A Prayer for Peace

By Rabbi Nancy Flam

“It’s hard to be a person.” That’s what my best friend from college says sometimes to console me when I’m having a tough time. I can’t hear those words without my heart softening. It is hard to be a person. And if the truth of that isn’t piercingly clear for you or me personally in this very moment, odds are it will be.

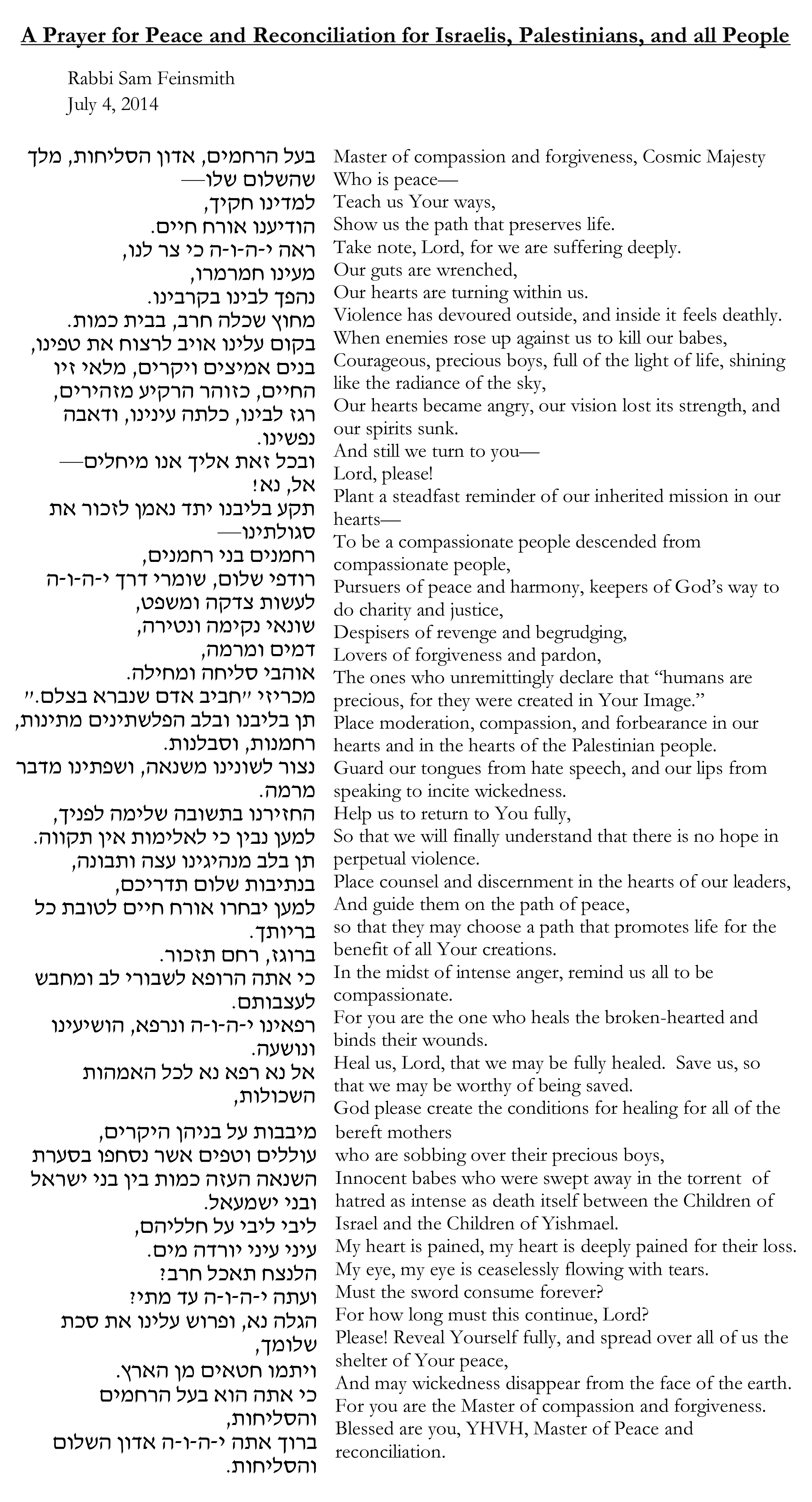

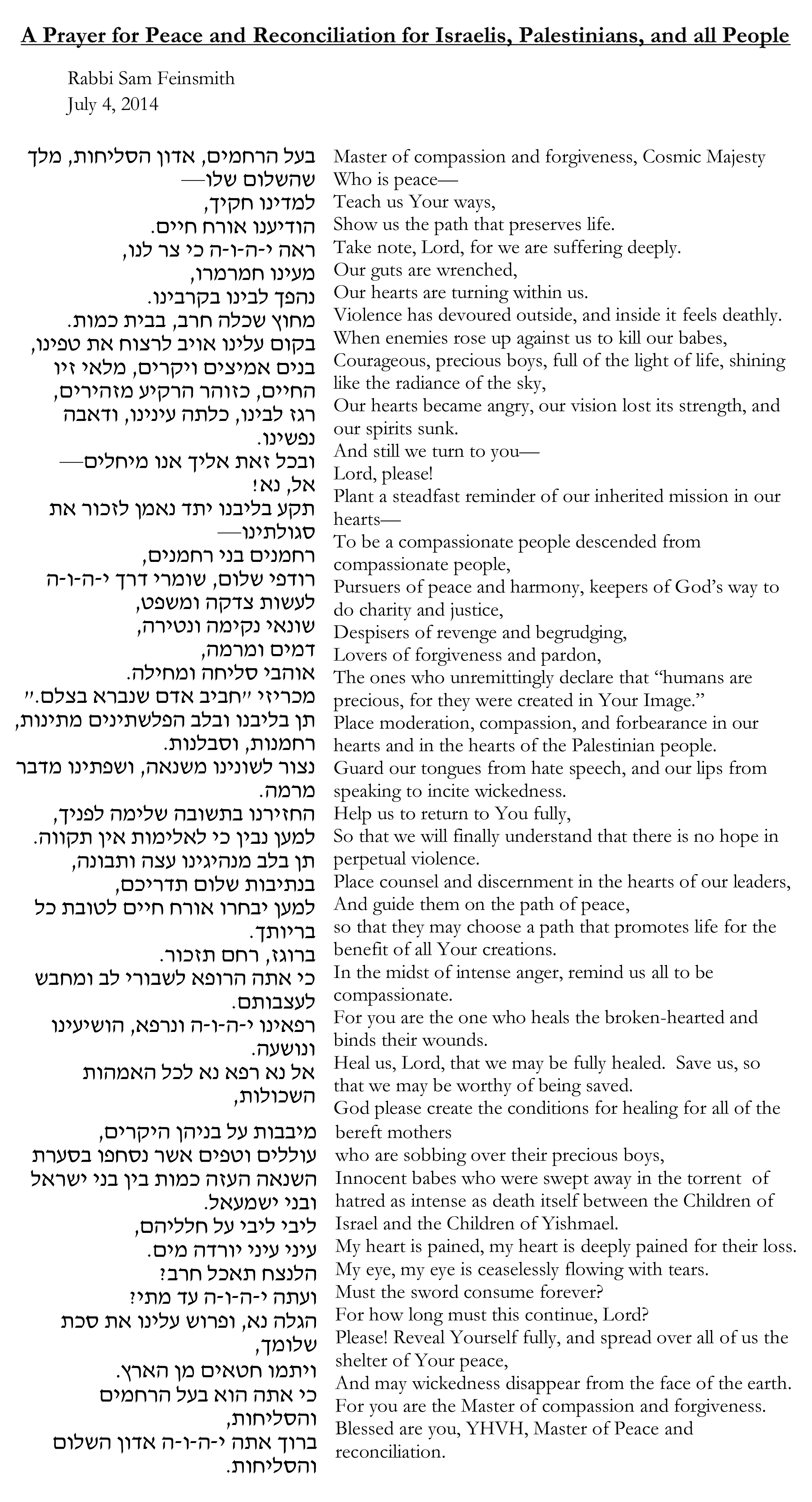

Today my friend Amy and I studied a couple of small pieces of Torah in the Hasidic collection, Itturei Torah (Volume 3, page 268) on the verse describing how God passed before Moses and declared God’s essential attributes (known as the Thirteen Attributes – Shelosh Esray Middot; Ex. 34: 6 – 7). About this verse Rabbi Yochanan is quoted in the Talmud as saying: “God said to Moses, ‘Every time that Israel sins, they will perform (literally: do) before me this seder (literally: order), and I will forgive them.’” The recitation of this seder – this liturgy- of the Thirteen Attributes assumed a central place in the yearly Jewish ritual enactment of forgiveness that takes place over the Days of Awe, beginning on the Saturday night before the New Year at the Selichot (“Forgiveness”) service. We Jews do indeed come before God with these very words, this seder tefillah, this liturgy of the Thirteen Attributes, and we plaintively recite them. We are comforted in knowing that, according to the rabbis, God cannot hear these words without compassion arising, without showing forgiveness. It’s as if God hears these words and softens, remembering with kindness: It’s hard to be a person.

