Aug 1, 2019 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

The phrase “community of practice” is one of those bandied-about terms that seems particularly suited to Jewish spiritual groups: Community and practice – how obvious and how obviously beneficial!

And yet, it’s also not so simple. Just because you happen to share a profession, a craft or a practice with a group of other people doesn’t mean that the group will in fact be supportive or a good learning environment. The stories to the contrary are many and we might even say that particularly in our individualistically oriented society, the difficulties of communities of practice sometimes seem to outweigh the benefits.

One way to address this is to think of creating communities of practice as a spiritual practice itself. We can start by setting explicit intentions. By setting an intention, we have an anchor that we can return to – again and again – when we notice that we have moved away from the intention.

Those of you who have participated in IJS retreats know that we begin each retreat with guidelines about creating intentions around safety. They include things like being aware of judgment arising and trying to hold it with curiosity instead of conviction; assuming and extending welcome; allowing people to listen to their own inner voice, even when we think we know what it should say; “double confidentiality” which gives people the space to say something vulnerable and not have to revisit it unless they so choose. These guidelines help create intentions for a community of practice that supports the participants in the community in doing their own deep work of truth telling and loving kindness.

In your communities of spiritual practice, what are your intentions? What kind of community are you intending to create? What kind of transformation are you hoping to cultivate? What are the conditions that will help facilitate that? How do you communicate them to the entire community?

It sounds easy – and it’s not, even in the relatively small and temporary context of a retreat. But, as those of you who have participated in IJS retreats also know, the effort is worth it. As our summer retreat season closed, we saw once again the true power of a community of seekers, coming together and finding a safe environment, the way the heart can open, bonds can form and deepen, awareness expand. And those experiences can give us inspiration and fortitude to take with us as we continue on our way.

Feb 4, 2019 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

This month begins IJS’s 20th anniversary year! I was not personally present at the very beginning in 1999 when Rachel Cowan (z”l) and Nancy Flam brought together an extraordinary group of spiritual teachers and seekers in a process of sharing and learning that became the Institute for Jewish Spirituality. So much has changed and evolved since then.

This month begins IJS’s 20th anniversary year! I was not personally present at the very beginning in 1999 when Rachel Cowan (z”l) and Nancy Flam brought together an extraordinary group of spiritual teachers and seekers in a process of sharing and learning that became the Institute for Jewish Spirituality. So much has changed and evolved since then.

But one thing that has not changed has been the core values that undergird our work. Like all values, they are aspirational. Like all intentions, we fall short occasionally and recommit ourselves to them anew. As we take stock of the last 20 years and begin the process of reflection and rededication towards the next 20, I wanted to share these powerful values with you in hopes that they inspire you as much as they inspire me.

Institute for Jewish Spirituality: Our Guiding Principles

Shiviti Adonai lenegdi tamid: I strive to cultivate an awareness of God in every moment.

We seek a spiritual practice that wakes us to God’s reality in all aspects of our lives. The whole earth is full of God’s glory!

Tzelem Elohim: The Divine Image

We affirm and strive to reflect the divine and infinite potential in each human being.

Kehilla Kedosha: Holy Community

Creating and maintaining a safe, intentional community allows for deep listening to ourselves and to others, and opens us for healing, connection and insight.

Im eyn ani li mi li?: If I am not for myself, who will be for me?

Jewish leaders best serve and inspire their communities when they cultivate and refine their own spiritual lives–you can’t give what you don’t have.

La aleycha hamlachah ligmor: You do not have to finish the work, but neither are you free to desist from it

Spiritual growth is a life-long process that requires ongoing commitment, practice and guidance.

Tikkun HaNefesh and Tikkun Olam

We understand that our work to cultivate awareness leads inexorably to acts of kindness and justice.

Ki tavo chochmah b’libeycha, v’da’at l’nafsehcha yinam: For wisdom will enter your mind and knowledge will delight you

While we inherit a unique religious tradition, we are open to, benefit from, and integrate wisdom from other traditions.

Redeeming Sparks of Language

We are committed to helping people connect their traditional Jewish God, language, and ritual with their authentic inner experience in order to nurture and expand their sense of experiencing of God as Jews.

Mechadesh b’chol yom tamid ma’aseh beresheet: The world is constantly created anew

We believe in the power of Teshuva – the capacity of Jews and Judaism to change and grow and thereby be of greater service to themselves and to the world.

