A couple of friends sent me David Brooks’s column in the New York Times last Friday. While the headline made it seem that the column was about “Trump’s enduring appeal,” the column itself might more accurately be summarized as a reflection on, as Brooks put it, “the deeper roots of our current dysfunction.” As one of my friends said, they thought I might resonate with Brooks’s analysis, and especially his conclusion, that the “work of cultural repair will be done by religious progressives, by a new generation of leaders who will build a modern social gospel around love of neighbor and hospitality for the marginalized.”

They were right. I do like a lot about Brooks’s analysis, and I do resonate with his conclusion. I think that in many ways the work we do here at IJS is about laying the spiritual foundations, in both thought and practice, for “a Judaism we can believe in” (with apologies to Barack Obama), one that helps us to hold and navigate the tensions of self and other, neighbor and stranger, such that, as Parker Palmer puts it, our hearts break open rather than apart.

Last week I wrote about some of the anxieties I have been experiencing this summer in the current political climate, and about how I’ve been trying to both be aware of their roots within me and respond to them mindfully. The response to that reflection was unusually voluminous. It seemed to have struck a chord. And that was before the former president escaped assassination by a hair’s breadth. The anxiety has only increased.

What I find myself coming back to, what I think Brooks helpfully named, is that the challenge and the crisis is not something that will be solved quickly. It is generational. It is structural. Regardless of who the President is on January 20, the deeper challenges will remain. Brooks identifies two: 1) developing and agreeing on systems of government to provide meaningful representation in a postmodern era of technology and communication; and 2) filling the “void of meaning… a shared sense of right and wrong, a sense of purpose,” as he puts it. He leaves out some other biggies: Developing approaches to economic livelihood that do not depend on extracting and depleting natural resources; adapting to a less-hospitable climate; coming to some shared understanding about race and whether and how we want to continue to redress America’s original sin of slavery; continuing big questions about gender and sexuality; there are more.

These are not short-term projects, of course, and Brooks, it should go without saying, is not the first to talk about them. In the short-term, it seems a good bet that we will experience more collective turbulence, more emphasis on identity politics on both right and left, and more verbal and physical violence–especially at those who are perceived by a large group as “other” and therefore seem to impede calls for “unity.” (Jews know from this.) These tensions will continue to animate American political life, and American Jewish life too.

One of the reasons I believe our Torah at IJS is so potentially helpful for this moment is that it draws much of its inspiration from Hasidism. As I like to point out–and it still blows my own mind–Hasidism is an Enlightenment-era project. The Ba’al Shem Tov (1698-1760) and Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) were contemporaries. Yes, Hasidism happened in Eastern Europe, and thus wasn’t directly in the conversation about democracy happening in the West. But Hasidism responds to some similar questions as Enlightenment thinkers. The Enlightenment asked: How do we understand and organize our political lives when sovereignty is not exclusively concentrated in a king or emperor, but is instead shared among all citizens? Hasidism asked: How do we understand and organize our religious and spiritual lives when divinity is not exclusively concentrated in a Maimonidean unknowable unmoved mover, but is instead shared among all images of God and all of Creation?

Those questions led the Hasidic masters to articulate a theology that emphasizes the inherent dignity, uniqueness, and interconnection between all created beings. And they led Hasidism to develop both ecstatic and contemplative forms of spiritual practice, so that these ideas weren’t only intellectual assertions but actual ways of being in the world. (Unlike some Protestant traditions, however, they did not lead to democratic forms of deliberation and decision-making.) Our founders here at IJS were, thankfully, wise enough to recognize how much good such an approach can do in the world today.

This coming Tuesday on the Jewish calendar marks the Seventeenth of Tammuz, the beginning of the three week period leading to Tisha b’Av, known as bein hameitzarim, or the time of constriction. Over that span we become increasingly pulled into the orbit of despair that characterizes the saddest day of the year, the day when the Temple was destroyed and the Divine went into exile along with the Jewish people. Yet Jewish history is nothing if not the story, told again and again, of resilience and renewal in the face of hardship. As we enter into that orbit this year, I find myself breathing deeply–not only in an effort to stay calm and open, but also to tap into the deep spiritual roots of our people and our tradition. It is the sorcerer Balaam who, in this week’s Torah portion, reminds us that we have everything we need: “How good are your tents, O Jacob, your divine dwelling places, O Israel.” (Num. 24:5)

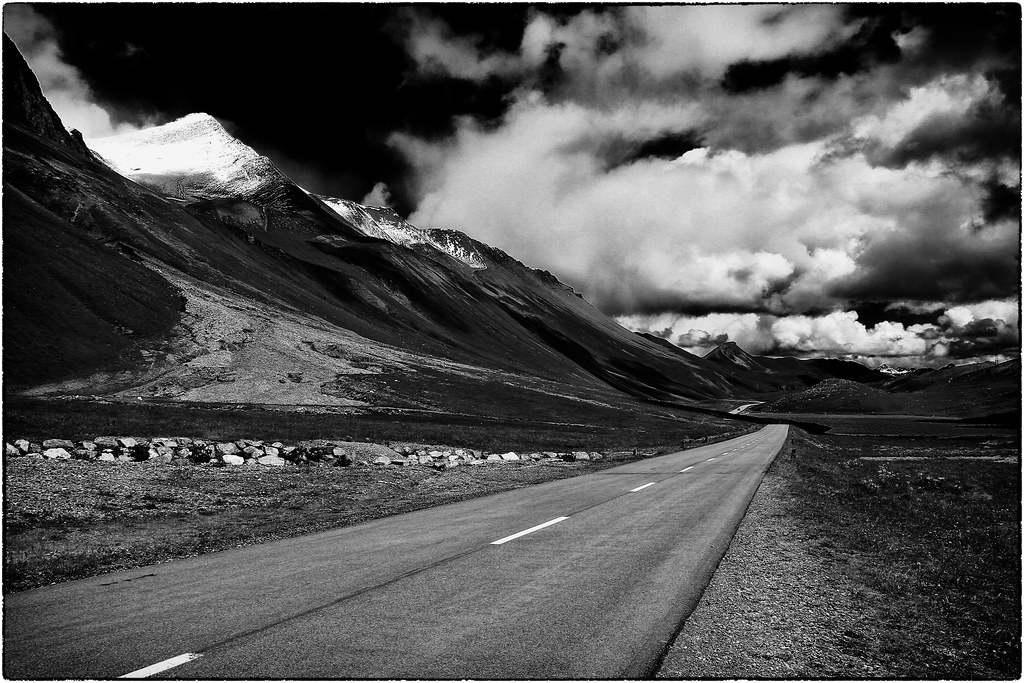

It is a long journey. It always has been. And we are still on it together.