The first small piece of Torah we studied by Alschich (1521 – 1593, Tzefat) pointed out that if one reads the Talmud text carefully one will notice that Rabbi Yochanan said that God instructed Israel to do (ya’asu) this seder before God, not say (yomru) it. Evidently, it’s not enough that we say these words to effect forgiveness. We have to enact these qualities that are attributed to God in our own lives (imitatio dei). We have to do them – to manifest them, to become them – and not just say them. That’s the work that is truly transformative. Perhaps Rabbi Yochanan’s teaching was directed to Jews in his own time who were relying too much on the ritual recitation of words alone, thinking that they would be sufficient to effect transformation, and weren’t working on themselves, cultivating day by day and challenging moment by challenging moment these essential qualities of compassion, kindness, patience and forbearance. They turned away from the hard work of being a person.

And then the second (unnamed) teacher in the anthology of comments on Rabbi Yochanan’s instruction regarding the Thirteen Attributes notes that we are told to do them “k’seder hazeh” which literally means “in this order”. Our teacher explains that this means “one should start with the first attribute: compassionate and gracious. [And as the rabbis have taught elsewhere,] just as God is compassionate and gracious, so should you be compassionate and gracious.” So, we are to “do” or make these attributes, not just say them. We are to become them in imitation of God. And furthermore, in this order: “Start with compassion. Don’t start at the end of the list: not remitting punishment, but visiting the iniquity of parents upon children and children’s children…”

I don’t know who gasped first. After a very long silence in which our minds each turned to the possibility of escalating violence, of acts of vengeance, of actions that could create harm for generations, one of us said something like, “Oh my God.” In this heartbreaking time in Israel and Palestine, Torah spoke with unmistakable clarity: Don’t start at the end of the list. Start with compassion. (The end might just then disappear.)

Rabbi Aryeh Ben David

Founder and Director of Ayeka: Center for Soulful Education

I felt like a shattered piece of glass. Intact, but splintered into thousands of pieces.

It was the moment of emerging from my first mikveh experience. Over 30 years ago, and still etched into my memory.

Broken and intact. Reconfiguring, changed. Putting myself back together into a new permutation. Renewed.

Immersion is easy to do in a mikveh. Full connection is the key to purification. I was naked vulnerability. I was open to allowing my life to fracture and be rearranged. I was full of dreams of a new and more pure version of myself.

How can we bring this model of immersion, purification, and renewal into a learning environment? How can we fully ‘dip’ into the waters of Torah? How can we bring nakedness and vulnerability into an ostensibly mind-centered activity?

I would like to propose a simple 4-step process that can offer us an immersion in our learning and teaching:

1. Listening

2. Talking

3. Talking

4. Listening

Step 1: I listen.