May 2, 2018 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

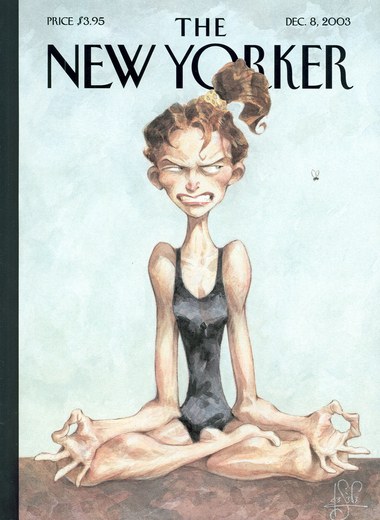

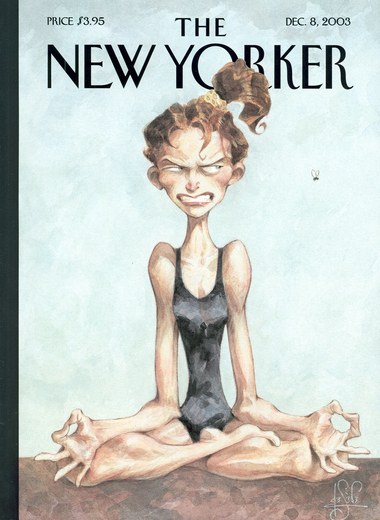

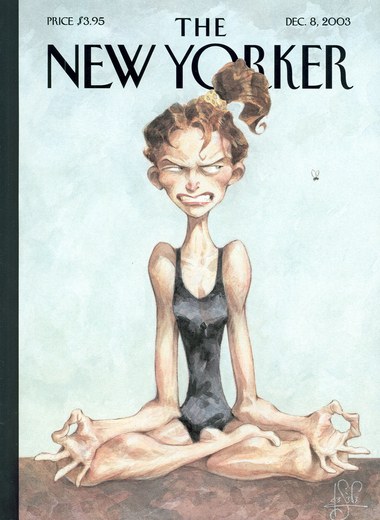

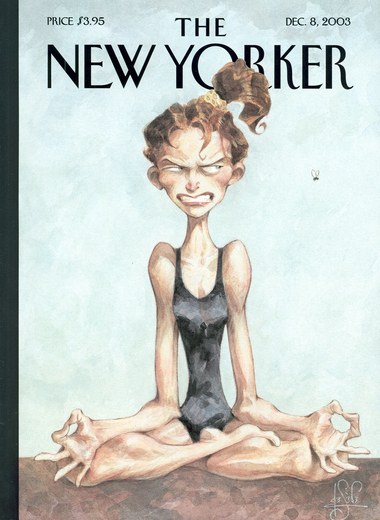

Several years ago, the New Yorker featured a cover that showed a woman sitting in the lotus position, ostensibly meditating. You can tell she is so wound up that she is about to jump out of her skin. If you look carefully in the direction of her baleful glare, there is a little fly, innocently tooling around.

Several years ago, the New Yorker featured a cover that showed a woman sitting in the lotus position, ostensibly meditating. You can tell she is so wound up that she is about to jump out of her skin. If you look carefully in the direction of her baleful glare, there is a little fly, innocently tooling around.

One of the reasons I find this image so funny is that I have been there myself so many times. I sit down to meditate or to pray with great zeal and focus – and then, something interrupts my plan. The drive I feel to engage in practice ends up eclipsing the practice itself; my focus shifts to how my plan was derailed and that I couldn’t meditate or pray as I (or my ego) wanted.

There is a seeming paradox between zeal and contemplation. Zeal is about acting now with a great sense of passion and confidence. Zeal is impatient, directed, quick. Contemplation, on the other hand, usually evokes “sitting with the issue” for a while. It is slow, receptive, internally oriented. How, then, can zerizut (zeal, alacrity) be a contemplative practice?

One answer might be one of my favorite teachings from Sholom Noach Berezovsky, also known by the title of his book, Netivot Shalom. “First comes effort,” he taught in multiple places. “Then comes a gift.”

When it comes to spiritual practice, it is important to draw upon our zeal. Zeal enhances our motivation, helps us overcome our inertia, commit to the effort. Spiritual practice is similar to going to the gym. It’s not enough to know about the benefits; you have to actually go to the gym before any transformation can take place. Zeal helps us make the effort and return to it again and again.

And then comes a gift. It’s not “the” gift; it’s “a” gift. We don’t actually know what will happen when we engage in practice. Sometimes we get distracted and annoyed. Sometimes it seems like nothing happens at all. And occasionally something very sweet and still and connecting opens within us. But whatever happens, whatever the experience is, is a gift.

So first the effort, and then a gift. When we stay focused on the effort, we can get so stressed by a small “failure” that we can forget why we are engaging in practice. But if we can lighten our grasp on the expectation created by our zeal and look up and see what is true in this moment, we can find our experience – whatever it is – to be rich and filled with grace. Or as the Irish poet, Galway Kinnell wrote:

Whatever happens. Whatever

what is is is what

I want. Only that. But that.

This month begins IJS’s 20th anniversary year! I was not personally present at the very beginning in 1999 when Rachel Cowan (z”l) and Nancy Flam brought together an extraordinary group of spiritual teachers and seekers in a process of sharing and learning that became the Institute for Jewish Spirituality. So much has changed and evolved since then.

This month begins IJS’s 20th anniversary year! I was not personally present at the very beginning in 1999 when Rachel Cowan (z”l) and Nancy Flam brought together an extraordinary group of spiritual teachers and seekers in a process of sharing and learning that became the Institute for Jewish Spirituality. So much has changed and evolved since then.