Mar 2, 2015 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

It is true that I recently got engaged, but it is also true that I had been contemplating love for some time before I met my beloved. In fact, one of the great benefits of having been single for such a long time was the experience of many kinds of love from all kinds of expected and unexpected sources: from family and friends, students and teachers. And also from sunshine and boulders and from characters in books. From relatives long dead. From God.

At a recent retreat, we had the privilege of learning with Dr. Melila Hellner-Eshed, who introduced us to the Idra Rabba, highly esoteric passages from the Zohar. According to these mystical teachings, the most ancient, primordial manifestation of God continuously trickles forth love as light or milk, without any will or effort. There are other manifestations of God that are more concerned with justice and morality, but the most fundamental nature of existence is this image of love. (Of course, the Zohar circles back to say that even though it may seem that there is a “most” fundamental aspect, everything is really a unified whole – but that’s another topic.)

Somehow it makes sense to me that if you strip everything else away, what is left is love. It is often what I experience when I reach a deep place in my practice, whether it be in meditation or in prayer. Sometimes I can sense that loving connection that is independent of will or effort. It simply is.

And this calls to mind another distinction which has been part of my musings about love: the difference between yearning and desire. Yearning is a spiritual stance, an orientation of longing to connect with that fundamental love. It is not about obtaining anything or getting any answer. In fact, yearning is its own answer.

Desire, on the other hand, is focused on an object, human or otherwise, which we may or may not acquire. It is easy to confuse with yearning, but in desire, we seek to be satisfied. And alas, as the Buddhists and others point out, desire is usually satisfied only temporarily, if at all. We often get bored with what we possess – and we experience great suffering when we do not get what we desire.

Desire arises and we can be skillful or unskillful in how we respond to it, but yearning can be cultivated as a devotional practice to help remind us of all the expected and unexpected places we might experience love. Not the love that demands conditions and reactions, but just the sweet generous love that flows in everything and which we can offer back as a gift in service of the Divine.

Oct 15, 2014 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality, Email Newsletter Full Article

For the third time in a row, I got to spend Yom Kippur and the first part of Sukkot in Israel. For Yom Kippur, I went to one of my favorite synagogues in Jerusalem where the liturgy is traditional and the singing is joyful and powerful. For me Yom Kippur is such a day of supplication. It felt particularly fitting this year to spend it praying and singing and weeping in Jerusalem.

This year I noticed a feature of the liturgy that I hadn’t paid much attention to before. Towards the end of the Kol Nidre service, the traditional prayer book goes through a recitation of the Thirteen Attributes of God four times. These thirteen attributes remind us that God is merciful and gracious, patient, compassionate and forgiving. And then at the end of the day, in the middle of Neilah, after all the prayers and poems and recitation of sins, we return to the Thirteen Attributes, not four times, but a whopping seven times.

Now, it makes sense to me that we would begin the process of Yom Kippur with an emphasis on Divine compassion and mercy. This makes it safe for us to enter into this difficult day of truth telling, remorse and pleading. We trust that our words will be heard with love. But why do we conclude the day the same way?

It occurred to me that although we spend (or at least can spend) much of the day looking into the spiritual mirror, Yom Kippur itself is not always a day of actual inner change. In fact, I would say that it rarely is such a day. When darkness falls and we get up to resume our regular lives, we may have gained greater insight into our habits of heart and mind, but without ongoing practice, it is difficult to translate that insight into real sustainable change.

Perhaps that is why one tradition is that we are not truly, truly sealed into the Book of Life until Hoshanah Rabbah, the seventh day of Sukkot. We may conclude Yom Kippur feeling exhilarated, cleansed, redeemed, but there is more work to do. So we need those extra reminders of God’s merciful attributes. In fact, we need a full cycle of seven repetitions of them to encourage us to make the difficult on-going commitment to the spiritual practices that will help integrate our new intentions into our lived lives.

As we come to the conclusion of our yearly cycle and begin the new one, may we feel upheld by compassion, patience and grace so that we can take up the transformational work of a new year. Chag sameach!

Sep 23, 2014 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality, Email Newsletter Full Article

In some ways, it is a pity that Rosh Hashanah doesn’t fall on Shabbat this year. We are going to have to listen to the shofar.

Of course, listening to the shofar blasts is one of those visceral experiences that tell us, yes, the High Holy Days have arrived. It is like hearing Avinu Malkeinu with that familiar melody or tasting apples in honey: those quintessential Rosh Hashanah experiences in the body that simultaneously ground us in this moment and bind us to other Jews in other places and times.

Traditionally, observant Jews don’t sound the shofar (or recite Avinu Malkeinu) on Shabbat. This year, Rosh Hashanah falls on Thursday and Friday. But in some ways, this is the year for the shofar to fall still so that we can listen more deeply, with greater focus.

For many of us, this was a difficult summer. Menachem Nachum of Chernobyl, the Me’or Eynayim, noted that suffering often has the result of narrowing our awareness, so that we become more focused on our suffering. It can become quite a nasty cycle.