I listen for a line or section in the source that deeply resonates within me. I am open and exposed in front of the text. I allow the words to flow over me. What line was written just for me, for right now? I may have to read the text again and again. There are many who have a custom of dipping in the mikveh 7 times. Sometimes we need to immerse ourselves again and again until we are purified; sometimes we need to immerse in the texts again and again until they penetrate through our skin. I don’t proceed until something in the learning has touched my inner self.

Step 2: God talks.

I imagine God talking to me through the chosen text. What is God saying to me through these words? The text is an invitation to listen to God’s voice. It is not the water that purifies – water is the messenger from the heavens to connect me to something beyond. So too these holy words – they are messengers from heaven to connect me to God. What is God conveying to me, right now? What message do I need to hear?

Step 3: I talk.

God has opened the conversation. Now I respond. I open my mouth and talk openly about where I am and what I need to move closer to God, to live more in the Image of God. I don’t think it or reflect on it – I need to talk it aloud.

I see my fractured life and accept it. I verbalize what I am struggling with and how these verses address my situation. I articulate how these verses can heal and purify me. I bless and thank God for the opportunity to grow.

Step 4: God listens.

After talking, I sit with myself for a few moments. The early masters would sit for a few moments after praying, being with the moment. The ‘being’ allows for the broken pieces to reconfigure and reunite. It is a healing moment of being. I am emerging from the mikveh of my learning and am now becoming a new version of myself. Only God can rearrange the pieces. Only God can purify. The mikveh is a birthing process. I am pure because I am no longer stuck in my former self. I have transformed into a new self. This is the mikveh of learning – of being with my new self, of affirming that I can perpetually transform myself to become closer to God.

Open, naked, vulnerable, and seeking a personal connection with the Beyond. These are the prerequisites for full immersion – in a mikveh or in a learning setting.

Rabbi Jonathan Slater

It is a delight and an honor to be able to bring these translations of some of R. Levi Yitzhak’s teachings out into the world, and to connect them to our own lived lives. I have tried to be concrete in suggesting how these teachings can be practiced daily, how they can be brought into our day-to-day experience. Here is an example for Shavuot:

We are taught in the Talmud (Pesachim 68b): R. Eliezer said: “On a Festival we have no other option than either to eat and drink or to sit and study”. R. Yehoshua said: “Divide it: half of it to eating and drinking, and half of it to study. In response R. Yohanan said: “Both come to their teaching from the same verses. One verse says, ‘[After eating unleavened bread six days, on the seventh day] you shall hold a solemn gathering (atzeret) for YHVH your God: [you shall do no work]’ (Deut. 16:8), while another verse says, ‘On the eighth day you shall hold a solemn gathering (atzeret); [you shall not work at your occupations]’ (Num. 29:35). R. Eliezer reasons that the atzeret is either entirely for God or entirely for you, while R. Yehoshua reasons that we divide it, half for God and half for yourselves.” … R. Eleazar said: “All agree in respect to Shavuot (called atzeret by the Sages) must be ‘for you’ too. What is the reason? It is the day on which the Torah was given.”

On Pesach we rejoice; we rejoice in our bodies that we have come out from slavery. This is a physical boon. On Shavuot the joy is because God gave us the Torah. But, receiving the Torah is only a spiritual joy, and it is difficult for the body to rejoice.

That is why the Sages taught that Atzeret must be also “for yourselves,” so that the body, too, will rejoice. In this way we will truly believe that Torah offers us two lives (chayyei olam): the life of the world to come and the life of this world. Scripture proves this: regarding the former it says, “In her right hand is length of days, [in her left, riches and honor]” (Prov. 3:16); regarding the latter, “It will be a cure for your body, [a tonic for your bones]” (ibid. 8). Therefore, the body will rejoice as well, exulting from bringing this awareness to heart.

