Feb 4, 2019 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

This month begins IJS’s 20th anniversary year! I was not personally present at the very beginning in 1999 when Rachel Cowan (z”l) and Nancy Flam brought together an extraordinary group of spiritual teachers and seekers in a process of sharing and learning that became the Institute for Jewish Spirituality. So much has changed and evolved since then.

This month begins IJS’s 20th anniversary year! I was not personally present at the very beginning in 1999 when Rachel Cowan (z”l) and Nancy Flam brought together an extraordinary group of spiritual teachers and seekers in a process of sharing and learning that became the Institute for Jewish Spirituality. So much has changed and evolved since then.

But one thing that has not changed has been the core values that undergird our work. Like all values, they are aspirational. Like all intentions, we fall short occasionally and recommit ourselves to them anew. As we take stock of the last 20 years and begin the process of reflection and rededication towards the next 20, I wanted to share these powerful values with you in hopes that they inspire you as much as they inspire me.

Institute for Jewish Spirituality: Our Guiding Principles

Shiviti Adonai lenegdi tamid: I strive to cultivate an awareness of God in every moment.

We seek a spiritual practice that wakes us to God’s reality in all aspects of our lives. The whole earth is full of God’s glory!

Tzelem Elohim: The Divine Image

We affirm and strive to reflect the divine and infinite potential in each human being.

Kehilla Kedosha: Holy Community

Creating and maintaining a safe, intentional community allows for deep listening to ourselves and to others, and opens us for healing, connection and insight.

Im eyn ani li mi li?: If I am not for myself, who will be for me?

Jewish leaders best serve and inspire their communities when they cultivate and refine their own spiritual lives–you can’t give what you don’t have.

La aleycha hamlachah ligmor: You do not have to finish the work, but neither are you free to desist from it

Spiritual growth is a life-long process that requires ongoing commitment, practice and guidance.

Tikkun HaNefesh and Tikkun Olam

We understand that our work to cultivate awareness leads inexorably to acts of kindness and justice.

Ki tavo chochmah b’libeycha, v’da’at l’nafsehcha yinam: For wisdom will enter your mind and knowledge will delight you

While we inherit a unique religious tradition, we are open to, benefit from, and integrate wisdom from other traditions.

Redeeming Sparks of Language

We are committed to helping people connect their traditional Jewish God, language, and ritual with their authentic inner experience in order to nurture and expand their sense of experiencing of God as Jews.

Mechadesh b’chol yom tamid ma’aseh beresheet: The world is constantly created anew

We believe in the power of Teshuva – the capacity of Jews and Judaism to change and grow and thereby be of greater service to themselves and to the world.

Dec 3, 2018 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

Hanukkah is upon us and with it the aptness of all the metaphors of bringing light into the darkness. A less examined theme of the holiday, however, at least in many spiritual circles, is holy boldness – the decisive action that the Macabees took in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds that enabled them to defeat the wicked government that vastly outweighed them.

We tend to shy away from exploring this kind of strong action because it can seem so antithetical to the spiritual endeavor of finding inner peacefulness and because it can too easily veer into bold fanaticism, as the Hasmonians themselves exemplified. And yet, holy boldness, the courage of the spiritual warrior, is an important middah, or trait, even (and maybe especially) for the contemplative repertoire.

One teaching on how to approach this boldness comes from the daily liturgy. In the morning service, the first prayer before the Shema offers an image of angels. The prayer book describes the angels in vivid terms: “They are all loved, they are all clear, they are all bold and they all do the will of their Maker with fear and awe.”

At first, the description appears rather random. Why those three particular adjectives, other than the fact that the Hebrew words for “loved,” “clear” and “bold” follow the order of the Hebrew alphabet? But if we look carefully, using what we know from our contemplative practice, something quite beautiful emerges.

First, the angels know that they are ahuvim, loved. This is the crucial first step, to take in the awareness of being precious, seen, cherished. From that place of warmth and connection, they can be brurim, clear. Feeling loved can help clear the delusions so that we can see with greater clarity what needs to be done, as well as our motivation for acting. And then, when the path forward is clear, the angels can act as giborim, as courageous and bold heroes. But even here, they are aligning themselves with humility and a sense of serving – not of their own will, but of the great Source of life and creativity in the universe.

What marvelous instructions! A courage that is rooted in love, shone through with clarity and in humble alignment with what needs to happen. May this Hanukkah provide us with opportunities to explore this holy boldness so that we can through our actions help bring more light into this dark season.