Listening, really listening, is one of the things that can help take us out of that cycle. Listening takes us out of ourselves and into connection with others. But sometimes it can be confusing. We may listen for what is new or unknown. Or we may “listen” for a particular agenda, to the stories that reinforce what we think we already know. Unfortunately, that often leads us back to the cycle of suffering.

The shofar will be sounded this year in all the places Jews gather; listening to it has the potential to take us out of ourselves and into connection with others. But often we think we know what we will hear. What if instead, we listened as if we had never heard the shofar before? What if we listened for the echo of the shofar in our own hearts? What if we followed a recent teaching by Norman Fischer and listened to the silence from which the blasts emerge and to which they return? How might that inspire us, comfort us, sustain us in this upcoming year?

May the practice of listening – to the shofar, to the suffering of others, to our own hearts – help us bring an abundance of blessings to our world in the New Year! Shanah tovah!

PS: Speaking of abundance, check out our Shmita blog! And if you are interested in learning more about the Me’or Eynayim, sign up for our text study!

Jul 15, 2014 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality, Email Newsletter Full Article

The other day I had coffee with a friend after work. We both were in a state of anguish about the violence in Israel and Palestine. She confessed that she was feeling despair; how could things ever get better? What could possibly be the catalyst for real change?

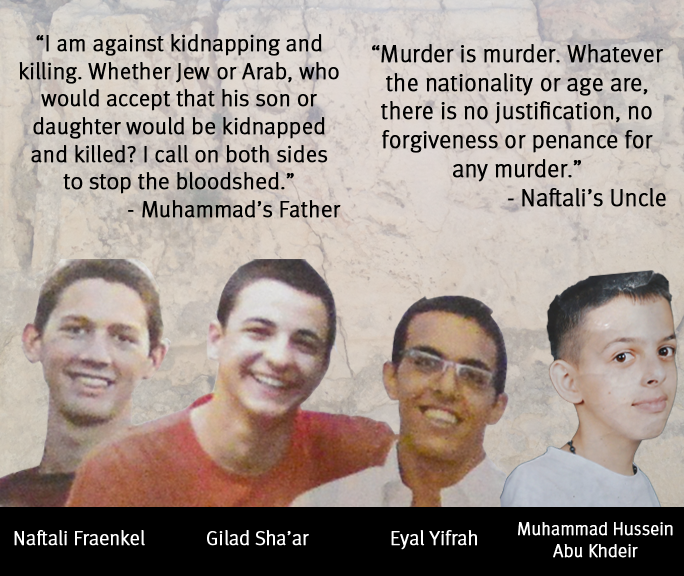

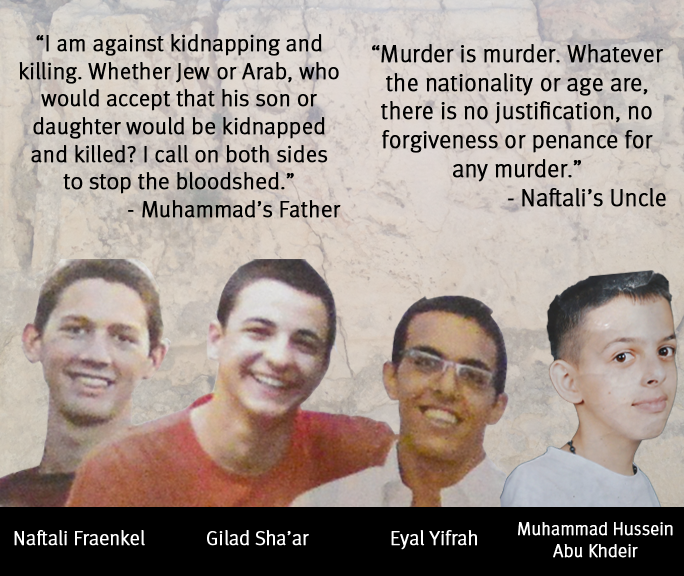

I thought about all the postings I see on social media. Ever since we learned of the murder of Naftali, Gilad and Eyal, and then the murder of Muhammed, and then the rockets and bombings, so much of the rhetoric has been justifying one side or the other or expressions of hopelessness. I feel the impact it has on my heart: I feel defended, closed, self-righteous. I experience how anger leads to more anger, despair to more despair. I feel my heart hardening into accepting the status quo cycles of violence and hatred as inevitable.

But it could be different.

How? I am so far away and so small. I am not naïve enough to think I can have any impact on Hamas or Netanyahu or anyone else who has power and weapons. And I am also not naïve enough to think that I am completely powerless.

If I want more hope, I have to add hope back into the system. If I want more openness to peace, I have to work on examples of openness to peace. If I want a vision of what could be possible in the turbulent land that I love with a full heart, then I have to speak out and encourage others to do the same.