Other Festivals are endowed with specific rituals to mark their observance. But, this is not the case with Shavuot. Therefore, the sages emphasize that it, too, is meant as a day in which we take delight, and is not only one of spiritual devotion. This is an invitation to Levi Yitzhak to emphasize the Hasidic attention to the body as a potential source of spiritual awareness. We come to perceive the presence of the divine not by withdrawing from the world, but by bringing even more focused and precise attention to it. It is there that we will come to know that all of creation is filled with God’s glory.

Levi Yitzhak is aware of this as well. He notes that when we experience delight in the body, it helps us to connect to our spiritual selves. Those activities that we find liberating – those that we choose, those that enliven the body, those that delight the body – free the heart and mind and soul to reach out to God in celebration and thanks. Those activities that we experience as limiting or burdensome, dull the spirit and bring darkness.

Perhaps, then, we might want to ask what is missing in our engagement in synagogue services. How might they be like “Shavuot” in this lesson: activities that are cerebral, where the meaning is an idea and experience ephemeral? If this analogy is to be helpful, then something like “food and drink” to engage and delight the body may be needed to enliven the experience, and turn it into a delight.

Here are a few suggestions for investigation:

Fatigue and boredom are the products of dissociation and alienation. Connecting again to our own inner experience – both of the spirit and of the body – can help to bring delight into our communal religious lives.

When I was a little girl, my mother taught my brothers and me to make chains of colored construction paper, one loop for each day before a longed-for event. Each evening before going to bed, we would ceremonially tear one loop off the chain and know how many days were left. In the spring we counted down to summer vacation; in the fall I counted down to my birthday.

As a people, we are similarly counting down at this time of year. During sefirat ha’omer (the counting of the Omer), each evening for the 49 days following Passover, we ceremonially mark off one more day as we proceed towards the longed-for holiday of Shavuot, the celebration of receiving Torah at Mt Sinai.

When I was a child, the purpose of the counting was to hurry along time as much as possible. It was an answer to the impatient question, “How many days NOW?” But spiritual practice helps us see this process in a very different light. Rabbi Nachman of Breslov taught that we must continually strive to see hasechel sheyesh bechol davar, the intelligence, or even signs of Divinity, that can be found in every single thing. His devoted disciple, Natan Sternharz, also known as Reb Noson, connected this teaching to counting the Omer.

Reb Noson noted that signs of Divinity can be found not just in every item, but in time as well—every day, hour and minute in its own unique way. To an ordinary person dealing with transactions and traffic and responsibilities, it’s a tall order to achieve the constancy of awareness that would permit us to see those unique signs of Divinity every day, let alone every minute! So we have this time of counting to help us practice being more finely attuned to the unique holiness of each particular day. For those of you interested in Mussar, it is very similar to the Mussar world’s offering of kabbalot, small tasks or opportunities to practice a particular middah or characteristic. The counting of the Omer is a bounded, but intensive training period for awareness.

So the counting is not to hurry along time. The counting is there to slow us down, to notice. Today is the 28th day of the Omer. What is unique about it? Where will the holiness be? Where might I find signs of Divinity if I only knew?

Wishing everyone a counting filled with wonder and blessings and joy!

By Rabbi Joshua Levine Grater

My kids are getting older, and with their aging, they are starting to ask questions about time, length of life and death. They understand the concept of being born, as they have cousins who have been born recently, and they understand that life ends, both from their obsession with Harry Potter, which has main characters dying, and from the fact that their dad is often out at night at a shiva minyan. We have had some amazing discussions over this Pesach time, as they now like to sit and “talk like grown-ups,” as they put it—about time, life, memory, and understanding the differences between 100 years ago, like when their great-grandfather was born, 1000 years ago, and 3000 years ago, like when Moses lived. They are still only 9 years old, so of course I reassure them that they have a long and beautiful life ahead of them. And I try not to burden them with my own neuroses about time, my own struggles with understanding and living within the construct that yesterday will never happen again, that each day forward is a day closer to an end that is always fast approaching, but—please God—is hopefully far off in the future.

