Three-Day Yontif: Bereshit 5785

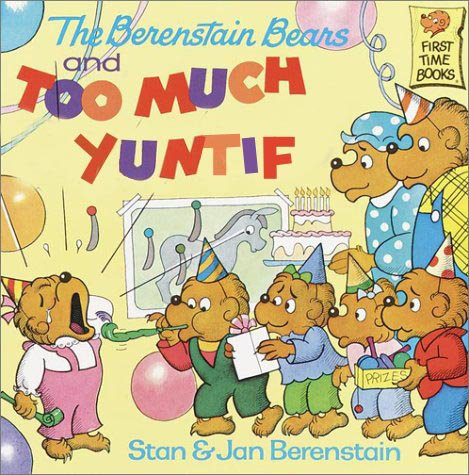

In the part of the Jewish world I live in, we are approaching the third and final cycle of what are lovingly (well, maybe not entirely lovingly) referred to as “Three-Day Yontifs.”

An explanation: Since ancient times, Jewish communities outside the land of Israel have observed not one, but two days of yom tov–holidays on which work is prohibited–at the beginning and end of Passover, on Shavuot, during the beginning of Sukkot, and on Shemini Atzeret.

Why? Because the dates of the holidays are set according to the New Moon, and according to the understanding of the Rabbis of the Talmud, the New Moon had to be proclaimed by Sanhedrin (the Rabbinic High Court) after they received testimony from witnesses who had seen it. Once they had proclaimed the New Moon, the date of the month could be fixed, and messengers would be sent out to let everyone know, e.g. “Last Tuesday was the New Moon!”

But it could take some time for those messengers to reach their destinations, and in the meantime the Jews in Huppetzville might be wondering, “According to our calculations, the New Moon should have been on Tuesday–but it also could have been early Wednesday. So is Sukkot/Shavuot/Sukkot on Tuesday, or Wednesday?” Thus, it would seem, the custom arose of keeping two days of yom tov–to cover their bases. And even though at this point we have lived with a fixed calendar for longer than the Rabbis were in the proclamation business; and even though today such proclamations would be transmitted instantaneously via livestream and text messaging, many communities including my own still keep two days of yom tov.

(One last note: Rosh Hashanah is the one holiday that occurs on the New Moon itself, which means this uncertainty applies equally inside or outside the Land of Israel. Thus the custom arose to observe two days of Rosh Hashanah worldwide. And Yom Kippur, for reasons that should be obvious, is only one day all over the world–because who could fast for 50 hours?!)

All of this means that, in a year when the holidays start on Wednesday night, those of us who celebrate two days of yom tov (=yontif in Yiddish, which is a lot more fun to say) have Thursday and Friday–and then a Shabbat immediately afterwards: i.e. a “Three-Day Yontif.” And if that happens in the fall, it happens three times. For people like me, it means that fully ten out of the 30 days of the month of Tishrei this year are Shabbat or Yom Tov. That’s a lot of time with family, a lot of time in shul, a lot of time not at work and off screens and away from the news–and also a lot of meal planning, shopping, cooking, eating, and dishwashing.

Yet I find it can also generate an effect that’s something like a retreat, or a series of retreats. Three days of immersion–times three (plus Yom Kippur, which is its own immersive experience–the Talmud compares it to a mikveh). While as a younger person I kind of resented these three-day yontifs, as I’ve gotten older I’ve come to embrace them as a gift–an extended series of retreats that supports making the month of Tishrei a month of renewal.

One of the challenges of the three-day yontif phenomenon, though, is experiencing Shabbat as different. It isn’t a three-day Shabbos. Why? Perhaps the biggest distinction between Shabbat and Yom Tov is that on Yom Tov the halakha allows us to prepare food and cook it. While there’s plenty of preparation required, it’s not like Shabbat, on which everything has to be ready beforehand. So Yom Tov isn’t quite full rest. Shabbat is still unique.

That leads to a poetic aspect of this intensive Tishrei experience. After all this activity and this extended series of spiritual retreats, we arrive back at the beginning of the Torah–at the elemental materials of creation: making, forming, shaping, dividing, beholding, naming. And I experience that as an invitation to bring this awareness of Shabbat into everything we do: to be mindful of our words, which bear the power of creation and destruction; to be conscious of our actions, through which we can increase or reduce life, love, and compassion in the world; to be aware of our hearts, which can be a home for the divine presence if we simply attune them properly.

This year, we conclude the chagim and begin a new cycle of reading the Torah amidst war, violence, and profound worry. We need this last retreat as much as ever. So: Whether or not you observe a three-day yontif, I hope you can find an opportunity during this final holiday of the season and the Shabbat Bereshit that follows it to drink from the cups of yom tov and Shabbat, and to re-enter the world renewed from this long Tishrei retreat.