May 2, 2018 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

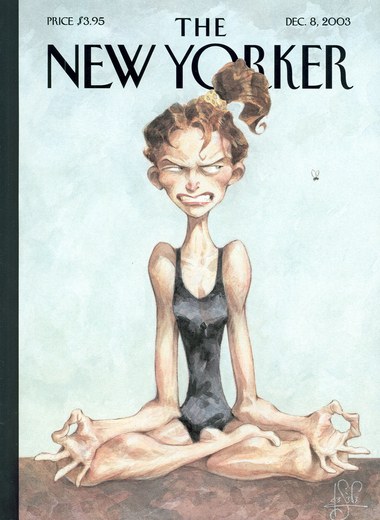

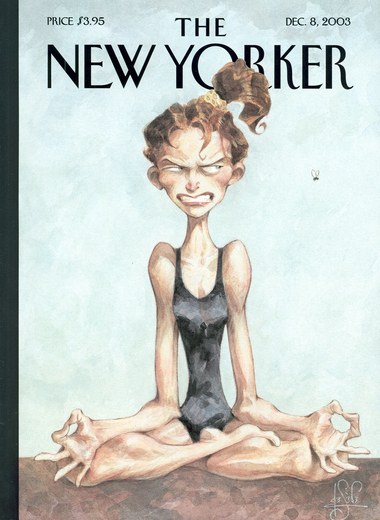

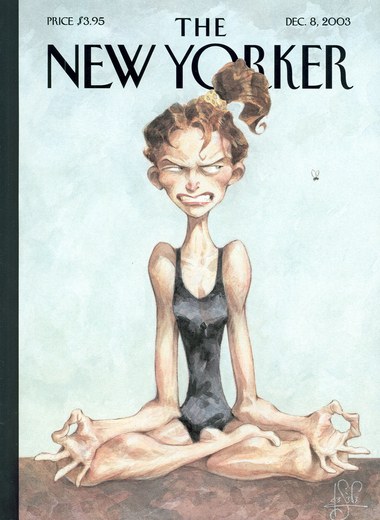

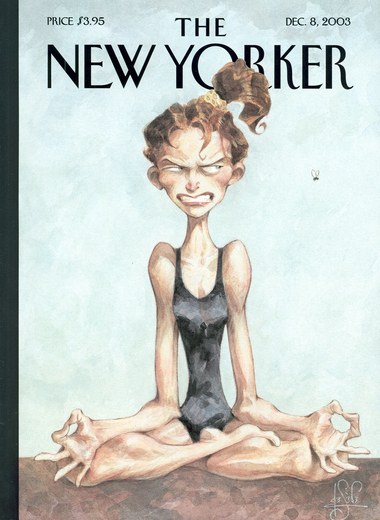

Several years ago, the New Yorker featured a cover that showed a woman sitting in the lotus position, ostensibly meditating. You can tell she is so wound up that she is about to jump out of her skin. If you look carefully in the direction of her baleful glare, there is a little fly, innocently tooling around.

Several years ago, the New Yorker featured a cover that showed a woman sitting in the lotus position, ostensibly meditating. You can tell she is so wound up that she is about to jump out of her skin. If you look carefully in the direction of her baleful glare, there is a little fly, innocently tooling around.

One of the reasons I find this image so funny is that I have been there myself so many times. I sit down to meditate or to pray with great zeal and focus – and then, something interrupts my plan. The drive I feel to engage in practice ends up eclipsing the practice itself; my focus shifts to how my plan was derailed and that I couldn’t meditate or pray as I (or my ego) wanted.

There is a seeming paradox between zeal and contemplation. Zeal is about acting now with a great sense of passion and confidence. Zeal is impatient, directed, quick. Contemplation, on the other hand, usually evokes “sitting with the issue” for a while. It is slow, receptive, internally oriented. How, then, can zerizut (zeal, alacrity) be a contemplative practice?

One answer might be one of my favorite teachings from Sholom Noach Berezovsky, also known by the title of his book, Netivot Shalom. “First comes effort,” he taught in multiple places. “Then comes a gift.”

When it comes to spiritual practice, it is important to draw upon our zeal. Zeal enhances our motivation, helps us overcome our inertia, commit to the effort. Spiritual practice is similar to going to the gym. It’s not enough to know about the benefits; you have to actually go to the gym before any transformation can take place. Zeal helps us make the effort and return to it again and again.

And then comes a gift. It’s not “the” gift; it’s “a” gift. We don’t actually know what will happen when we engage in practice. Sometimes we get distracted and annoyed. Sometimes it seems like nothing happens at all. And occasionally something very sweet and still and connecting opens within us. But whatever happens, whatever the experience is, is a gift.