It is so wonderful to be a child, innocent and free of these mental burdens that can both invigorate and infuriate adults, as we all deal in our own ways with the concept of time and the counting of our days. I remember lying in bed, as my kids say they now do, wondering what it is like to die, how it will be that the world will go on and on, for billions of years, without me? This can either paralyze us into a life of fear, or it can inspire us to a life of meaning. Most of us live somewhere in between. As Dr. Sherwin Nuland writes so beautifully in his landmark book, How We Die, “Against the relentless forces and cycles of nature there can be no lasting victory.” But, with faith, hope, values and meaning, we can achieve a life that will live on beyond us.

We mark occasions of time, both celebratory and painful ones, which serve as guideposts in the sea of a lifetime. 128th birthday of Pasadena, 69th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, bar/bat mitzvah, 13 year anniversary of 9/11 approaching, 66 years of the State of Israel—all important milestones in the life of individuals and nations. Yet, how many of us ever pay attention to the passing of each day, I mean really count and mark each day of our lives as important, meaningful, reason for celebration? As we are in the period known as sefirat ha’omer, the counting of the Omer, which counts the days from Pesach to Shavuot, I am thinking about counting our days, and focusing on the meaning of a day in our lives, which is the most concrete block of time that we all share in common.

Biblically, the counting involved the time from the second day of Pesach until Shavuot, 49 days, culminating in the barley harvest and the offerings of the first grains at the Temple. Not being a farmer myself, I don’t know that much about barley, but I do know that it is a very sensitive grain, one that needs to be harvested at a precise moment; if that moment passes, the barley dies and the crop is lost. Hence, the counting of each day with great care and attention. Today, however, we are not harvesting any wheat or barley, and we don’t have the Temple, so why count? Where do we find meaning in this ritual? I want to suggest a few options.

Our lives are like the barley, sensitive and in need of great attention. Inside the tough, outer shell of the human body, our souls and spirits require love and devotion, a constant dedication of commitment to maintain a healthy life. We tend to focus on the body, exercising and eating right, getting enough sleep, taking vitamins and seeing the doctor. Yet, how many of us pay the same amount of attention, give the same amount of time and energy to our souls? Sefirat ha’omer offers us the chance to spend 49 days in direct contact with our souls on a daily basis, for each day that we count, we focus on a different aspect of our inner being.

Coming out of Mitzrayim (Egypt), we left the place of limitations and boundaries, a place that represents all forms of conformity and definition that restrain, inhibit or hamper our free movement and expression. Therefore, leaving Egypt is about embracing freedom from constraints. (Rabbi Simon Jacobson) The Omer invites us to count each day as a single unit of time, a unique period in our life that happens only once. What did today mean for you? Were you compassionate, disciplined, productive? Did you study, spend time doing something solely for yourself? Did you love someone today? Did you love yourself?

Each day has infinite value, infinite worth, infinite potential. We often overlook that idea in favor of greater periods of time: how was my week, my month, my year? Yet, hayom (today) is the most precious gift, for as the old adage goes, “today is a gift, which is why it’s called the present.” When we count each day, we don’t wait for greatness to come tomorrow or next week; when we count each day, we might find out how wonderful or painful, how rich or poor, how glorious or frustrating our lives truly are. If it is the positive, we can celebrate that. If it is the negative, we can recognize it and, hopefully, do something about it before it snowballs into something more major, more harmful.

This period of counting the Omer, these next several weeks, I invite you to tap into the power of life-affirmation through acknowledging time passing; mark the end of each day, before you go to sleep, by reviewing your day, seeing where you succeeded, achieved, produced, laughed, shared, gave, received. And, see where you could have done better, been nicer, kinder, who you may have hurt and who hurt you; ask for forgiveness and offer forgiveness. And then, with the spirit of our people, count the day.

As I have taught my kids, life is precious, each moment matters, the less we take for granted the better. As Shakespeare has Julius Caesar remind us, “Of all the wonders that I yet have heard, it seems most strange to me that men should fear; seeing that death, a necessary end, will come when it will come.” May we all live long, healthy and rich lives, and when that day arrives, when life in this world transitions to the next, may we have counted each of those days of life with as much fullness and fortitude as humanly possible.