, published by Farrar, Straus, & Giroux.

Apr 11, 2024 | Blog, Rabbi Josh Feigelson, PhD, President & CEO, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

One of my favorite parts of Shabbat is reading the New Yorker. It’s the only time during the week I can sit for an hour or two and just read, uninterrupted by demands of work or family. And as I told my eldest son recently, while college certainly helped with my own writing, it was in reading the New Yorker that I really learned how to write. So I find those Shabbat mornings when I’m sitting at the kitchen table, sipping my coffee, reading Adam Gopnik or Jill Lapore or David Remnick, to be both immensely pleasurable and, still, highly instructive.

There was an article in last week’s issue by Leslie Jamison about gaslighting, the psychological phenomenon in which one person (usually a parent or a spouse) profoundly undermines not only the reality of another, but, crucially, a person’s belief in what their own senses tell them is true. As Jamison notes, the term comes from a 1944 film, “Gaslight,” in which a husband goes up to the attic every night to search for a set of lost jewels that belongs to his wife–in an attempt to steal them. As he does so, he turns on the gas light, which causes the other gas lights in the house to flicker. When Paula, the wife, asks him about it, he convinces her she didn’t see anything. That firm denial steadily causes Paula’s entire reality to wobble: If she can’t trust her own eyes, what can she trust?

Jamison’s piece explores how the term has exploded in usage over the last decade or so. (In 2022 it was Merriam-Webster’s Word of the Year.) For many people, discovering the term is a revelation, as it enables them to recognize the ways that authority figures have manipulated, abused, or injured them. Yet Jamison also notes that the phenomenon is not necessarily such a rare thing, but might, in fact, be a more common part of all of our lives. As she talks to an expert, she realizes that every time she tells her young daughter that she is ‘just fine’ when she obviously is not, or when she blames her daughter for making them late getting out the door in the morning when, in fact, it’s her own fault for not getting them moving sooner, she might be committing her own, milder but still real, acts of gaslighting. To which the expert responds, “Yes! Within a two-block range of any elementary school, just before the bell rings, you can find countless parents gaslighting their children, off-loading their anxiety.”

One way to read Parashat Tazria (Leviticus 12-13) is as a reflection on epistemology, or how we apprehend reality. The bulk of the Torah portion is devoted to a kind of medical manual for the ancient priests, who were charged with looking at skin infections to determine what they were and what kind of treatment they required. Within chapter 13 alone, the word “see” (r-a-h in Hebrew) is present in almost every verse, nearly 40 times. The priest is charged with looking, investigating, forming a judgment, and ultimately pronouncing reality based on the color of the lesion, the presence or absence of hair, the spread, etc. And what the priest says becomes the shared truth of the patient and the community.

This is not a narrative portion of the Torah (in fact it’s about as Levitical as Leviticus gets), and we don’t hear anything about the experience of the patient, their loved ones, or the priest. But we can try to imagine what it might have been like to wake up one day and discover something off or strange in our body–on one level or another, I expect every human being has experienced that–and what happens next in our minds and hearts. “Huh, what is this? Is it something terrible, or is it benign? Should I go to the doctor right away, or maybe I can wait a week and see what happens?”

I certainly have had such moments, and I expect you have too. Within them, we can feel anxiety as not only our reality shifts, but our confidence in our apprehension of reality is also challenged: “Did I really see what I think I saw? Did I gaslight myself? Maybe I didn’t. Maybe it’s even worse? Maybe I should have known this thing was coming weeks ago. Maybe I’m a bad person!” Commence downward spiral.

This isn’t limited to bodily maladies; it applies to virtually everything in life–which I believe is part of the larger point of this Torah portion. The character of the priest here reminds me of no one so much as Adam, the image of God, in the opening chapter of Genesis (another chapter in which seeing is a motif): looking, investigating, forming judgments, giving names and labels. That process is one we do all the time; it’s foundational to how we interact with the world. And precisely because it’s so fundamental, gaslighting–and the larger destabilization of our reality that feels like a growing phenomenon in our political and media life–is particularly resonant.

In my view, Judaism properly understood is a mindfulness practice. The priest’s responsibility is, in fact, the charge and invitation to each and every one of us: to look, to investigate, and to make wise and mindful judgments. As the priest in Tazria reminds us, that process involves study and acquiring knowledge–and it involves giving ourselves the time and space to see clearly and honestly. So often today I find myself pressed to make a snap judgment. Yet through our practice we can access that other great gift of the opening chapter of Genesis, the expansiveness of Shabbat. Through that, we can create the time we need and deserve to examine reality more closely, perceive more clearly, and judge more wisely.

Every Friday morning, IJS President & CEO Rabbi Josh Feigelson shares a short reflection on the week in preparation for Shabbat. Josh weaves together personal experience, mindfulness practice, and teachings from the weekly Torah portion in a uniquely accessible and powerful way. Sign up to receive Josh’s weekly reflections here.

Apr 4, 2024 | Blog, Rabbi Josh Feigelson, PhD, President & CEO, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

Nearly twenty years ago my family and I moved to Evanston, Illinois. I had just been ordained a month earlier, our son Micah had just been born two weeks prior, and we moved into an empty condo apartment two blocks from the Northwestern University Hillel, where I had taken a job as the campus rabbi. Natalie and I had rented apartments in New York up until then, and this was the first place we owned.

I remember that the confluence of all these changes made it feel different, like we had arrived at this new, officially more grown up stage of life. That was especially true on our first Shabbat. Up until then, we had always eaten on a small Ikea table and sat on folding chairs. But here was a big new walnut dining room table and eight chairs, one we had paid good money for and that would be with us for a long time (it still is). I remember feeling overwhelmed as I sat there and took it in. For the first time, I really felt like we were truly, deeply at home.