So first the effort, and then a gift. When we stay focused on the effort, we can get so stressed by a small “failure” that we can forget why we are engaging in practice. But if we can lighten our grasp on the expectation created by our zeal and look up and see what is true in this moment, we can find our experience – whatever it is – to be rich and filled with grace. Or as the Irish poet, Galway Kinnell wrote:

Whatever happens. Whatever

what is is is what

I want. Only that. But that.

Feb 13, 2013 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

It is interesting that it took a snowstorm to turn New York City into Jerusalem on a Friday evening.

Like many people who have spent time in Jerusalem, one of things I love the most is the way Friday afternoons come into the Jewish parts of the city. Bit by bit, the stores close and the roads empty out. The sounds of the usual bustle begin to subside and a calm begins to pervade the squares and streets. By the time the sun sets over the plain below, it can feel like the whole city has taken a deep breath and let it out slowly.

Last Friday, with the approach of Snowstorm Nemo, New York City could have been Jerusalem. Sleet was falling in the afternoon and people began leaving, getting to where they would stay for the duration of the storm. Even in Midtown, where our office is, bit by bit, there were fewer cars, less honking and sirens. We closed the office a little early. And by the time the snow began to fall in earnest, later in the evening, as I was on my way to Shabbat dinner, there was a magical hush everywhere. The streets were mostly empty except for people walking, some with their dogs. The glow from the strings of left-over holiday lights caught the softly falling snow. The usually frantic city felt soothed and quiet.

One of the things I love about New York City is the wonderful energy and astonishing abundance of people and buildings and things to do and see and eat and explore. There is usually no stopping it or even any desire to stop it. But on this Erev Shabbat, it seemed like the city shavat vayinafash – stopped and took a breath.

By Shabbat morning the sun was shining and the sky was blue. I made my way to Central Park to explore the snowy woods and to watch the kids (of all ages!) playing in the snow. New York was returning to itself: noisy, colorful, vibrant. Yet, the magic of the snow stayed all through Shabbat. It wasn’t until Sunday that there was more gray slush than pristine fields of snow – just in time for a new workaday beginning to the week.

Jul 25, 2012 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

The July retreat season flew quickly by. For me, the hidden jewel of the season was the silent contemplative Shabbat. It combined two things that I treasure as part of my spiritual life: Shabbat and silence.

Shabbat and silence can be surprisingly similar. To the uninitiated, Shabbat can seem like a bunch of rules, mostly involving things you can’t do. But those who regularly observe Shabbat know that the structure of the tradition allows for something magical to happen. By temporarily turning away from the demands of work, entertainment and acquisition, we can make space for experiences of true meaning.

Silence works in a similar way. By temporarily not engaging in social conversation, I make space to find deeper meaning in my own life. My habitual thoughts can rest a little. I give myself time to notice how I am really doing, not just how I want to be doing. What is going on in my heart underneath all the distractions of life? What wisdom can emerge from that knowledge? How does the Divine move through it all?

Some of that I can also do in conversation with someone I trust. But in silence, I don’t have to explain or justify anything to anyone. No one will demand an answer or offer a solution. If I am feeling sad, I can feel sad. If I am feeling alive and grateful, that’s fine. I don’t have to define it or describe it or analyze it. I can just feel it and be it – until it shifts and becomes something else. There is a comfort and a safety in the silence. I can lean into it, knowing it will support me and lead me where I need to go.

It may seem counterintuitive that being quiet with a group of other people who are also in silence is much more powerful than silence alone. And yet, that is true. (At least, that is true for me.) I often feel a strange intimacy and affection for fellow meditators, even when I don’t know any biographical information about them. The silence allows me to remember the fundamentals of being a human being: the longing for love and meaning, the pain of suffering, the inevitable passing of time. The realization that I share those things with every other person becomes a lived experience in silence, not just a beautiful thing to think about.

A silent Shabbat – most coveted of days!

This month begins IJS’s 20th anniversary year! I was not personally present at the very beginning in 1999 when Rachel Cowan (z”l) and Nancy Flam brought together an extraordinary group of spiritual teachers and seekers in a process of sharing and learning that became the Institute for Jewish Spirituality. So much has changed and evolved since then.

This month begins IJS’s 20th anniversary year! I was not personally present at the very beginning in 1999 when Rachel Cowan (z”l) and Nancy Flam brought together an extraordinary group of spiritual teachers and seekers in a process of sharing and learning that became the Institute for Jewish Spirituality. So much has changed and evolved since then.