Earlier this week, my middle son and I woke up bright and early in order to beat Chicago rush hour traffic and make it to Champaign, Illinois in time for his orientation/registration day. While our older son is also a student at U of I, the new student process then was entirely online because of the pandemic. So this was a new experience.

Having grown up in another Big Ten college town (Ann Arbor) and spent much of my career in higher education, there was something reassuringly familiar about walking on the sleepy quad in the summer, entering the student Union building, and witnessing the beautifully diverse array of students and families on hand. At a time when universities have become sites of so much contention, this was a visceral reminder of their incredible positive possibilities.

[Related side note: Last year I published an article in the Shalom Hartman Institute’s journal, Sources, entitled, “American Jews & Our Universities: Back to Basics.” I’m pleased to share that it was recognized as the runner-up in the Excellence in North American Jewish History category of the Simon Rockower Awards for Excellence in Jewish Journalism. Shout-out in particular to the journal editor, my old college friend Dr. Claire Sufrin, for her excellent guidance.]

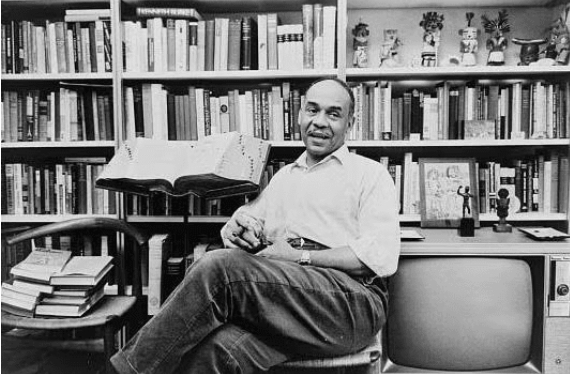

After a morning of the expected sessions (how to pay your bill, how to use the health center, getting oriented to your department/school), my son eventually went to register for courses. I waited in the campus bookstore (always on brand). As I perused the shelves, I came across a copy of “The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison.” This was a delight, as Ellison is someone I’ve always wanted to read more of but for whatever reason have never gotten around to. I wasn’t disappointed.

For starters, I discovered that we shared some common interests: He too had studied music before embarking on a career as a writer and academic. Additionally—and perhaps related, or maybe not—Ellison and I share a preoccupation with questions about the nature of the American experiment, particularly the experiences of the minority groups with which we each respectively identify, while simultaneously claiming and holding fast to the label “American.”

In 1970 Ellison published an essay in Time magazine entitled, “What America Would Be Like Without Blacks.” He observes that one of the enormous contributions of African-American culture to American life in general has been “to remind us that the world is ever unexplored, and that while complete mastery of life is mere illusion, the real secret of the game is to make life swing.” (The musician in me thrills to that metaphor.) Imagining an American history without African-Americans—an idea he dismisses as objectionable on both ideological and pragmatic grounds—Ellison observes that such a history would yield the absence of a “tragic knowledge which we try ceaselessly to evade: that the true subject of democracy is not simply material well-being, but the extension of the democratic process in the direction of perfecting itself.” And then he adds, “The most obvious test and clue to that perfection is the inclusion, not assimilation, of the black [sic] man.”

|

There is much to say: About the meaning of democracy as including, but not limited to, material well-being; about the essential energy of American democracy as aimed at an ongoing, asymptotic quest to perfect itself as it expands to represent everyone it serves, ever more fully; about the striking resonance of Ellison’s notion of inclusion without assimilation with the experience of Jews—in America and, really, every place. (It’s also striking that the preface to this edition of Ellison’s essays was written by Saul Bellow, who, recalling a summer he and Ellison shared a rental house in Dutchess County, comments on some similar motions in the stories of African-Americans and American Jews.) I’m writing all of this, first and foremost of course, because it’s July 4. We could leave it at that and it would be fine. But these reflections are also meant to explore connections between our lived experience and our never-ending exploration of the Torah. Which brings us to our Torah portion, Chukat, and particularly its very last line: “The Israelites marched on and encamped in the steppes of Moab, across the Jordan from Jericho” (Num. 22:1). The people have just come through several encounters with foreign nations, including military victories. They have taken possession of land on the eastern side of the Jordan, and they will stay there until the end of the Torah. This last sentence frames several events to come in next week’s Torah portion, including Balak’s engagement of Balaam to curse the people, and the violent episode involving the sexual/marital relationships between the Israelites and Midianites. Which is all to say that one of the animating questions of this entire section of the Torah is something like this: What does it mean to be an Israelite? How, if at all, can others join this group? How does the people relate to the other peoples around it—and how do those peoples relate to them? These are bigger questions than this space allows for. But by way of conclusion, I want to bring in a teaching of Rabbi Menachem Nachum of Chernobyl, the starting point of which is a verse from earlier in Chukat (Num. 15:14). Here’s what he says: “There are 600,000 letters in the Torah, against which there are also 600,000 root-souls… Therefore, each Jew is connected to one letter in the Torah… Each letter represents the divine element in each person. It is actually the very letter from which their soul derives. It is this letter that pours forth divine blessings and holy vital force.” What is so significant about this teaching to me is the notion that every one of us has a place in the Torah—a spiritual heritage, a home in the universe, despite even millennia of diasporic existence. That sense of spiritual groundedness is essential to any further discussion of political at-homeness—for Jews or anyone else. Perhaps the great American jurist Learned Hand put it best, in his short but essential speech from 1944: “Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can even do much to help it. While it lies there it needs no constitution, no law, no court to save it.” As I have written before, I believe our spiritual practices are what Tocqueville had in mind when he wrote about the “habits of the heart” essential to democratic life. We claim our spiritual inheritance, we live lives of Torah, in order to be both fully ourselves and fully human. That is the ground from which flows the rest of our lives, as individuals, as communities, as nations, and as humanity. May we renew ourselves in that practice, and help every image of God to find their place in the family of things. Shabbat shalom, and a meaningful Independence Day to all who observe. |