A small example: Zena Schulman, our Communications and Development Associate, created an image last week of the four murdered boys along with quotes from their family members denouncing murder of any kind. Zena posted it on our Facebook page, where it was quickly picked up by a Jewish newspaper. A few days later I saw the image pop up on a friend’s timeline. She had seen it on the site of a reporter from Al Jazeera who had seen it from a retweeted source. Thousands and thousands of people from very different political perspectives shared that image. Zena’s picture had struck a chord of shared humanity.

Again, I don’t believe that these small tokens will stop the violence on the other side of the world. The only place I have (even a little) control is over my own heart and my own mind. But things are fundamentally interconnected. I see that beginning with my own body. When one part of my body is injured, other parts shift to compensate for it. Small things in one place create reactions in other places. And we can’t always predict how things will unfold.

We can indeed sit with anger, hatred and despair. And we can take political action in ways that make sense to us. But there is also something subversive about contributing to the discourse in a way that fosters the kind of openness that each side deplores the other side for lacking. Things do not have to be this way. I believe this with perfect faith.

If you agree, please add your voice. Let others know of your hope, your openness, your vision. Share examples of people you know who are living in Israel and Palestine and who inspire you in thinking things can be different, better. And God willing, may it soon be so.

May 12, 2014 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality, Email Newsletter Full Article

When I was a little girl, my mother taught my brothers and me to make chains of colored construction paper, one loop for each day before a longed-for event. Each evening before going to bed, we would ceremonially tear one loop off the chain and know how many days were left. In the spring we counted down to summer vacation; in the fall I counted down to my birthday.

As a people, we are similarly counting down at this time of year. During sefirat ha’omer (the counting of the Omer), each evening for the 49 days following Passover, we ceremonially mark off one more day as we proceed towards the longed-for holiday of Shavuot, the celebration of receiving Torah at Mt Sinai.

When I was a child, the purpose of the counting was to hurry along time as much as possible. It was an answer to the impatient question, “How many days NOW?” But spiritual practice helps us see this process in a very different light. Rabbi Nachman of Breslov taught that we must continually strive to see hasechel sheyesh bechol davar, the intelligence, or even signs of Divinity, that can be found in every single thing. His devoted disciple, Natan Sternharz, also known as Reb Noson, connected this teaching to counting the Omer.

Reb Noson noted that signs of Divinity can be found not just in every item, but in time as well—every day, hour and minute in its own unique way. To an ordinary person dealing with transactions and traffic and responsibilities, it’s a tall order to achieve the constancy of awareness that would permit us to see those unique signs of Divinity every day, let alone every minute! So we have this time of counting to help us practice being more finely attuned to the unique holiness of each particular day. For those of you interested in Mussar, it is very similar to the Mussar world’s offering of kabbalot, small tasks or opportunities to practice a particular middah or characteristic. The counting of the Omer is a bounded, but intensive training period for awareness.

So the counting is not to hurry along time. The counting is there to slow us down, to notice. Today is the 28th day of the Omer. What is unique about it? Where will the holiness be? Where might I find signs of Divinity if I only knew?

Wishing everyone a counting filled with wonder and blessings and joy!

Mar 27, 2014 | by Rabbi Lisa Goldstein, Former Executive Director, Institute for Jewish Spirituality

Last month I was called for jury duty and I was surprised how much the experience of sitting for three days in the jury room was similar to being on a silent retreat. Don’t get me wrong: It was not because the jury room was a still container that facilitated deep truth telling and inner exploration. Rather, in the enforced quiet of the jury room, I had a fresh opportunity to notice the judgmental nature of my own mind.

It was pretty extraordinary. I had very strong opinions about my fellow jurors; I could tell you whom I liked, whom I disliked and who intrigued me. I was undeterred by the fact that I had nothing to base any of these judgments on; I hadn’t even spoken to anyone! It was just like many of the retreats I have attended, where I invented whole stories about people based on the sound of their breathing, the pace of their walking and where they sat.

I was grateful for the past retreat experience because I was able to recognize the absurdity of my judgmental thoughts and to lightly remind myself that they were not in fact based on truth. I had a choice: I could entrench around my criticism (which was easy to do in that particular jury room, a breeding ground of entrenchment and judgment) or I could gently renew a commitment to stay open, to be curious and surprisable, and to question my own assumptions.

People often talk about spiritual practice within the narrow context of the actual practice on the cushion or yoga mat or with the prayer book or other sacred text. But to me the fruit of the practice is revealed in other contexts, often where I least expect it. The practice prepares me to notice more quickly: Oh, here is my judgmental mind. Oh, I am on autopilot again. Oh, this situation is triggering a strong reaction. What is in fact the wisest response?

And for the record, sometimes the wisest response is one of strong judgment. I left jury duty with a lot of criticism, not about my fellow jurors, but about the justice system and how it was facilitated in this particular court. Instead of sitting and sniping at strangers in my head, I managed to recognize the larger issue and subsequently channeled my discontent by writing to the judge who oversaw the jury room. I received a sympathetic response – so who knows what will emerge?

The practice manifests in mysterious ways! It is one of the great pleasures of engaging in it.